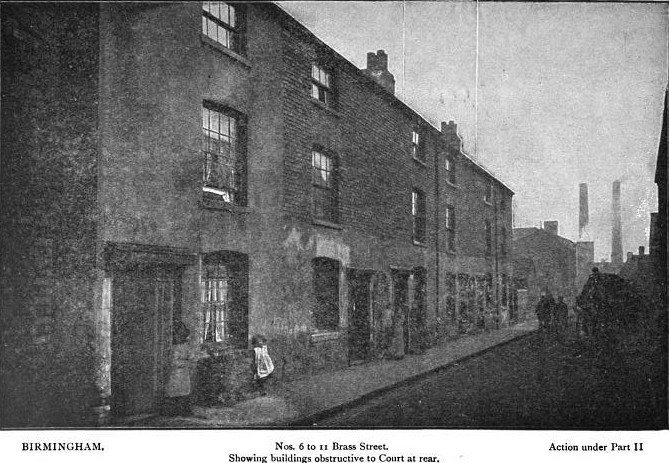

As cities began to expand after the Civil War, the crowded quarters boded ill for health, and the suburbs began to lure city dwellers with promises of fresh air and the pleasures of country living. One commuter of 1883 wrote:”

As cities began to expand after the Civil War, the crowded quarters boded ill for health, and the suburbs began to lure city dwellers with promises of fresh air and the pleasures of country living. One commuter of 1883 wrote:”

I live in a good neighborhood, close to a country station, ten miles from the city, where each house has its garden…The families are not rich, but intelligent and of good taste. They like to make their salaries go as far as possible, to have something for concerts and journeys… Each one raises potatoes enough for the year, summer berries and green corn for the season…Everybody says a garden is a great help.

This was a complete opposite of what was occurring in Britain, where a “rural exodus” of would-be farm laborers and domestic servants abandoned the countryside for industrial and office positions in the major cities. Though there was a push for “fresh air” and a sentimental view of the vibrant landscapes of suburban and rural Americans, only the wealthy could afford to leave the city to enjoy both bucolic attributes. Wanting to follow the advice of the leading physicians of the day, and consume conspicuously, America’s wealthy elite began to build country houses.

The American country house, as an unique, individual entity, developed in their fullest form after 1885. Yes, there were the large farms along the Hudson, which were built by the early Dutch settlers, and the plantation houses of the antebellum South, but the prototypical “country house” was created as a social center, a product of wealth and leisure, and a place where the privileged classes could “escape” the hustle and bustle of city life. Once the Vanderbilt family threw down the gauntlet with such estates as Idle Hour in Long Island, The Breakers and Marble House in Newport, and Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina, America’s wealthiest citizens began a frenzy of building which resulted in a score of celebrated country houses and estates in all corners of the U.S.

The American country house, as an unique, individual entity, developed in their fullest form after 1885. Yes, there were the large farms along the Hudson, which were built by the early Dutch settlers, and the plantation houses of the antebellum South, but the prototypical “country house” was created as a social center, a product of wealth and leisure, and a place where the privileged classes could “escape” the hustle and bustle of city life. Once the Vanderbilt family threw down the gauntlet with such estates as Idle Hour in Long Island, The Breakers and Marble House in Newport, and Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina, America’s wealthiest citizens began a frenzy of building which resulted in a score of celebrated country houses and estates in all corners of the U.S.

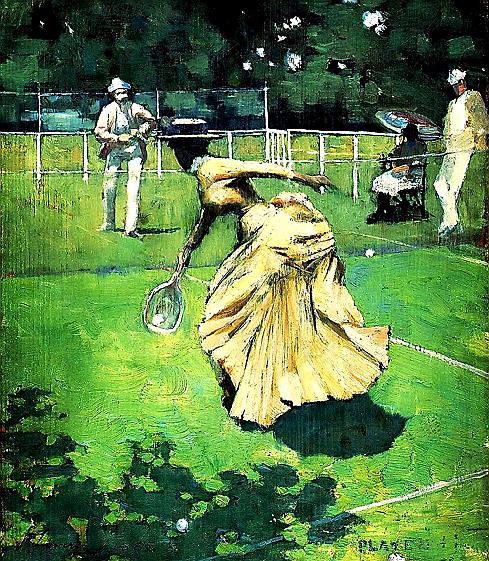

But these socialites wanted not simply a country house, but an “all-around country place,” complete with a variety of other structures such as lodges, stables, garages, gazebos, terraces and other garden architecture, glass houses, sports buildings, workers’ cottages, model farm and churches. And many were situated on large plots of land where they could hunt, ride, play polo, croquet and other outdoor sports. In a way, these Americans wished to mimic the much-vaunted “English country house,” and those grandiose characteristics served to distinguish these houses built around the turn of the century from any other dwelling designed and built in America up to then. However, according to Clive Aslet in 1990’s The American Country House, the British model upon which Americans based their estates upon had moved away from its original focus by the 1890s: “its meaning had both narrowed and spread…because the country house no longer occupied the position o f real power it had held in previous generations; the motive forces were now prestige, tradition, gardening, and sport…[T]he people who built new houses tended to prefer the illusion to the substance of country life [and] to many people it was important to be near a major city.”

