With summer came the great exodus from the sweltering weather of London. The railways had opened England’s coastal resorts to the middle classes in the Victorian era, and the tramways and motorbuses opened them to the working classes, enabling them to take part in the popular concept of the “week-end.” Accordingly, the upper classes frequently moved on to Trouville-Deauville or Biarritz–both in France–for their summer getaway.

With summer came the great exodus from the sweltering weather of London. The railways had opened England’s coastal resorts to the middle classes in the Victorian era, and the tramways and motorbuses opened them to the working classes, enabling them to take part in the popular concept of the “week-end.” Accordingly, the upper classes frequently moved on to Trouville-Deauville or Biarritz–both in France–for their summer getaway.

The seaside resort had its roots in the mid-18th century as an extension of the older health regime of the spa where physicians believed the sea to have prophylactic powers at the August spring tides. The first sea-bathing resorts began in North Yorkshire and spread quickly to south-eastern England, the most fashionable being Margate, Brighton and Weymouth. With the royal patronage of the Prince Regent upon Brighton, the seaside resort became the fastest-growing kind of British town by the first half of the 19th century, and by the 1900s, every English and Welsh coastline was studded with resorts of different sizes, and every possible market could find a congenial holiday home in one or other of well over 100 substantial coastal resorts, the largest of which had well over 50,000 year-round residents.

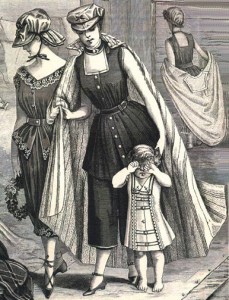

Ensconced in a boarding house, or perhaps a sea-side villa, the intrepid holidayers would venture to the coastlines for the morning dip. Children were handled by nannies attired in straw boaters and stiff white pique dresses, who pushed perambulators in which the babies were almost hidden behind the bathing dresses, towels, wooden spades (for iron ones were forbidden because they could cause injury) for their elder siblings. Despite the relative modesty of bathing costumes, it was considered an article of clothing improper for a mixed crowd and until 1901, both sexes were confined to segregated bathing machines (roofed and walled wooden carts that rolled into the sea) to retain a measure of propriety.

Ensconced in a boarding house, or perhaps a sea-side villa, the intrepid holidayers would venture to the coastlines for the morning dip. Children were handled by nannies attired in straw boaters and stiff white pique dresses, who pushed perambulators in which the babies were almost hidden behind the bathing dresses, towels, wooden spades (for iron ones were forbidden because they could cause injury) for their elder siblings. Despite the relative modesty of bathing costumes, it was considered an article of clothing improper for a mixed crowd and until 1901, both sexes were confined to segregated bathing machines (roofed and walled wooden carts that rolled into the sea) to retain a measure of propriety.

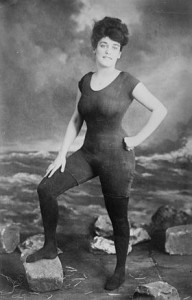

As the only activity for women involved jumping through the waves while holding onto a rope attached to an off-shore buoy, their bathing costume was quite unsuited for real swimming. Made of serge or preshrunk mohair in black, red or navy, it consisted of a knee-length skirt, a pair of bloomers and a tunic, or a combination type with skirt. The costume was then accessorized by long black stockings, lace-up bathing slippers, and fancy caps. The style of costume changed little between the years 1880 and 1907, cap sleeves being the only new concession to fashion. It was Australian swimmer, Annette Kellerman, who heralded the transformation of the bathing costume’s silhouette.

As the only activity for women involved jumping through the waves while holding onto a rope attached to an off-shore buoy, their bathing costume was quite unsuited for real swimming. Made of serge or preshrunk mohair in black, red or navy, it consisted of a knee-length skirt, a pair of bloomers and a tunic, or a combination type with skirt. The costume was then accessorized by long black stockings, lace-up bathing slippers, and fancy caps. The style of costume changed little between the years 1880 and 1907, cap sleeves being the only new concession to fashion. It was Australian swimmer, Annette Kellerman, who heralded the transformation of the bathing costume’s silhouette.

Her performance as an “underwater ballerina” was a version of synchronized swimming involving diving into glass tanks and looking graceful. Since her costume was tailored to suit her movement, she was arrested for indecent exposure because her swimsuit showed arms, legs and the neck. Though Kellerman later changed the suit to have long arms and legs and a collar, it kept the close fit of her first costume. After this event, bathing wear started to shrink, first uncovering the arms and then the legs up to mid-thigh. Collars receded from around the neck down to around the top of the bosom. The development of new fabrics allowed for new varieties of more comfortable and practical swim wear. Until 1860, it was customary for men to swim nude, and after this was banned in 1860, masculine bathing costume followed the lines of womens, consisting of shirt and shorts, made of dark-colored serge. As with women, men’s costume changed by the late 1900s, when a few daring men were seen swimming topless!

was tailored to suit her movement, she was arrested for indecent exposure because her swimsuit showed arms, legs and the neck. Though Kellerman later changed the suit to have long arms and legs and a collar, it kept the close fit of her first costume. After this event, bathing wear started to shrink, first uncovering the arms and then the legs up to mid-thigh. Collars receded from around the neck down to around the top of the bosom. The development of new fabrics allowed for new varieties of more comfortable and practical swim wear. Until 1860, it was customary for men to swim nude, and after this was banned in 1860, masculine bathing costume followed the lines of womens, consisting of shirt and shorts, made of dark-colored serge. As with women, men’s costume changed by the late 1900s, when a few daring men were seen swimming topless!

Sunday heralded the end of the weekend. Bathing on the Sabbath was frowned upon and after morning services, visitors thronged the promenades, attired in their Sunday whites to enjoy the sun, regimental bands, minstrel players and delicious treats sold by vendors. As the dusk fell, servants or hotel staff, or perhaps just the family, busily packed their belongings for the return to London on Monday. Sated and full of sea air, the weekend getaway to the beach was open to nearly all classes and walks of life. For the unforunates who were unable to afford the cost of the trip, charitable organizations brought the beach to them, one well-known London-based charity importing sand to the East End to give the children a taste of the delights of a sea-side resort.