In pursuit of beauty, women of all ages and from all walks of life have created a demand for products in which to enhance what God gave them, to conceal what they wish He didn’t give them, and create what they wanted God to give them. As such, the beauty industry was created despite appeals for “natural” beauty and admonishments that ladies didn’t rouge or powder, nor did they wear anything heavier than lavender or rose-water. The fact that the modern beauty industry laid its foundations in the so-called “repressed” Victorian era tells otherwise.

In pursuit of beauty, women of all ages and from all walks of life have created a demand for products in which to enhance what God gave them, to conceal what they wish He didn’t give them, and create what they wanted God to give them. As such, the beauty industry was created despite appeals for “natural” beauty and admonishments that ladies didn’t rouge or powder, nor did they wear anything heavier than lavender or rose-water. The fact that the modern beauty industry laid its foundations in the so-called “repressed” Victorian era tells otherwise.

The modern perfume industry came into being in Paris between the years 1889 and 1921, with the introduction of synthetic fragrances. Prior to this development, perfumers relied heavily upon natural scents, which could be difficult to obtain, such as with vanilla, ambergris, civet, or benzoin; or to extract its essences, such as with freesia, lilac, violet, or orchid. From the natural distillation of fragrances, the chemical developments of the 19th century culminated in a new perfume industry, based around the combination of natural and synthetic fragrances.

The first synthetic fragrance was the essence of Mirbane introduced by Collas in about 1850. Soon after, came the creation of artificial oil of wintergreen and of bitter almonds in 1868; the creation of coumarin, a chemical compound found naturally in lavender, clover, and tonka beans, that was designed to replicate the scent of freshly mowed hay, by Sir W. H. Perkin that same year; vanillin, which as the crystalline component, was first isolated from vanilla pods in 1858, but was obtained from the glycosides of pine tree sap in 1875, and temporarily caused an economic depression in the natural vanilla industry; and of ionone, almost identical with the natural irone, the odorous principle of violets, by Tiemann and P. Kruger in 1898. In 1888 the chemist Alfred Baur discovered the “artificial musks,” Musk Baur, and secondly, Musk Ketone in 1894, which was widely used until the 1990s because its production was easy and cheap.

From 1887 to 1915, Schimmel & Co, one of the major suppliers of essential oils at the turn of the century, made twice yearly reports on the fluctuations in the supply of natural ingredients as territories were colonized and recolonized and their resources exploited. Gradually, in reaction to the instability of access to natural resources, more and more perfumers turned to synthetic fragrances and Schimmel’s catalogues reflected this. 1895 saw the report of the first synthetic jasmine, and synthetic rose, neroli and ylang-ylang (despite its relative inexpensiveness) followed. Artificial rose oil, was especially touted for its ease of use. It would not “become cloudy in the cold, or separate into flakes. It could be relied upon to be always of exactly the same composition.”

Ironically, the synthetic fragrance became an oxymoron: they were cheap, but colorless in every way. The chemical make-up of an essence had been cracked, but in its creation, the complexity and nuance of a natural fragrance was lost. But that didn’t deter perfumers from both blending the synthetic with the natural  and capitalizing on the brusque, one-dimensional quality of the synthetic (Chanel No 5, created accidentally, is a good example of the latter).

and capitalizing on the brusque, one-dimensional quality of the synthetic (Chanel No 5, created accidentally, is a good example of the latter).

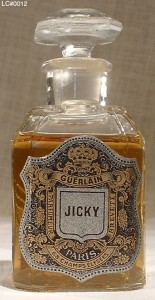

One of the first perfumers to use a synthetic fragrance was Houbigant, whose Fougère Royale,or Royal Fern, was built around an “accord of oakmoss, geranium, bergamot … and synthetic coumarin” in 1882. However, this fragrance quickly vanished from the scene, and the House of Guerlain is frequently cited as creating the modern perfume industry with the creation of Jicky in 1889. A fougère, or fern fragrance, also based around coumarin, it included bois de rose, vanillin, lemon, bergamot, lavender, mint, verbena, and sweet marjoram, with civet as a fixative.

