January 1 marked the 208th anniversary of the formal opening of the White House, at Washington, as the official home of the President of the United States. Having taken possession of the newly-built “President’s House” in November of 1800, President John Adams threw an official “housewarming” party for this now most historic and most important dwelling in America. The cornerstone of the President’s House was laid October 13, 1792, and the work was carried on as rapidly as the meager appropriations of Congress could allow. In every decade, and with the incoming of each new President, more and more money was appropriated to run the White House until in 1909, the budget for the White House expenses amounted to an average of $1000 a week (apprx $23,000 in 2008 money).

January 1 marked the 208th anniversary of the formal opening of the White House, at Washington, as the official home of the President of the United States. Having taken possession of the newly-built “President’s House” in November of 1800, President John Adams threw an official “housewarming” party for this now most historic and most important dwelling in America. The cornerstone of the President’s House was laid October 13, 1792, and the work was carried on as rapidly as the meager appropriations of Congress could allow. In every decade, and with the incoming of each new President, more and more money was appropriated to run the White House until in 1909, the budget for the White House expenses amounted to an average of $1000 a week (apprx $23,000 in 2008 money).

The source of continual expense was due to mansion being constructed of Virginia freestone, which was exceedingly porous, which needed a thick coat of white lead every ten years to keep the dampness from penetrating to the interior. Because of the cramped space and need for constant maintenance, many historians, and certainly former tenants of the White House, stated that it was not until President Roosevelt remodeled the building that it was made entirely sanitary and healthful.

When he came to office in 1902, President Roosevelt rebuilt the White House practically from scratch, architects considering it “necessary to reconstruct the interior of the White House from basement to attic, in order to secure comfort, safety, and necessary sanitary conditions.” The restoration conformed to the original design, though two wings were added, one being used as the Temporary Executive Offices, and the other for use on social occasions. These changes and improvements were made at a cost of over $600,000 ($12,000,000 in 2008 dollars).

The first tenants of the White House, President and Mrs John Adams immediately required $15,000 ($180,000) to provide furniture, and the first appropriation for repairs was of the same amount but seven years later! Thomas Jefferson had his office outside the White House on the site occupied by the resent Executive offices, and in 1818, Congress appropriated $8,137 ($11,000) for enlarging the offices west of the Presidents House. The South portico was finished subsequent to 1823, at a cost of $19,000 ($325,000); the East Room was finished and furnished for $25,000 ($480,000) in 1826; and three years later, the North Portico was added, in accordance with the original plan, at an expense of $24,769.25. The White House was first lit by gas in 1848, and a system of heating and ventilating was installed in 1853. Four years later the stables and conservatory east of the White House were removed to make room for the extension of the Treasury Building.

The first tenants of the White House, President and Mrs John Adams immediately required $15,000 ($180,000) to provide furniture, and the first appropriation for repairs was of the same amount but seven years later! Thomas Jefferson had his office outside the White House on the site occupied by the resent Executive offices, and in 1818, Congress appropriated $8,137 ($11,000) for enlarging the offices west of the Presidents House. The South portico was finished subsequent to 1823, at a cost of $19,000 ($325,000); the East Room was finished and furnished for $25,000 ($480,000) in 1826; and three years later, the North Portico was added, in accordance with the original plan, at an expense of $24,769.25. The White House was first lit by gas in 1848, and a system of heating and ventilating was installed in 1853. Four years later the stables and conservatory east of the White House were removed to make room for the extension of the Treasury Building.

How the White House received its name is a source of debate. One source states that Washington so named it in honor of the name born by the home of Martha Washington, while others have it that Martha never lived in a building named the White House, but the name belonged to the home where she and George became engaged. A third source states the house was originally called “The Palace,” but a strong “anti-monarchical sentiment” frowned on this and Congress formally declared it “The Executive Mansion,” and by that name and “The President’s House,” it was known until it was burned by the British in 1814. Then, when its blackened freestone walls were repainted white to hide the traces of the fire, it was rechristened “The White House”.

Though President Washington died before the White House was completed, he left his stamp indelibly upon it. He named the place where the capitol of the United States was to be “District of Columbia” and then a competition was opened to all architects to design the Executive Mansion. The winner was James Hoban, who received $500 ($6000) at first prize, for a design he based on the newly-built mansion of the Duke of Leinster in Dublin, Ireland (Hoban’s native city). When the Adams’ took residence in the mansion, they were less than impressed. The driver, who transported them and their effects from Baltimore, had lost his way, and when they finally arrived in Washington, it was night and the servants could hardly find lights to make the rooms distinguishable. Mrs Adams found them “exceedingly barn-like” in their unfinished and unfurnished state, and they were uncomfortable and cold. By New Year’s of 1801, the downstairs rooms were still unfurnished and unfinished, and Mrs Adams used the East Room in which to dry the household linen and the State parlors were so in name only.

Though President Washington died before the White House was completed, he left his stamp indelibly upon it. He named the place where the capitol of the United States was to be “District of Columbia” and then a competition was opened to all architects to design the Executive Mansion. The winner was James Hoban, who received $500 ($6000) at first prize, for a design he based on the newly-built mansion of the Duke of Leinster in Dublin, Ireland (Hoban’s native city). When the Adams’ took residence in the mansion, they were less than impressed. The driver, who transported them and their effects from Baltimore, had lost his way, and when they finally arrived in Washington, it was night and the servants could hardly find lights to make the rooms distinguishable. Mrs Adams found them “exceedingly barn-like” in their unfinished and unfurnished state, and they were uncomfortable and cold. By New Year’s of 1801, the downstairs rooms were still unfurnished and unfinished, and Mrs Adams used the East Room in which to dry the household linen and the State parlors were so in name only.