f real power it had held in previous generations; the motive forces were now prestige, tradition, gardening, and sport…[T]he people who built new houses tended to prefer the illusion to the substance of country life [and] to many people it was important to be near a major city.”

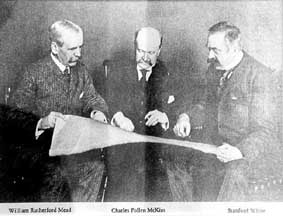

Though being part of a landed class did not secure political influence or ensure that the owner would have some role in running the country, nor was the American country house a place where political stratagems were hatched, the construction of an estate in the country was considered vital to anyone claiming to a part of the smartest, wealthiest social sets. When a Vanderbilt, or an Astor, or a Drexel wanted a country house, they turned to the top architects of this time: H. H. Richardson (-1886), Frank Furness, Richard Morris Hunt and the celebrated firms of McKim, Mead and White (the “White” being Stanford White) Warren and Wetmore, and Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge. The popular architectural styles of the day were:

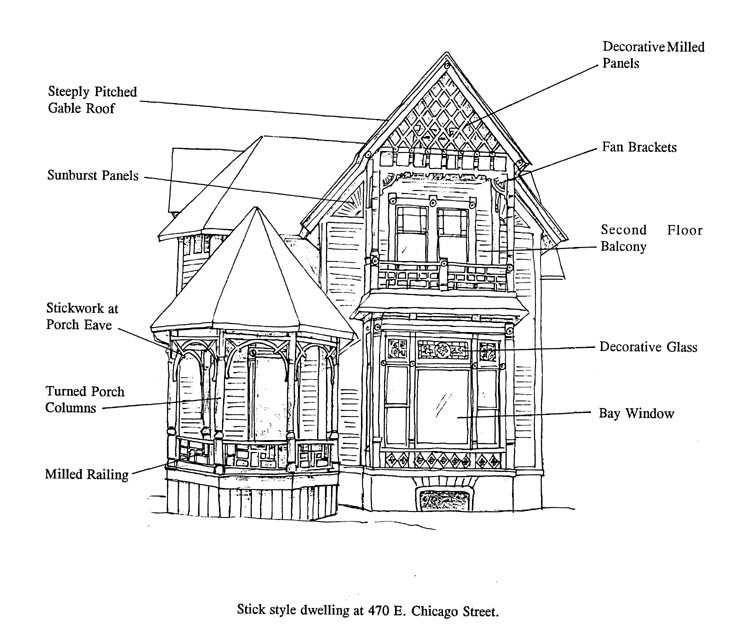

- Stick Style, which derived from the Carpenter Gothic style, and embodied the idea that architecture should be truthful

- Queen Anne, which was generally a eclectic mash of an asymmetrical silhouette shaped by turrets, towers, gables, and bays

- Shingle Style, which grew from the Queen Anne style, but was less ornate and more horizontal than the typical Queen Anne house

- Richardsonian Romanesque, named after architect H.H. Richardson, who interpreted Romanesque architecture into a distinctly different style, and created one which abandoned the vertical silhouettes and smooth stone facings of earlier times.

- Beaux Arts, which was named for the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and refers to the aesthetic principles practiced by the American architects who trained there.

- Classical Revival, which was less theatrical than the Beaux Arts and based primarily on the Greek architectural orders.

These aforementioned architects designed, and popular architectural styles appeared in, not only country estates, but clubs both urban and suburban, museums, libraries, railroad stations, churches, monuments, bridges, city halls and other government buildings, banks, hospitals, schools and universities. Richardson’s most celebrated work is Trinity Church in Copley Square, Boston, but the William Watts Sherman House in Newport, RI and the Crowninshield House, also in Boston, which is also the earliest, still surviving, example of his private residence work, are equally famous. The designs of Furness were mainly found in Philadelphia and outlying areas, and over the course of his 45-year career, he designed more than 600 buildings, one of which what is now the Ritz-Carlton Philadelphia. Hunt was and is considered the preeminent individual architect of the Gilded Age. He designed not one, but five Newport cottages, and was responsible for Alva Vanderbilt’s glorious Marble House. Ironically, he also designed the cottage of her second husband, O.H.P. Belmont.