“When it first appeared, many women did not accept or understand it. The hint of animal scent was too brutal and unexpected for women in 1889. In fact, men were the first to appreciate it, and it wasn’t until 1912 that women’s magazines finally began to sing its praises. The perfume bottle is inspired by medicine jars but with a surprising ‘champagne bottle stopper’, symbolizing joy and celebration.”

The House of Guerlain quickly followed which such fragrances as Au bon Vieux Temps (1890), Belle Epoque (1892), Après L’Ondée (1906) and L’Heure Bleue (1912).

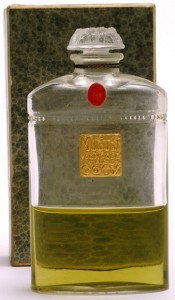

A rival was found in François Coty, who completed the birth of the modern perfume age with his revolutionary packaging techniques. Obsessed with the idea of creating fragrances and presenting them in the perfect bottle, Coty moved to Grasse, the capital of perfumery, where he entered the school of fragrance run the House of Chiris, one of the largest producers of floral essences. Returning to Paris a year later, he met with rejection until, in 1904, after a flamboyant demonstration, Coty got an order for twelve bottles of his latest creation, La Rose Jacqueminot, from the Grands Magasins du Louvres, a major Parisian department store.

In 1908, he opened an elegant shop on the Place Vendôme, which was next door to René Lalique, the great art nouveau jeweler. Asked to design Coty’s perfume bottles, Lalique was able to mass produce them with iron molds. Selling perfume in uniquely designed bottles was revolutionary enough, but Coty dared to allow customers to sample the perfume before purchasing it! Designed by Lalique, small perfume bottles (testers), signs and labels were produced to encourage ladies to try a dab of Ambre Antique or Le Muguet.

In 1908, he opened an elegant shop on the Place Vendôme, which was next door to René Lalique, the great art nouveau jeweler. Asked to design Coty’s perfume bottles, Lalique was able to mass produce them with iron molds. Selling perfume in uniquely designed bottles was revolutionary enough, but Coty dared to allow customers to sample the perfume before purchasing it! Designed by Lalique, small perfume bottles (testers), signs and labels were produced to encourage ladies to try a dab of Ambre Antique or Le Muguet.

As he did with many trends in the years leading up to the Great War, Paul Poiret was the first couturier to create perfumes under his fashion label. In 1911, he set up two companies, one for each of his daughters. For Martine, the youngest, he established Les Ateliers de Martine. For Rosine, the eldest, he established Parfums de Rosine. With packaging designed by Erté, Raul Duffy and Paul Iribe, his fragrance house was so successful, it was rumored Coty wished to buy him out. His perfumers, Emannuel Bouler, Maurice Shaller and Henri Alméras brought Rosine lasting fame with such fragrances as Borgia, Alladin, and Nuit de Chine, which ventured into new territory, combining Oriental ingredients with intense and heady florals.

Hand in hand with the modern perfume industry were cosmetics. Into this field, women featured heavily. Born into a socially prominent Chicago family, Harriet Hubbard Ayers spent a year in Paris after the 1871 fire, thereafter moving to New York to begin business selling a beauty cream called Recamier. Experiencing much success with this, she began to sell perfumes with names like Dear Heart, Mes Fleurs, and Golden Chance. From this, she emerged to become America’s first beauty columnist and the country’s best-paid, most popular female newspaper journalist.

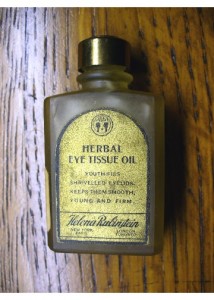

One of the most enduring names in the cosmetics industry is that of Helena Rubinstein. Born in Poland, Rubenstein emigrated to Australia where, with the help of her sister, she began to sell beauty treatments she claimed derived from the Carpathians. Leaving her sister Ceska to assume the Melbourne shop’s operation, Rubenstein moved to London with $100,000 in 1908 to began what was to become an international enterprise.

