France may have been a Republic, but the glories of its aristocracy lived on. Granted, the upheaval of the last one hundred years resulted in a fragmented upper class, and the last vestiges of their political power died with the Boulanger scandal; nevertheless, its members remained incredibly exclusive, envied, and emulated.

France may have been a Republic, but the glories of its aristocracy lived on. Granted, the upheaval of the last one hundred years resulted in a fragmented upper class, and the last vestiges of their political power died with the Boulanger scandal; nevertheless, its members remained incredibly exclusive, envied, and emulated.

To be an accepted member of le gratin, or upper crust, one was required to have “an up-to-date jacket and a fairly old title.” These qualifications were further stratified into the old aristocracy and the fast and smart Tout Paris, of which the former was then broken down into Legitimists and Orléanists, Bonapartists and Empire aristocracy descended from the twenty-four families Napoleon ennobled, the even more exclusive Catholic society, and the Good Protestant Society, known as the “BPS”. Below them were the wealthy industrialists from the provinces (silk barons from Lyons, shipping magnates, etc), well-bred members of the Bourse, and a few titled Jewish families (i.e. Rothschilds).

In Paris, the purest gratin lived in Faubourg Saint-Germain, where black-clad dowagers looked down upon frivolity and rarely opened its doors to outsiders. The smarter set, the aforementioned Tout Paris, lived in elegant mansions along the Champs-Élysées or equally elegant apartments above Baron Haussmann’s boulevards. Tout Paris encompassed the smart, the wealthy, the best-dressed, and the well-born, and filled the social pages of Paris’s newspapers. Most were ardent Anglophiles who aped the Prince of Wales’s sartorial tastes and appetite for women, food, entertainment, and gambling. As in England, society revolved around the club, sporting events, and house parties, but unlike in England, club life—the most exclusive being the Jockey, the Agricole, the Travellers’, and the Royale—was social and exciting, with exhibits, balls and concerts that women could attend.

The aristocratic Parisienne lived a life of demanding leisure. Her day began at ten o’clock, where she drove, rode or walked in the Bois de Boulogne; at half-past eleven she would return home to change for luncheon or perhaps a wedding or christening; the afternoon saw her dressed to the nines for a charity bazaar or a vernissage in an art gallery; and later she may attend a garden party à l’anglaise. The second half of her day included five o’clock tea (le fif-o’-clock), paying calls on her friends and acquaintances, fittings with her dressmaker, milliner and corsetière, and squeezed between everything else were appearances as public lectures or exhibits until the evening, when she would change into evening attire for dinner, a reception, musicales, the Opéra or theatre, or a ball.

The aristocratic Parisienne lived a life of demanding leisure. Her day began at ten o’clock, where she drove, rode or walked in the Bois de Boulogne; at half-past eleven she would return home to change for luncheon or perhaps a wedding or christening; the afternoon saw her dressed to the nines for a charity bazaar or a vernissage in an art gallery; and later she may attend a garden party à l’anglaise. The second half of her day included five o’clock tea (le fif-o’-clock), paying calls on her friends and acquaintances, fittings with her dressmaker, milliner and corsetière, and squeezed between everything else were appearances as public lectures or exhibits until the evening, when she would change into evening attire for dinner, a reception, musicales, the Opéra or theatre, or a ball.

The Paris season was divided into two: the little season from December to Easter, and the Grande Saison from April to mid-June. The little season was filled with debut balls (bal-blancs for young unmarried women), dinners, musical concerts, horse races, and the opera. In the short week after the close of the little season, French society either visited their châteaux or went abroad. Then the Grande Saison opened with the Concourse Hippiques, a horse show held in the Palais d’Industrie on the Champs-Élysées, where ladies and couturiers showed off the latest spring fashions. The Paris Salon opened on the first of May, where the most fashionable artists showed their newest sculptures, paintings, and decorative art, but this was also an excuse to display one’s latest frock, and instead of examining the art ladies eyed one another, particularly if a smart painter like Sargent or Boldini unveiled his portrait of one’s social rival.

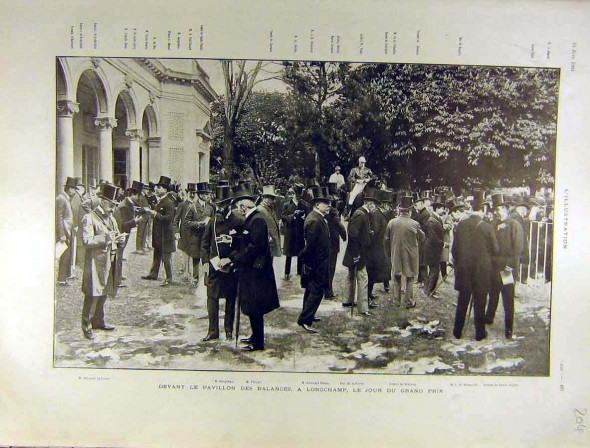

Despite its name, the Grande Saison was actually quite short, and by mid-June, the Grand Prix de Paris marked its definite end. The Grand Prix ran on the second Sunday in June, on the vast course of Longchamp in the Bois de Boulogne, and the crowd as described by Guy Wetmore Carryl was considerable:

Despite its name, the Grande Saison was actually quite short, and by mid-June, the Grand Prix de Paris marked its definite end. The Grand Prix ran on the second Sunday in June, on the vast course of Longchamp in the Bois de Boulogne, and the crowd as described by Guy Wetmore Carryl was considerable:

“For an hour before the commencement of the races on Grand Prix day, all the approaches to Longchamp are filled with a swiftly-moving throng of vehicles of every imaginable description, from huge twenty horse-power automobiles down through all the varying types of motor carriages, private coaches, drags, carts and victorias, to the humble public cab or lumbering charabanc, or open omnibus, holding from twenty to fifty persons, and drawn by three, six, or eight horses, as the case may be. It is a veritable river of conveyances, rising in the city’s heart and flowing with ever-increasing volume along the Avenues des Champs-Élysées and du Bois de Boulogne, fed by innumerable side-street tributaries, until it breaks into a sort of delta at the gates of the Bois and swirls on to Longchamp by a score of different approaches.”

Once again fashion ruled the proceedings, and the latest summer modes were displayed by ladies and mannequins, and after this race, Society closed their Parisian homes to decamp for the French Alps or for Trouville, Ostend, Baden-Baden, Biarritz and Aix-les-Bains. The sporting-minded might hare off to Scotland for grouse-shooting in August, and the months of September and October were the “enchanted months in which to stay in the great châteaux.” House parties lasted for as much as a month at a time, and guests entertained themselves with hunting and shooting, dining, private theatricals, and dances. Bicycling retained its hold on the French long after the craze died away in Britain and America, and it was common for members of le gratin to gather together for cycling parties along the crisp, delicious countryside. At the end of these “enchanted months,” the social round would begin again!

Further Reading:

Elegant Wits and Grand Horizontals by Cornelia Otis Skinner

A Society Woman on Two Continents by Sally Britton Spottiswood Mackin

Proust and His World by William Sansom

Edward and the Edwardians by Philippe Jullian

Very interesting and informative article. I have learnt a lot.

Can any of you tell me the economic activities, political participation and the cultural characteristics of the aristocracy during the belle epoque?

The Skinner book is a good resource, as is Belle Epoque: Paris in the Nineties by Raymond Rudorff and Dawn of the Belle Epoque by Mary McAuliffe.