When the dog days of summer come around, the prospect of relaxing and playing on beautiful beaches is highly anticipated. The laws of “Jim Crow” (the colloquial name for the dizzying array of prohibitions and restrictions placed on black and white interaction from roughly 1896 to 1954/1964) meant that African Americans were often barred from enjoying their summers in the same manner as European Americans. In a slightly ironic twist, before Jim Crow laws hardened race relations and created a permanent color line, according to Andrew W. Kahrl in The Land Was Ours, distinguished African Americans “purchased cottages and established close-knit summer colonies in many of the popular summer destinations in the Northeast and mid-Atlantic states, including, among others, Saratoga, New York; Cape May, New Jersey; and Harpers Ferry, West Virginia.” 1 There was also a significant year-round population of African Americans at popular Gilded Age summer resorts, as evidenced by the Gilded Age Newport in Color website. From the 1890s to the 1960s, the resorts that sprang up along the coastlines of the United States provided a haven against racism and humiliation, created multi-generational memories, and tell a story of how landscapes and leisure can be used to combat oppression!

Highland Beach, Maryland

It was the sudden hardening of the color line that influenced Charles Douglass, youngest son of Frederick Douglass, to found Highland Beach in 1893. Charles and his wife Fannie were barred from vacationing on a Chesapeake Bay resort and as they walked along a shoreline, they came across a black-owned farm. The owner sold them forty acres and Douglass divided the land into lots, which he sold to friends. “Twin Oaks,” the Queen Anne house Douglass built for his father, who died before its completion, is now The Frederick Douglass Museum and Cultural Center. Other nearby African American enclaves included the villages of Arundel-on-the-Bay and Oyster Harbor.

Oak Bluffs, Martha’s Vineyard (Massachusetts)

The African American presence on Martha’s Vineyard stretches back to the mid-18th century, according to Jill Nelson in her family memoir/history book Finding Martha’s Vineyard. The area known as Oak Bluffs was originally a Methodist revival camp; by the turn-of-the-century, African American Yankees were a significant presence in this corner of the island, whether they were business-owners or pleasure-seekers. The official period of African American leisure began in 1903 when Charles Shearer, a teacher born enslaved in 1854, purchased a cottage near the Baptist church where he and his family worshiped. His wife Henrietta started a laundry to supplement the family’s income, which she ran until her death in 1917. The Shearer daughters converted the former laundry into a guest house and inn for African American vacationers–Shearer Cottage–which still operates today.

Sag Harbor, Long Island (New York)

As with Martha’s Vineyard, the African American presence on Long Island stretches back to the days of slavery. The Zion A.M.E. Church established in 1840 was even a stop on the Underground Railroad! They heyday of Sag Harbor began in the late 1920s, when prominent African American New Yorkers (re)discovered the comforts of the coast during the hot summer months. 2 The communities of Azurest, Sag Harbor, and Ninevah flourished between 1948 and 1955, when Maud Terry of Queens, NYC purchased property in Azurest and sold lots to friends. Other wealthy African Americans soon followed, and soon this became the hidden secret of the Hamptons!

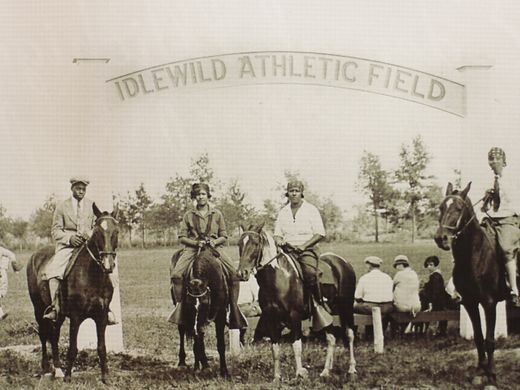

Idlewild, Michigan

Beautiful Idlewild. Black Eden. Those were some of the names bestowed upon this incredible summer resort in the wilds of Western Michigan. Founded in 1912 by white investors who sold lots to the black elite in Chicago and Detroit (and later from all parts of the United States), it quickly became the place to be for doctors, lawyers, and the brightest stars of the 20th century, from Cab Calloway to Dinah Washington during its heyday in the 1940s-60s. The average Idlewilders took advantage of the lush beach and the gorgeous forest, taking part in hunting and fishing, as well as athletics.

American Beach, Florida

Further Reading

An American Beach for African Americans by Marsha Dean Phelts

Chowan Beach: Remembering an African American Resort by Frank Stephenson

Black Eden: The Idlewild Community by Lewis Walker

Links

Eastville Community Historical Society

American Beach Museum

Shearer Cottage

Idlewild African American Chamber of Commerce