One of the most enduring names in the cosmetics industry is that of Helena Rubinstein. Born in Poland, Rubenstein emigrated to Australia where, with the help of her sister, she began to sell beauty treatments she claimed derived from the Carpathians. Leaving her sister Ceska to assume the Melbourne shop’s operation, Rubenstein moved to London with $100,000 in 1908 to began what was to become an international enterprise.

Her deadly rival, Elizabeth Arden, founded a North American-based beauty empire. Born Florence Nightingale Graham, Arden traveled to France in 1912 to learn the beauty and facial massage techniques used in the Paris beauty salons. Returning to the States with a collection of rouges and tinted powders she created, she introduced modern eye makeup to North America and the concept of the “makeover” in her salons. With her collaborator, Swanson, a chemist, they created a “fluffy” face cream called Venetian Cream Amoretta, and a corresponding lotion, named Arden Skin Tonic, which revolutionized cosmetics, bringing a scientific approach to formulations.

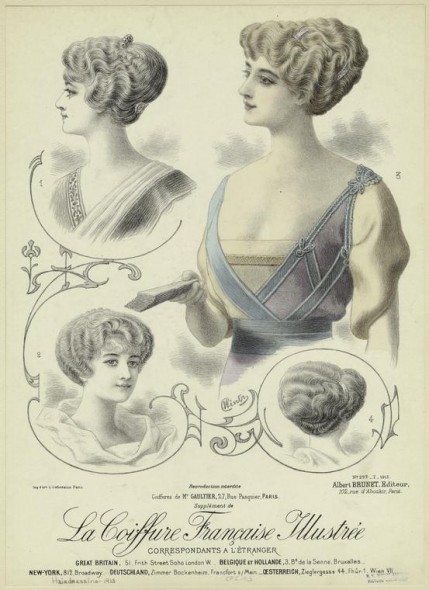

Other beauty inventions included the hair-color formula, developed by chemist Eugene Schueller (the founder of L’Oreal) in 1907, called Auréole; the Marcel wave, a process by which heated tongs were used to curl and wave hair, invented by Francois Marcel, a French hairdresser in 1872; and the Nestle Permanent Hair Wave, created by Charles Nestle in 1906, wherein an electric heat machine was attached to the hair pads protecting the head and curled the hair.

Other beauty inventions included the hair-color formula, developed by chemist Eugene Schueller (the founder of L’Oreal) in 1907, called Auréole; the Marcel wave, a process by which heated tongs were used to curl and wave hair, invented by Francois Marcel, a French hairdresser in 1872; and the Nestle Permanent Hair Wave, created by Charles Nestle in 1906, wherein an electric heat machine was attached to the hair pads protecting the head and curled the hair.

Edwardian ladies also used papier poudre, which came in books of colored paper and were pressed against the cheeks or nose to remove shine, burnt matchsticks to darken eyelashes, and geranium and poppy petals to stain the lips. For those who wished to turn back the hands of time, or at least halt them for a while, many ladies would paint their faces with enamel, thereby “preserving” their beauty beneath a layer of white paint–and it was rumored Queen Alexandra retained her youthful beauty long past the age of sixty with assistance by this process.

A dangerous trend during this period however, was the use of belladonna drops in the eyes. For some reason, it was determined that dilated pupils were attractive to the opposite sex. Interestingly enough, to be beautiful in the Edwardian era was to be brunette–blondes were decidedly out of favor–and cosmetics were created specifically for the brunette, rosy-cheeked woman in mind.

Discreet beauty salons, such as the House of Cyclax, or the more sinister salon run by Madame Rachel (who, despite her infamy, lives on in the eponymous mixture of face power she created for brunettes), lined Bond Street, or near it, where veiled ladies could enter side doors to obtain their face powders and creams, enamels, lip tinctures, and rouges.

