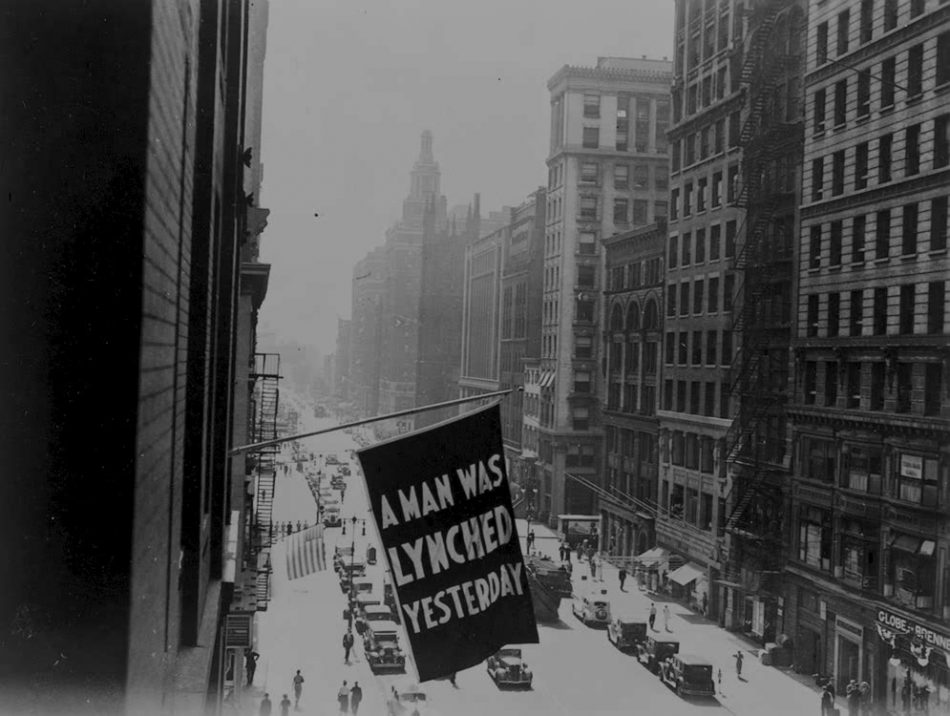

Flag flying above Fifth Avenue, New York City, ca. 1938. Copyprint.

NAACP Collection, Prints and Photographs Division.

Reproduction Number: LC-USZC4-4734/LC-USZ62-33793 (6-10b)

Courtesy of the NAACP

Many would love to believe that life one hundred years ago was gentler, better mannered, and simpler than today. I love history dearly, and I love historic sites, period dramas, and the like. I wouldn’t be working in museums and archives if I didn’t believe in the power of history for truth, reconciliation, justice, and healing.

But the past isn’t the sepia tinted photographs of ancestors or the technicolor images of Downton Abbey. The past, to paraphrase L.P. Hartley, is sometimes a foreign country where they do things differently, but what happened then laid the groundwork for today. And that includes the most horrific, bloody, and unjust every day occurrence in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era: lynching.

James Weldon Johnson labeled the year 1919 as the “Red Summer” because of the extraordinary violence and blood shed as African Americans, many of whom were returning home after serving in WWI, were met by Judge Lynch across most of the United States. The relationship between Americans and extralegal violence dates back to the Revolutionary War, where, according to Robert L. Zangrando, lynchings were “used initially to punish suspected criminals and Tories.” As the practice spread with western expansion across the frontier, it became a regular method of dealing with ” gamblers…antislavery advocates…Native Americans.” After the 1890s, immigrants, political radicals, and others who broke local mores were targets of mob violence. During Reconstruction, lynching became the method of intimidating, terrorizing, and controlling African Americans; the various vigilante groups we often identify as “KKK” expanded in the South on the backs of such violence.

The Gilded Age was in full swing in the 1890s, but so was the increasing use of lynchings to oppress African Americans and halt their attempts to achieve economic, educational, and civic prosperity. Ida B. Wells emerged during this decade as a powerful anti-lynching crusader after the murders of two businessmen friends in Memphis, whose successful grocery store aroused the resentment of their white competition.

OUR country’s national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an “unwritten law” that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal. — “Lynch Law in Americahttps://blackpast.org/1900-ida-b-wells-lynch-law-america,” The Arena 23.1 (January 1900): 15-24.

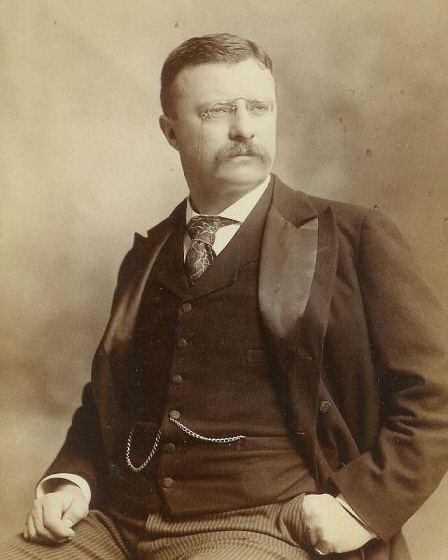

Wells’ activism, the attention of the black press, and various organizations (some made up of white and black members), placed significant pressure on government officials to respond to lynching. Presidents Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt condemned lynching during their administrations, and a number of congressmen attempted to introduce anti-lynching bills between 1884 and the early 1900s, but public sentiment about the cause of lynchings–the threat black men posed to white women–hampered any serious efforts to make them a crime. Even Mark Twain was moved by the violence to pen a lament against lynching in his essay “The United States of Lyncherdom,” but he declined to publish it in his lifetime, declaring “I shouldn’t have even half a friend left down there [in the South], after it issued from the press.”

