Society in our land has long ago taken the chief public schools into its social calendar as most important items for providing recreation, pleasure, and delightful entertainment during the course of the year from January to December. Almost each month brings its own special school into prominence, or its own particular social event in connection with the various places of education to which boys from the upper classes resort.

Three times annually does Eton help to provide the day off, so to speak, for Society in this way. These occasions comprise the annual cricket match against Harrow, at Lord’s; the annual match against Winchester, played alternately at Eton and Winchester; and the famous Fourth of June celebrations.

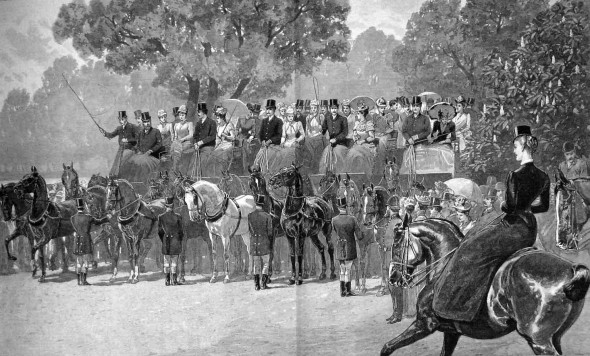

The latter must be dealt with first in this article, because on the Fourth of June, the great school under the shadow of Windsor Castle has the entire field to itself in the regard of social England. On that day Eton gives itself up to pleasure and enjoyment pure and simple, from early morning till late at night. Paddington Station in London has its platforms packed soon after breakfast with innumerable “mothers, sisters, aunts, and cousins,” in their latest and most fascinating summer costumes, a blaze of beauty, aristocracy, and charm, all waiting for trains to carry them to Windsor, in order to see “dear Roland” lead the procession of boats, or to spend a happy hour or two with “darling Algy,” who has recently been made a prepositor.

Of course, though there are entertainments and pleasures galore to be enjoyed during the afternoon on that day at Eton, the piéce de résistance is the evening procession of boats from Surly to Datchet, with the fireworks afterwards to enliven the final scene of the day.

For some decades now the Eton v. Harrow cricket-match at Lord’s in July has been reckoned one of the principal days in the list of Society’s summer programme in London–or rather, it would be more correct to say “two days,” for this match always begins on a Friday and continues on the Saturday. The attendance never fails to run into many thousands if the weather is at all propitious; and it must be acknowledged that the match has ever been favoured greatly in this respect, for the two teams have seldom had any really wet days to contend with on these occasions.

To many folks, however, the Eton v. Winchester match is a more enjoyable function than the annual contest at Lord’s, despite the latter’s immense social predominance. For when you can see the delightful scenery round Eton better than on those charming summer days that find the Wykehamists in the playing-fields by the river, supported by an admiring crowd of mothers and aunts, to say nothing of sisters and cousins. Should the match be at Winchester, however, Society from London is found in crowds at Waterloo, trying to get early trains down to the historic city of Itchen. Carriages are rapidly filled, and the famous High Street at Winchester sees a galaxy of ladies invade it with more conquering attributes than ever did the Saxon or Dane in bygone days. Winchester Meads, where the great crowd betakes itself to see the cricket and to enjoy the social triumph, are just as lovely as are the banks of the Thames at Eton.

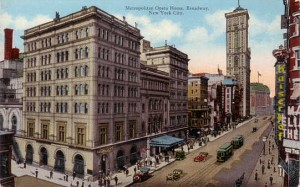

A cricket-match, of course, is almost an ideal event for a fine show of dress and for social entertainment. Perfect summer weather, charming rural scenery, the enthusiasm of the schoolboys, the gallantry of masters and governors, the game itself, the strawherries and cream, the long drive through leafy lanes to reach the school—all these possess wonderful fascination for the average lady, be she mother or daughter. When the match is at Lord’s it somewhat lacks one or two of these things, but it makes up for them by being in town, where still more friends may be expected to turn up, and where the ladies may look forward to meeting even more of their acquaintances of the stronger sex. This is why Rugby v. Marlborough provides a scene only second to Eton v. Harrow in school-matches on that classic ground of Lords each year.

Whilst it is our intention to pass by the average speech-day at the public schools (though such days are truly often social gatherings of some renown in their various spheres), yet we must say a word about the greatest of them, which is undoubtedly that of Harrow. There is perhaps only one special day of the year when London Society betakes itself m waste to the Hill for pleasure and entertainment, and this is the day. To stand in the country road that leads to the fine speech-hall of the celebrated school, and to watch the crowds of welldressed women and men who come to Harrow to hear the speeches, is like standing in the Row some fine summer afternoon between four and half-past five.

The Hill on this occasion shows us of its best in every way. The dark blue of Harrow’s sporting teams is occasionally in evidence, but for once silk hats and frock coats predominate on the Hill in a manner that is not generally common there. The Etonian on ordinary days, even to stroll through the streets of Windsor, must wear that silk hat, but the Harrovian on ordinary days wears a straw hat, or none at all. It is only when his feminine relations come to the Hill in full force of all-pervading beauty and brilliance that the Harrovian feels it incumbent on him to rise fully to the occasion in the way that Eton does.

Let us make a sudden transition from the summer social delights at the great schools to the winter ones. The most striking of these, often patronised by Royalty, and always by a large number of the aristocracy, is the Latin Play each December at Westminster School. Certain high officials, such as the Judges, Cabinet, Speaker of the Commons, and their wives, have a prescriptive claim to be invited. When one recollects that the Play is always performed in the old dormitory of the school one hardly wonders that the place is crowded, that space is much restricted, and that hundreds of ladies of high degree have often to be “turned empty away.”

Mothers and boys have, twice a year, a fine time for enjoyment, if they are connected with Radley College. When Radley holds its annual “ Gaudy,” a term still applied there to the speech-day, as it used to be at all great schools centuries ago, there is usually such a scene as is only second to Harrow‘s on similar occasions. Ladies of fashion and rank travel down from London to the Berkshire school in large numbers to be present, and the many interesting features of the day are much appreciated by the proud mothers and admiring sisters as they stroll around the beautiful grounds attached to the school.

Marlborough gets in its opportunity for joining in the crush of rank and fashion when its “Commemoration ” comes round each summer. Society has always shown itself most favourable to Marlborough of the newer schools during the past two or three decades, and the college in Wiltshire duly rejoices.

— The Lady’s Realm

I know well established families above a certain income HAD to send their sons away to school, so the idea of catching up with beloved Roland three times a year must have sounded very appealing. Colourful, sporty, beautifully dressed and very social.

But did anyone ever think why isn’t Roland in his own bedroom, eating dinner with us every night of the week? I miss my sons now they are adults and have families of their own, but at such a young age I would NEVER have let them leave home.

Sending boys away to public school was to acclimate them to the ways and “language” of their upper class and aristocratic society, so I assume they just didn’t–and still don’t today–think it was separation. It was helping your son get ahead in life.

Wow; nice silhouette of what people were focused on during Winston Churchill’s school days.

Exactly! Thanks for stopping by. 🙂