The Gilded Age not only witnessed an unprecedented boom in technological advances and the businesses created by a rapidly globalizing economy, but the amazing growth of equally advanced professions within the African-American community. Whether it be the manufacture of hair products and beauty schools, the opening of colleges and universities, or the founding of a life insurance company, African-Americans defied commonly-held assumptions about their intelligence, work ethic, and ingenuity—particularly within less than fifty years after emancipation.

The Gilded Age not only witnessed an unprecedented boom in technological advances and the businesses created by a rapidly globalizing economy, but the amazing growth of equally advanced professions within the African-American community. Whether it be the manufacture of hair products and beauty schools, the opening of colleges and universities, or the founding of a life insurance company, African-Americans defied commonly-held assumptions about their intelligence, work ethic, and ingenuity—particularly within less than fifty years after emancipation.

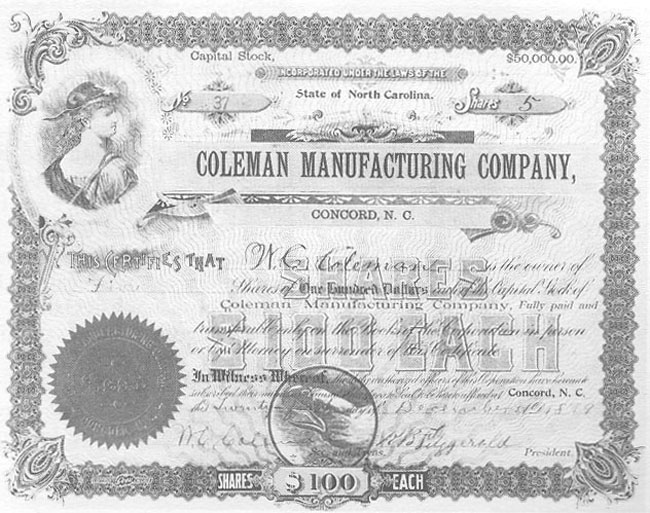

A definite stroke of shrewdness was the establishment of Coleman Manufacturing Company, which was formed in Concord, North Carolina in 1897 as the first and only cotton mill owned and operated entirely by blacks. Under slavery, blacks had been the primary source of labor for the cotton industry, but after the collapse of slavery and Reconstruction, and the sharp rise in immigration, cotton mills of the “New South” began to turn to cheap immigrant labor to the near exclusion of black hands. African-Americans continued to labor in cotton fields—mostly as sharecroppers—but the more lucrative positions in factories eluded their grasp, particularly when immigrants began to emulate the attitudes towards blacks held by their poor white co-workers and refused to work with and alongside black factory workers. With these barriers in mind, North Carolina businessman Warren C. Coleman exhorted with fellow black Southerners to support his plan to build a cotton mill owned, operated, and run strictly by blacks:

Please allow me to call the attention of the public to the fact that a movement is on foot to erect a cotton mill at Concord to be operated by colored labor. The colored citizens of the United States have had no opportunity to utilize their talents along this line. Since North Carolina has fairly and justly won for herself in the Centennial at the World Fair at Chicago and at the Atlanta Exposition the honored name of being “the foremost of the States,” she will further evidence the fact if she is the first to have a cotton mill to be operated principally by the colored people. We are proud of the spirit and energy of the white people in encouraging and assisting the enterprise and will our colored people not catch the spark of the new industrial life and take advantage of this unprecedented opportunity to engage in the enterprise that will prove to the world our ability as operatives in the mills thereby solving the great problem “can the Negroes be employed in cotton mills to any advantage”? And now that the opportunity is before us, experience alone will determine the question and it behooves us to better ourselves and do something, and as one man . . . [make] the effort that is to win for us a name and place us before the world as industrious and enterprising citizens…

Read more here

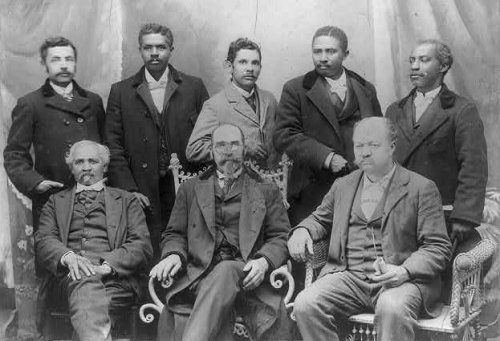

Coleman Manufacturing Company was incorporated in mid-1897 with an initial stock outlay of $50,000, which rose to $100,000 with the subscriptions of other African-Americans living in or near Concord, and a number of white businessmen, including Tobacco king, Benjamin Duke, who subscribed $1,000 at six-percent interest. On February 8, 1898, the cornerstone of the 80×120 feet three-story brick building which would house Coleman Cotton Mill was laid, and following the election of officers, R. B. Fitzgerald was appointed President; E. A. Johnson, vice-president, and W. C. Coleman, secretary and treasurer, whilst the Rev. S. C. Thompson; L. P. Berry; John C. Dancy; Prof. S. B. Pride; Prof. C. F. Meserve; and Robert McRae constituted the board of directors.