But Selfridge’s threw open the doors when it debuted a make-up counter with its opening in 1910, where women could openly purchase cosmetics and even try them on at the counter! This shocked the older generations who stared in disbelief when young women–perhaps even acquaintances–blithely walked up to the counter and professed knowledge of the different cosmetics they wouldn’t have dreamed of admitting they knew. But times were a-changing. By the 1920s, no longer was lily white-skin a sign of breeding: a healthy glowing suntan now professed the wealth and leisure that allowed one to vacation at the beach, and rouging ones knees and powdering ones face, in public naturally, became a common occurrence. The pursuit of beauty was legitimized.

Further Reading:

Essence and Alchemy: A Natural History of Perfume by Mandy Aftel

1900s Lady by Kate Caffrey

War Paint: Madame Helena Rubinstein and Miss Elizabeth Arden, Their Lives, Their Times, Their Rivalry by Lindy Woodhead

Art of Perfume: Discovering and Collecting Perfume Bottles by Christie Mayer Lefkowith

Masterpieces of the Perfume Industry by Christie Mayer Lefkowith

Perfume: Joy, Scandal, Sin – A Cultural History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present by Richard Stamelman

I was interested to read about Harriet Hubbard Ayer’s perfumes, since I own a book that she wrote about beauty – which I do want to write about on the Virtual Dime Museum down the road. She did a couple of makeovers (with photos) that are really funny.

Wonderful post. I love perfume. I wore Chanel No. 5 for years. I’m surprised though that you didn’t mention Creed as one of the earlier perfumers. And ick on the Belladonna drops, but LOL about Queen Alexandra and the enamel. She did have a tendency to look like she had a portrait in the attic that aged while she didn’t.

I’ve never heard of Creed (quick jaunt to wikipedia)–how neat. I must read more on the firm. Do you have any suggestions?

I do want to write about on the Virtual Dime Museum down the road. She did a couple of makeovers (with photos) that are really funny.

Please do! I’ve always been interested in cosmetics.

Fascinating post (and a very interesting blogging subject-I’ll certainly be back). Would you consider submitting to a blog carnival I’m hosting this month, the Fabulous! Festival?

Welcome to my blog anastasia! I’d be happy to submit to the blog carnival you’re hosting this month.

I am looking Nestle Superset Wave Lotion used up thru the 1990s. It seems to be off the market and it was wonderful. Do you know who bought it out and what name it is currently sold under? I used it for years as did my mother and grandmother and I want some more.

Judy–If the company still exists, you should contact Nestle or look for setting lotion at your local beauty store.

This antique dealer is selling a full bottle. But I can’t vouch for the safety of the old contents.

http://www.goantiques.com/detail,nestle-superset-wave,1448494.html

This blog Is very informative , I am really pleased to post my comment on this blog . It helped me with ocean of knowledge so I really believe you will do much better in the future . Good job web master .

I have a passion of perfumes, and I also run a small perfumes sales business. I look

around for posts like yours so I can keep myself updated. I consider the scent of perfumes

as an art because every perfumes’ scent is unique in its own way just like an artist

paints unique pictures. I even run my own blog for perfumes.

I ‘m a perfumes freak, so thanks for the post. I was searching “La Belle Epoque” . I really want to know what had happened to it. Did the company stop producing it, or they are producing it under a new name? If anyone can help me, I would be preciate. Thanks.

I have an old perfume bottle that I’m trying to identify the age, history etc. It has script Elizabeth Arden on one side. On the back it has a small foil label, Arden skin tonic. The bottle has a glass stopper. Can you help?

Really like your well researched blog. You are certainly right that a new phase of creating perfumes began with the creation of synthetic fragrances towards the end of the 19th century, but Paris had a long tradition of being a centre for perfumes. As early as 1807 there were 139 perfumeries selling their products in Paris and this had become 280 by 1867. By that time a firm like Chiris was already 100 years old and Guerlain well established.

Hi – While walking on the beach today, I found an old bottle, with the name Evangeline stamped on it. It has the name on the front and back of the bottle and again on the neck. On the bottom part of the bottle, it says “Design registered” and on the other side: “Min. contents 6 0 (there may have been a dot between the 6 and the 0, but I don’t see it now). On the very bottom of the bottle, it is once again stamped Evangeline. Is it a bottle from a beauty product or something else?