Many music historians–and historians in general–consider the musical genres that emerged from African-American communities at the turn of the century to be the first authentically “American” style of music. Ragtime, blues, jazz, and the like are also considered the soundtrack of early twentieth century American life, and the combination of the popular press, new technologies like phonographs and the cinema, and the hunger for celebrities, created a perfect storm for the rise of music stars. And female music stars in particular.

The earliest blues music appeared at the turn of the century, in New Orleans, where there was a “cross-pollination of many kinds of music…Marches, French quadrilles, Spanish rhythms, black dance music and of course ragtime.” 1 The work songs, spirituals, and gospel music sung by African-Americans around this period shared similar elements, namely that of “call and response,” and in general, encompassed a wide range of emotions borne from life’s tough, heartbreaking experiences. As black music spread upwards from the Mississippi Delta, with the migration of African-Americans to the Midwest and North, these various elements began to morph away from ragtime and into the two genres soon to be known as the blues and jazz.

In 1914, W. C. Handy recorded the first song that officially set the standard for the blues and its twelve bar, AAB form:

A: I hate to see that evening sun go down

A: I hate to see that evening sun go down

B: Cause my baby, he’s gone left this town

A: I hate to see that evening sun go down

A: I hate to see that evening sun go down

B: Cause my baby, he’s gone left this town

Feelin’ tomorrow like I feel today… 2

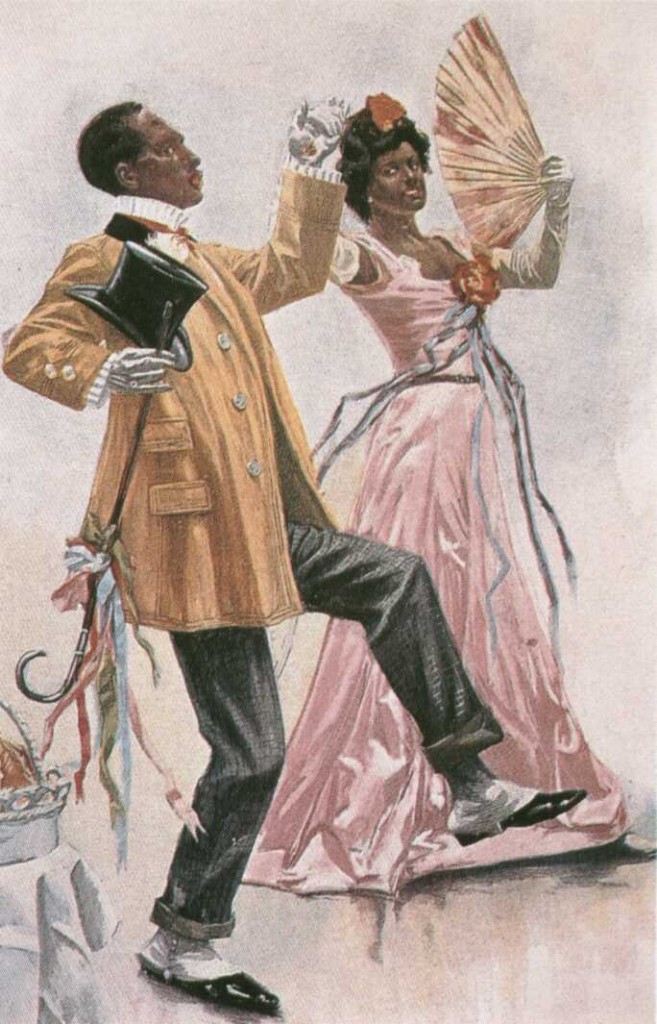

It’s no coincidence that the blues emerged during the nadir of race relations in the United States, and many white audiences reacted to blues (and jazz) with a mix of fascinated revulsion, both because of its roots in the black community and its “low” style in comparison to “high” style music like opera. Mainstream society was also still reeling from other forms of black music, like ragtime and the tango, with their accompanying dances!

According to Angela Y. Davis, in Blues Legacy and Black Feminism, “The historical context within which the blues developed a tradition of openly addressing both female and male sexuality reveals an ideological framework that was specifically African-American. Emerging during the decades following the abolition of slavery, the blues gave musical expression to the new social and sexual realities encountered by African Americans as free women and men. The former slaves’ economic status had not undergone a radical transformation–they were no less impoverished than they had been during slavery. It was the status of their personal relationships that was revolutionalized. For the first time in the history of the African presence in North America, masses of black women and men were in a position to make autonomous decisions regarding the sexual partnerships into which they entered. Sexuality thus was one of the most tangible domains in which emancipation was acted upon and through which its meanings were expressed. Sovereignty in sexual matters marked an important divide between life during slavery and life after emancipation.”

Folkorists attempted to understand and categorize the blues, as seen in this interview with W.C. Handy in 1916:

“Have blues any relation to Negro folksong?” Handy replied instantly, “Yes, they are folk-music.”

“Do you mean in the sense that a song is taken up by many singers who change and adapt it and add to it in accordance with their own mood?” I asked. “That constitutes communal singing in part, at least.”

“I mean that and more,” he responded. “That is true, ol course, of the blues, as I’ll illustrate a little later. But blues are folk-songs in more ways than that. They are essentially racial— the ones that are genuine (though since they became the fashion many blues have been written that are not Negro in character), and they have a basis in older folk-song.”

