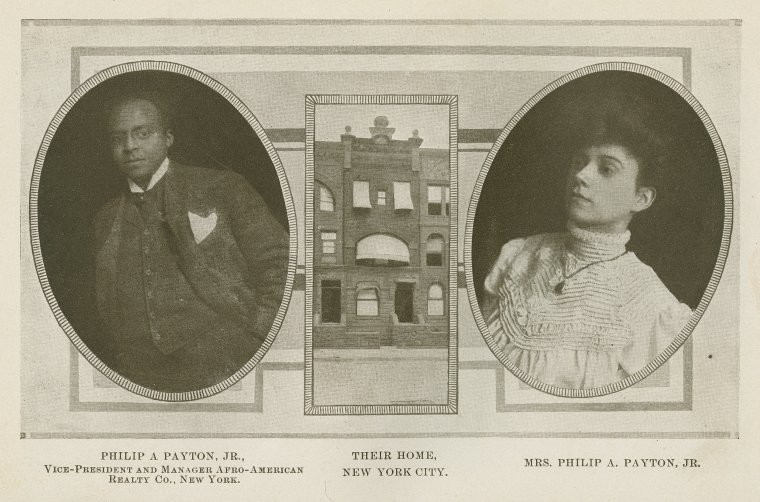

Phillip A. Payton, Jr. (1867-1917) and his Afro-American Realty Company took advantage of the real estate “color line” in New York and helped to establish Harlem as a major cultural landmark in African-American history. Born the son of a tea merchant and barber in Westfield, Massachusetts, Payton moved to New York soon after graduating from Livingston College and took odd jobs such as department store attendant and barber, to support himself and wife, Maggie. While working as a janitor for a real estate company, Payton grew intrigued by the profession and decided to enter the business himself. He must have certainly felt the winds of change, because turn of the century New York was a destination for a significant number of black Southerners migrating to the better and higher paying jobs, and more tolerant racial climate of Northern cities. These migrants found a better clime than the South, but New York’s black citizens remained marginalized by the real estate industry, which confined them to dilapidated pockets of the city such as San Juan Hill or The Tenderloin, where they typically paid higher rents than their non-black neighbors.

Even more frustrating was the rejection of black tenants from renting or purchasing in the up-to-date neighborhoods being built in Upper Manhattan, including Harlem, which had transformed from a quiet, largely middle-class area to an extremely fashionable area for the well-to-do. Harlem of the 1890s was filled with brand-new, very modern townhouses and high-class apartments, and the real estate boom caused most to inflate the costs of these homes in hopes of turning over large profits. When the housing market collapsed in 1904, landlords were left with expensive buildings and no tenants willing to pay the high rents. However, the growing African-American community, which also included a growing wealthy middle-class, hungered for better housing, and Payton’s real estate company stepped in to fulfill this desire.

After many failures, which found Payton and his wife temporarily homeless, he then won his reputation when a wealthy white realtor conspired to eject black tenants from their homes on West 135th Street, with the object of filling the houses with white tenants and charging higher rents. Payton formed the Afro-American Realty Company to fight this tactic and other methods of pushing well-to-do blacks out of good neighborhoods, and he earned the admiration (and attention) not only of middle-class African-Americans, but of sympathetic white investors and real estate agents. Using his network of realtors and bankers, as well as influential African-Americans, Payton’s realty company began to acquire five-year leases of the Harlem homes (which landlords were eager to fill) and rented them to black tenants. By 1907, the company had obtained control of twenty new York apartment houses, valued at $690,000, and the capital stock of the company was $500,000, of which about $135,000 had been paid in. Payton used his platform to promote black-owned enterprises in New York and other cities, and organized a local black defense society to protest police brutality. He also drew together a group of black real estate agents and other businessmen, including John M. Royall, John E. Nail, and Henry C. Parker, all of whom had adapted Payton’s methods to advance black expansion in Harlem, even as his fortunes began to decline around 1908.

The Afro-American Realty Company’s success was shaken up by stockholders who doubted Payton’s high-risk speculations and his autocratic style of managing the company. In 1906, stockholders sued Payton on the grounds that he ran the company without any input from the board of directors, which made him responsible for any losses the company might accrue. Payton was also sued for fraud, since, while he claimed the company owned its properties, all were heavily mortgaged. The courts cleared Payton of any wrongdoing, but found the Afro-American Realty Company guilt of misrepresentation, and though it remained afloat for another two years, the bad press created by the lawsuit and Payton’s own speculations made obtaining credit increasingly difficult. The company failed in 1908, though other black realtors continued using Payton’s revolutionary methods of promotion and expansion. Payton formed Philip A. Payton Jr. Company that year and continued to keep his hand in the world of Harlem real estate, and in 1917, he made the biggest deal of his career when he purchased six apartment buildings valued at $1.5 million. Before he could even bask in the fruits of his labor, he died of illness in his summer home in Allenhurst, New Jersey that August.

Because of his role in opening Harlem up to African-Americans, Payton was christened the “Father of Colored Harlem.” Soon after his death, the legacy of the Afro-American Realty Company reached fruition, with the growth of Harlem into a “black mecca,” which reached its full glory during the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s. According to Ephemeral New York, Payton’s New York home, 13 West 131st Street, still stands.

Further Reading:

The Negro in Business by Booker T. Washington

Harlem Renaissance lives from the African American national biography by Henry Louis Gates

Thanks for this post. I have lived in Hamilton Heights aka Harlem, but I never knew about Philip Payton until I took a walking tour of the neighborhood. My grandparents used to own a house on Hamilton Terrace, which they would never have been able to own if it hadn’t been for Payton’s pioneering company.

You’re welcome Elizabeth. And thank you for your wonderful ancedotes–I am forever thrilled when you stop by with something extra to contribute to the topic.

Wow-what a fascinating story! Thanks for sharing it!

Blessings,

Kim

You’re welcome, Kim!