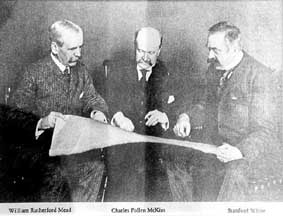

When the mansion was rebuilt in 1814, Hoban was hired for $1600 ($16,000) a year, and Congress voted the sum of $500,000 ($5M) for rebuilding and repairing the public buildings burnt in the fire, with the larger part of the money spent on the Executive Mansion. The first President to live in the rebuilt mansion was James Monroe, who opened his official residence in January 1, 1818. Between then and 1902, the White House was remodeled and repainted and refurnished according to the current Presidents’ tastes and that of his wife’s. When President Roosevelt appropriated some $600,000 ($12M) from Congress, the legendary architectural firm of McKim, Mead and White were placed in charge of the work, with directions to complete the work in four months. They did this ably, and the first official function in the restored White House occurred on December 18, and at the New Year’s reception, Jan 1, 1903, when the new White House was reopened to the public.

In their report, McKim, Mead and White gave the following facts:

In their report, McKim, Mead and White gave the following facts:

“The entire lower floor was used for house service. The principal rooms at the southeast corner were occupied by the laundry; the central rooms on either side of the main corridor were used for heating and mechanical plants; the kitchens occupied the northwest corner; and much of the remainder of this floor was occupied by storerooms and servants’ bedrooms.

Of the floors of the first story, those under the main hall, the private dining room, and pantry, were found to be in good condition. The floor of the State dining-room, while not showing settlement, was so insufficiently supported as to cause the dishes on the sideboards to rattle when the waiters were serving, and the plastering below was badly cracked from excessive vibration. In many places where the plaster was removed, evidence of the fire of 1814 were visible. Also cut into the stonework were found many names, evidently of workmen employed on the construction.

There was scarcely a room in the house in which the plaster was in good condition. In a number of instances as many as five layers of paper were found, and when the paper was removed, the plaster came also. The second floor showed such a degree of settlement as to make an entirely new floor necessary.

The attic, occupied by servants, was reached only by the elevator. The roof drainage had been carried through the roof, and thence on top of the attic floor to central points, descending to the ground through the house itself. The electric wiring was not only old, defective and obsolete, but actually dangerous, as in many places beams and studding were found charred for a considerable distance about the wires where the insulation had completely worn off.

In short, it was necessary to reconstruct the interior of the White House from basement to attic, in order to secure comfort, safety and necessary sanitary conditions. “

When they completed their renovation, the conservatory on the west side was replaced with an esplanade leading to the new Executive Office, and the public entrance was now through a colonnade on the east. This led to the basement corridor, on which walls were hung with portraits of the mistresses of the White House. Broad stairways led to the main corridor, from which access is had to the East Room, and the Blue, Green and Red rooms, which took their name from the color of the decorations and furnishings.

|

The East Room, or State parlor, was used for receptions, and was 40ft wide and 82 ft in length, with a ceiling 22ft high from which dripped three massive crystal chandeliers. The walls were paneled throughout with wood, save for a base of red Numidian marble, the panels being enclosed between pilasters supporting a finely modeled cornice. The decorations of walls and ceiling were white and gold, with moldings and tablet ornamentation in relief, and window draperies of old gold. |

|

The Blue Room, oval in shape, is the President’s reception room. The walls were covered with rich blue corded silk, and the window hangings were blue with golden stars in the upper folds. On the mantle stood the clock of gold presented by Napoleon I to Lafayette, and by him to Washington. |

|

The Green Room, had on the wall green velvet with white enamel wainscoting. In front of the white marble mantel was a screen of old Gobelin tapestry which was presented to Mrs Grant by the Emperor of Austria. A lacquer cabinet was presented to America by Japan in 1858 in honor of the first American ships to enter Japanese ports. |

|

The Red Room walls and window draperies were of red velvet, and a cabinet of mahogany and gold contained seven exquisitely dressed Japanese dolls presented to Mrs Roosevelt by the Japanese Minister. |

|

At the opposite end of the corridor, at the west end of the building, the State Dining Room was paneled in dark English oak, and decorated with the heads of American big game. The white marble mantle was surmounted by an old Flemish tapestry, and the mahogany table seated 100 guests. |

|

The President’s Room and the Cabinet Room were in the Executive Office, west of the White House. |

Upstairs, the old Cabinet Room, which was accessed through the stone stairway near the main entrance of the East Room, was used by President Roosevelt as his workroom. Completing the renovation, all offices on this same floor were transformed into bedrooms for the family, creating a White House which finally served its purpose: a private residence for the President and his family, and a State residence for formal events.

Resources used: Inside History of the White House by Gilson Willets; The Standard Guide of Washingon, 1905 edition; American Estates and Gardens by Barr Ferree. Current money calculations provided by The Inflation Calculator.

For more information:

TR Renovation – White House Museum

The Changing White House – PBS