“A general or a specific basis?” I wished to know.

“Specific,” he answered. “Each one of my blues is based on some old Negro song of the South, some folk-song that I heard from my mammy when I was a child. Something that sticks in my mind, that I hum to myself when I’m not thinking about it. Some old song that is a part of the memories of my childhood and of my race. I can tell you the exact song I used as a basis for any one of my blues. Yes, the blues that are genuine are really folk-songs.”

I asked Handy if the blues were a new musical invention, and he said, “No. They are essentially of our race and our people have been singing like that for many years. But they have been publicly developed and exploited in the last few years. I was the first to publish any of them or to develop this special type by name.” He brought out his Memphis Blues, his first “blues” song, in 1910, he said.

The fact that the blues were a form of folk-singing before Handy published his, is corroborated by various persons who have discussed the matter with me, and in Texas the Negroes have been fond of them for a long time. Early Busby, now a musician in New York, says that the shifts of Negroes working at his father’s brickyard in East Texas years ago, used to sing constantly at their tasks and were particularly fond of the blues.

Handy commented on several points in connection with the blues—for instance, the fact that they are, he says, all in one tone, but with different movements according to the time in which they are written. The theme of this modern folk-music is, according to Handy, the Negro’s emotional feeling apart from the religious. As is well recognized, the Negro normally is a person of strong religious impulse, and the spirituals are famous as expressing his religious moods,—but they do not reveal all his nature. The Negro has longings, regrets, despondencies and hopes that affect him strongly, but are not connected with religion. The blues, therefore, may be said to voice his secular interests and emotions as sincerely as the spirituals do the religious. Handy said that the blues express the Negro’s two-fold nature, the grave and the gay, reveal his ability to appear the opposite of what he is.

“Most white people think that the Negro is always cheerful and lively,” he explained. “But he isn’t, though he can be that way sometimes when he is most troubled in mind. The Negro knows the blues as a state of mind, and that’s why this music has that name.” 3

Around this time, a young Bessie Smith was forming her talents under the wing of Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, an early blues singer who also owned her own theatre troupe. Smith was born one of seven children in Chattanooga, TN in 1894, and was orphaned by age eight. At age nine, “Bessie sang on street corners for nickles…she sang everything, including Baptist hymns.” 4 Her brother Clarence had since run away to the stage and arranged an audition for his sister with Moses Stokes’s travelling show–which is where she met Ma Rainey. Despite Smith’s disadvantages–her voluptuous body, her heavier features, and her darker skin, in a time where black female artists were expected to be “tall, tan, and terrific”–she had an undeniable talent.

Smith’s career rose once she joined the Theater Owners’ Booking Association (TOBA), which was a vaudeville circuit that specialized in booking black talent in the United States’s black theaters. And once she signed with Columbia Records, Smith took control of her own career–a revolutionary decision as an African-American and as a woman. The music industry was in its infancy, and mostly released respectable music and recordings of stage hits. Black musicians were rare, save for extraordinary acts like James Reese Europe and his band (Europe was the musical director for Vernon and Irene Castle before WWI), but this changed with the release of Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues” in 1920.

Smith, no relation to Bessie, ushered in a new dawn for black musicians and the music industry (though, their music was categorized as “race records”). Bessie Smith entered the recording studio, armed with a one year contract and an advance of $1500, and soon released her first hit, “Downhearted Blues.”

The 1920s was Bessie Smith’s era, and she set the bar not only for female blues performers, but for African-Americans in the music industry. By the time of her death in 1937, Smith had released nearly twenty hit records, and directly influenced the career of her contemporaries (Alberta Hunter and Ethel Waters) and a new generation of singers, like Billie Holliday.

Bessie airs on HBO May 16, 2015 at 8 PM.

- Giles Oakley. The Devil’s Music: A History of the Blues (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1976), 33 ↩

- http://www.lyricsmania.com/st_louis_blues_wc_handy,_1914_lyrics_sue_keller.html ↩

- Dorothy Scarborough, “The ‘Blues’ as Folk-Songs,” Publications of the Texas Folklore Society no 2 (1916), 52-66. ↩

- Elaine Feinstein. Bessie Smith (Great Britain: Viking, 1985), 20. ↩

What a fun read! I listen to Billie Holiday but haven’t heard much of Bessie Smith. How cool that Queen Latifah will be playing her!

Thanks! I took an intro to jazz history course last year that deepened my appreciation of Bessie. And I can’t wait to see the biopic! Queen Latifah is sure to be amazing in the role.

I am impressed that once she signed with Columbia Records, Bessie Smith took control of her own career. Not only would that have been almost impossible for an African-American and a woman, I imagine it would have been very difficult for any singer without truck loads of independent income. Did she have an agent to help look after her interests? Were her legal rights protected?

At the beginning of her recording career, Bessie’s husband played a role in hounding the label for better terms, but most of her ability to take control was learned while watching Ma Rainey.

Did you ever see The Butcher’s Wife? That’s where I first hard of Bessie Smith.

No, what’s that?

It’s a romcom starring Jeff Daniels and Demi Moore.

oooh sounds good. Going to look it up. Thanks!