The NAACP, formed in 1909, increased its membership in the 1910s on the platform of pouring resources and strength by anti-lynching legislation. The appointments of James Weldon Johnson and Walter Francis White focused the organization’s anti-lynching crusade, particularly in the racist, xenophobic atmosphere fostered by D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), whose revisionist history of the Civil War and Reconstruction inspired a new Ku Klux Klan; their targets this time were blacks, Jews, Catholics, and other “undesirables” who undermined good, moral American values.

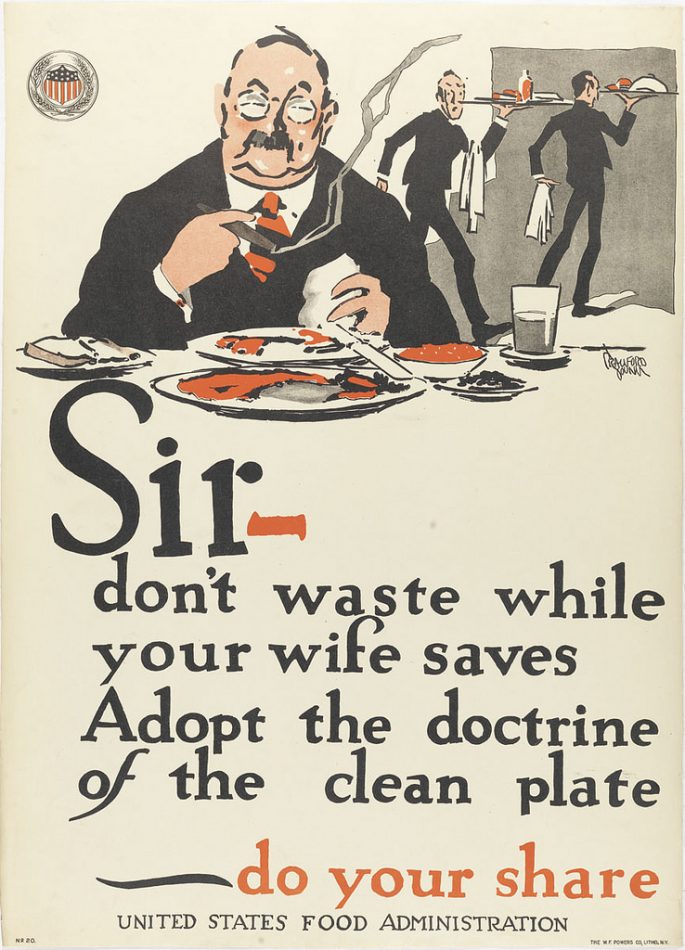

This film only fanned the flames of the general anti-immigrant and anti “hyphenated Americans” anxieties of the WWI era, where many German Americans were interned in camps as alleged German spies, where the government instituted surveillance against African Americans deemed as “unpatriotic,” and mob violence struck East St. Louis in 1917 and in Georgia, where a Jewish American factory superintendent named Leo Frank was lynched after being wrongly convicted of murdering a thirteen year old white female employee.

The Red Summer was only the culmination of an inflamed America. Between April and November, African Americans were lynched and terrorized from coast to coast, with the uprisings in Chicago, Elaine (AK), Knoxville (TN), and Washington DC being the most notable. It is sadly ironic that the NAACP released a book of their investigative research, Thirty Years of Lynching in the United States, 1889-1918, right as the Red Summer began. In it, the NAACP detailed the lynchings of black and white men and women (“78.2 per cent. of the victims were Negroes and 21.8 per cent. white persons”), their geographic location, offenses, and charts of all facts, and included the stories of one hundred lynchings during the period.

NAACP efforts increased in the 1920s, focusing mostly on the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, which was introduced by Rep. Leonidas C. Dyer (R-MO) to Congress during the 1922-24 sessions–and was filibustered by Southern Democrats all three times. By the end of the decade, lynchings had decreased, perhaps because the general prosperity of the Roaring Twenties was a good distraction; however, the Great Depression spurred a renewal of lynchings and the NAACP and their Congressional allies pushed once more for anti-lynching laws. Once again, they were met with failure, as first the New Deal and then WWII ensnared America’s attention. Yet, according to many historians, the fight for anti-lynching inspired significant interracial and inter-class partnerships to rid the United States of this injustice.

Looking back at this period from 2016 reveals that the past isn’t a foreign country–it illuminates and shapes today. And just as the violence touched the lives of the diversity of people who make up the United States then, it remains the same right now, and it takes courageous people, politicians, and organizations to fight for justice.

Further Reading

Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases by Ida B. Wells-Barnett

The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States by Ida B. Wells-Barnett

The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950 by Robert L. Zangrando

Red Summer: The Summer of 1919 and the Awakening of Black America by Cameron McWhirter

On the Laps of Gods: The Red Summer of 1919 and the Struggle for Justice that Remade a Nation by Robert Whitaker

Anti-Racism in 19th Century Britain

‘Terrorism’ of Lynching: See How Nonprofit Collects Soil From Lynching Sites for National Memorial

Good on Presidents Benjamin Harrison, William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt for standing up and being counted, as a time when they were probably running a risk in doing so. Even better, good on the various congressmen who tried to introduce anti-lynching bills at a time when lynching was doing a roaring trade.

Now we have to ask why the murderers, and particularly the mass murderers, were not tried under ordinary murder legislation. So even if anti-lynching bills never got up, did the police and courts not feel they had legislation with which to charge the killers?

Sadly, in many cases I’ve read, the police were either involved in the lynchings or turned a blind eye. Sometimes, a white person (law enforcement or civilian) who attempted to stop the mob violence by hiding the alleged criminal, was threatened themselves. Also, since black people were pretty much barred from testifying against whites, the perpetrators would never be charged.