Coleman Manufacturing Company was incorporated in mid-1897 with an initial stock outlay of $50,000, which rose to $100,000 with the subscriptions of other African-Americans living in or near Concord, and a number of white businessmen, including Tobacco king, Benjamin Duke, who subscribed $1,000 at six-percent interest. On February 8, 1898, the cornerstone of the 80×120 feet three-story brick building which would house Coleman Cotton Mill was laid, and following the election of officers, R. B. Fitzgerald was appointed President; E. A. Johnson, vice-president, and W. C. Coleman, secretary and treasurer, whilst the Rev. S. C. Thompson; L. P. Berry; John C. Dancy; Prof. S. B. Pride; Prof. C. F. Meserve; and Robert McRae constituted the board of directors.

According to Evidences of Progress Among Colored People:

The mill is to have from 7,000 to 10,000 spindles, and from 100 to 250 looms, and, by their charter, will be allowed to spin, weave, manufacture, finish, and sell warps, yarns, cloth, prints, or other fabrics made of cotton, wool, or other material. They own at present, in connection with the plant, about 100 acres of land on the main line of the Southern Railway, and near the site of the mill. The mill and machinery with all the fixtures complete will represent an outlay of nearly $66,000, and will give employment to a number of hands.

It seemed as though all the world was watching this unique enterprise, but though four-room mill houses were built in 1900 and the mill was held up as an example of African-American progress at the Negro Exhibit during Paris’ Exposition that same year, Coleman Manufacturing ran into a bevy of problems stemming from the initial purchase of second-hand English machinery, Coleman’s inability to raise enough cash to pay his workers (who were initially paid in company stock), and the high price of cotton. Coleman was able to inform investor Washington Duke of the company turning a profit in 1901, the financial problems were too great to solve and the mill closed temporarily in 1902. By the following year, Coleman was forced by economic pressures to turn the mill over to a local white cotton merchant, who promptly hired white workers at the mill. Unfortunately, by then the mill was a total bust and Coleman’s unexpected death in 1904 hastened the closure of the cotton mill, which had appeared to be a bright beacon of hope to African-Americans and white investors/philanthropists in 1897. Despite the rapid rise and fall of Coleman Manufacturing Company, it continues to stand as a definite nod to the achievements and abilities of African-Americans at the turn of the century, who refused to believe they were barred from the fruits of the Gilded Age.

It seemed as though all the world was watching this unique enterprise, but though four-room mill houses were built in 1900 and the mill was held up as an example of African-American progress at the Negro Exhibit during Paris’ Exposition that same year, Coleman Manufacturing ran into a bevy of problems stemming from the initial purchase of second-hand English machinery, Coleman’s inability to raise enough cash to pay his workers (who were initially paid in company stock), and the high price of cotton. Coleman was able to inform investor Washington Duke of the company turning a profit in 1901, the financial problems were too great to solve and the mill closed temporarily in 1902. By the following year, Coleman was forced by economic pressures to turn the mill over to a local white cotton merchant, who promptly hired white workers at the mill. Unfortunately, by then the mill was a total bust and Coleman’s unexpected death in 1904 hastened the closure of the cotton mill, which had appeared to be a bright beacon of hope to African-Americans and white investors/philanthropists in 1897. Despite the rapid rise and fall of Coleman Manufacturing Company, it continues to stand as a definite nod to the achievements and abilities of African-Americans at the turn of the century, who refused to believe they were barred from the fruits of the Gilded Age.

Further Reading:

Evidences of Progress Among Colored People by G. F. Richings

From the Cotton Field to the Cotton Mill by Holland Thompson

Proceedings of the National Negro Business League (first meeting) by National Negro Business League

This is a really interesting period. I’m glad to find your blog (at Historical Tapestry). I live in Hoboken, NJ, which is filled with factory leftovers from this time period, some in better shape than others, and I often wonder what stories they hold.

Thanks for stopping by Melissa! And I too wonder about abandoned buildings. On a recent road trip about thirty miles north of my city, I ran into a few acres of abandoned wheat mills, and it was both eerie and fascinating to think about how utterly decayed and dead a once-thriving area had been.