Though the common perception of Mardi Gras links it with New Orleans, the tradition began in Mobile, Alabama in 1703, as that city was the capital of the territory of Louisiane (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama). The Carnival season in New Orleans began with the grand ball of the “Twelfth Night Revellers,” on January 9, and ended on Mardi Gras (or Fat Tuesday, though English-speaking countries called the day “Shrove Tuesday”), which was the eve of Ash Wednesday and marked the close of the festivities and the beginning of the Lenten Season. Because the New York social season (and those of society in many other major cities) closed with Lent, the celebration spread from the South during the Gilded Age and the Four Hundred, as well as everyday New Yorkers, threw a variety of balls and gatherings to mark the occasion.

Though the common perception of Mardi Gras links it with New Orleans, the tradition began in Mobile, Alabama in 1703, as that city was the capital of the territory of Louisiane (Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama). The Carnival season in New Orleans began with the grand ball of the “Twelfth Night Revellers,” on January 9, and ended on Mardi Gras (or Fat Tuesday, though English-speaking countries called the day “Shrove Tuesday”), which was the eve of Ash Wednesday and marked the close of the festivities and the beginning of the Lenten Season. Because the New York social season (and those of society in many other major cities) closed with Lent, the celebration spread from the South during the Gilded Age and the Four Hundred, as well as everyday New Yorkers, threw a variety of balls and gatherings to mark the occasion.

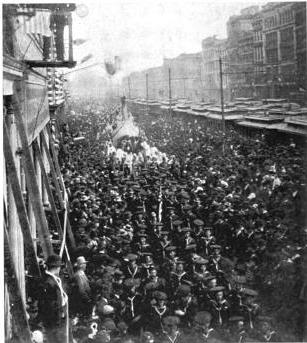

Since Mardi Gras celebrations had begun to distance itself from the Church, it descended into what many longtime residents of the city considered “chaos.” The Mystic Crew, or Crew of Comus was founded in 1857 by six New Orleans businessmen as a secret society which would observe Mardi Gras in a less crude fashion. This society was soon joined by rivals–the Argonauts (1891), Atlanteans (1891), Krewe of Proteus (1881), Momus (1879), and Rex (1880), whose members were also made up of businessmen in high society. With the appearance of these secret societies, and the accompanying exclusive balls, floats and parades, Mardi Gras lost a fair bit of its wildness and openness by the turn of the century.

Nevertheless, the customs of these secret societies became a high point of the celebrations, particularly for women and debutantes, who were selected as maids and Queens for each society’s float. Of most importance was Rex, king of the carnival, who came up the river on his private yacht, which was decked out from stem to stem with many colored flags and was saluted by visiting battleships with twenty-one guns. The local militia would meet “His Majesty” on the landing and a grand military parade would lead Rex to the city hall, where he was presented the keys of the city by the “Duke of Crescent City” (the mayor). In the evening, the Krewe of Comus would throw a ball at the old French Opera house, where “all the kings and their queens, representing all the carnival societies, were in the opening quadrille, all crowned and robed and with their splendid suites.” At midnight, all of the masked men would disappear and return in evening dress, but as they were required to show their invitations, it was impossible to discern whom was masked as who.

Nevertheless, the customs of these secret societies became a high point of the celebrations, particularly for women and debutantes, who were selected as maids and Queens for each society’s float. Of most importance was Rex, king of the carnival, who came up the river on his private yacht, which was decked out from stem to stem with many colored flags and was saluted by visiting battleships with twenty-one guns. The local militia would meet “His Majesty” on the landing and a grand military parade would lead Rex to the city hall, where he was presented the keys of the city by the “Duke of Crescent City” (the mayor). In the evening, the Krewe of Comus would throw a ball at the old French Opera house, where “all the kings and their queens, representing all the carnival societies, were in the opening quadrille, all crowned and robed and with their splendid suites.” At midnight, all of the masked men would disappear and return in evening dress, but as they were required to show their invitations, it was impossible to discern whom was masked as who.

Another old custom was the “King Cake” or gâteau du Rois. Though associated with the festival of Epiphany in the Christmas season, the French and Spanish colonists brought their traditions to the New World and it morphed into a Mardi Gras custom, since the King and Queen of krewes were chosen on King’s Day, or Twelfth Night. The King cake is a ring of twisted bread topped with icing or sugar dyed the traditional Mardi Gras colors of purple, gold, and green, and whomever found the trinket baked within its folds was required to provide the cake for the following year’s celebration.

When the clock struck midnight, it marked the end of Mardi Gras and the beginning of Ash Wednesday, the day of repentance. Many of the celebrations and traditions of Mardi Gras of the 19th century remain, so when you get the chance to visit New Orleans during the festivities you will notice the connection between the present and the past remains strong!

Further Reading:

The Picayune’s Guide to New Orleans (1903 edition)

The Picayune Creole cook book (1922)

Comments are closed.