The stamp of McKim, Mead and White can be found throughout New York City, almost all of which have survived today. Ex. the Washington Arch in Washington Square Park, the Morgan Library, and Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus. It is Warren and Wetmore who are responsible for Grand Central Station, the New York Yacht Club and CBS Studio Building, which at the time was built for the Vanderbilt family for use as a guest house. The firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge grew out of Richardson’s architectural practice, when, after the latter’s untimely death, Mssrs Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge completed all of Richardson’s commissions. Based in Boston, this firm designed the South Station, the Ames Building, and a new campus for the Harvard Medical School in 1906.

The stamp of McKim, Mead and White can be found throughout New York City, almost all of which have survived today. Ex. the Washington Arch in Washington Square Park, the Morgan Library, and Columbia University’s Morningside Heights campus. It is Warren and Wetmore who are responsible for Grand Central Station, the New York Yacht Club and CBS Studio Building, which at the time was built for the Vanderbilt family for use as a guest house. The firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge grew out of Richardson’s architectural practice, when, after the latter’s untimely death, Mssrs Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge completed all of Richardson’s commissions. Based in Boston, this firm designed the South Station, the Ames Building, and a new campus for the Harvard Medical School in 1906.

Now that this wealthy American possessed a country house, it was time to fling open the doors for a week-end party. As with all new things suddenly deemed fashionable, etiquette sprang up to guide those uncertain hostesses thrust into a new world. According to The Etiquette of New York To-day, “the success of a house-party depends on inviting people who know each other well, or who, when introduced, will find each other’s acquaintance agreeable.” When a hostess sent out invitations, she was advised to definitely state the period of the visit, which is where the word “week-end” was formed, though the British disdained this Americanism for “Saturday to Monday.”

Now that this wealthy American possessed a country house, it was time to fling open the doors for a week-end party. As with all new things suddenly deemed fashionable, etiquette sprang up to guide those uncertain hostesses thrust into a new world. According to The Etiquette of New York To-day, “the success of a house-party depends on inviting people who know each other well, or who, when introduced, will find each other’s acquaintance agreeable.” When a hostess sent out invitations, she was advised to definitely state the period of the visit, which is where the word “week-end” was formed, though the British disdained this Americanism for “Saturday to Monday.”

Guests would arrive by rail, and since so much of the Four Hundred’s wealth was built upon railroads, many estates were right on the railroad lines (or was it vice versa?). In some houses, the cards bearing the names of guests were found in their rooms, and they were expected to tie their keys to their trunks or suit cases on the cards to aid their maids and valets in keeping track of their belongings. The party was largely informal, with hostesses offering guests the option of rising for breakfast or having it in their rooms, and allowing them the opportunity to take part in any activity they chose or did not choose. This was all quite similar to what occurred in Britain, with one exception–week-end in the country did not include the casual adultery and bedroom swapping common within the Marlborough House Set–a fact that shocked many an American who moved within European social circles.

Though English-style country estates were built after the 1920s, the period between 1885 and about 1920 is considered the golden age of the American country house. Because few if any of the houses built were intended as dynastic seats, to be handed down from generation to generation as did the Europeans, and the advent of income tax ate away at the fortunes of the Four Hundred’s outrageous fortunes, many of these famed Gilded Age manors fell into disrepair and neglect. Many still stand, whether preserved as museums (such as the Newport mansions), or as businesses and schools, though many more were demolished or destroyed by disasters (such as Clarence McKay’s Harbor Hill).

Though English-style country estates were built after the 1920s, the period between 1885 and about 1920 is considered the golden age of the American country house. Because few if any of the houses built were intended as dynastic seats, to be handed down from generation to generation as did the Europeans, and the advent of income tax ate away at the fortunes of the Four Hundred’s outrageous fortunes, many of these famed Gilded Age manors fell into disrepair and neglect. Many still stand, whether preserved as museums (such as the Newport mansions), or as businesses and schools, though many more were demolished or destroyed by disasters (such as Clarence McKay’s Harbor Hill).

Further Reading:

The American Country House by Clive Aslet

Newport Villas: The Revival Styles 1885-1935 by Michael C. Kathrens

Gilded Mansions: Grand Architecture and High Society by Wayne Craven

Harbor Hill: Portrait of a House by Richard Wilson

The Etiquette of New York To-day by Ellin T. Craven Learned

American Country Houses of To-day by Samuel Howe

American country homes and their gardens by John Cordis Baker

One Hundred Country Houses: Modern American Examples by Aymar Embury

Society in the country house by T. H. S. Escott,

Vintage Designs (interiors of many Gilded Age mansions and houses)