There arose in the 1880s, the phenomena of the “professional beauty.” A curious phase had come over society wherein publicity became the fashion, and from it, the craze to exhibit photographs of “Ladies of Quality” in the windows of Fleet Street. Instrumental in creating this sensation was London-based artist Frank Miles, who specialized in watercolors of society women, and Lillie Langtry.

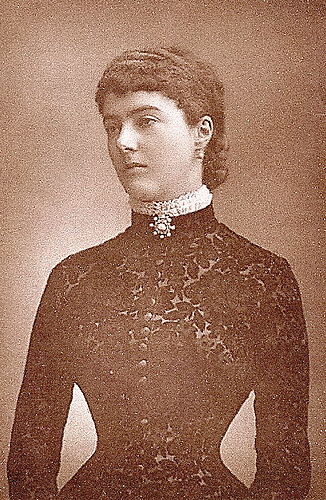

Born on the Isle of Jersey, she arrived in London in the mid-1870s with her alcoholic husband Edward Langtry and promptly entered society despite having little money. While her beauty at first created a mild interest, it was her attendance of social events clad in the same black dress that created a stir. When someone finally commented on her continuous use of that dress, she arrived at her next engagement wearing a white dress of similar fashion. This provocation created a furor and suddenly, artists wanted to paint her, hostesses vied to have her on their guest lists, and people (even the most fearsome dowagers!) even stood on benches in Hyde Park, or chairs at balls, to catch a glimpse of her. So great was her fame that her greatest wish–to be presented to Queen Victoria–was granted (some say at the instigation of the queen herself!). Coached by the highest in the land (the Prince of Wales, soon her lover), the wittiest (Oscar Wilde), and the most talented (James MacNeil Whistler), she cut a swath through aristocratic society. Frank Miles, one Lillie’s earliest acquaintances, capitalized on the increasing voraciousness of people for pictures of society beauties, and these women, subsequently dubbed “Professional Beauties” or, P.B.’s for short, took not only London at large by storm, but the known world.

Born on the Isle of Jersey, she arrived in London in the mid-1870s with her alcoholic husband Edward Langtry and promptly entered society despite having little money. While her beauty at first created a mild interest, it was her attendance of social events clad in the same black dress that created a stir. When someone finally commented on her continuous use of that dress, she arrived at her next engagement wearing a white dress of similar fashion. This provocation created a furor and suddenly, artists wanted to paint her, hostesses vied to have her on their guest lists, and people (even the most fearsome dowagers!) even stood on benches in Hyde Park, or chairs at balls, to catch a glimpse of her. So great was her fame that her greatest wish–to be presented to Queen Victoria–was granted (some say at the instigation of the queen herself!). Coached by the highest in the land (the Prince of Wales, soon her lover), the wittiest (Oscar Wilde), and the most talented (James MacNeil Whistler), she cut a swath through aristocratic society. Frank Miles, one Lillie’s earliest acquaintances, capitalized on the increasing voraciousness of people for pictures of society beauties, and these women, subsequently dubbed “Professional Beauties” or, P.B.’s for short, took not only London at large by storm, but the known world.

Just about any beautiful woman could become a professional beauty–not through success at court, but in the emerging celebrity culture associated with illustrated periodicals and mass-circulated photographs. The professional beauty needed not be rich, highly born, nor well educated–provided she had sense enough to escape from committing any glaring missteps–all that was required of her was that her face should be approved by society as a great beauty and her future was assured. Recognition as a P.B. was reward in itself. Reproductions of the beauties appeared in every store window and hung in every middle-class dwelling. The originals graced the mansions of wealthy patrons of the arts. Queen Victoria ‘s youngest son, Prince Leopold, became so enamored of a pen-and-ink sketch of Lillie Langtry he had seen while visiting Miles’s studio that he acquired it to hang in his bedchamber – until his mother snatched it down.

Just about any beautiful woman could become a professional beauty–not through success at court, but in the emerging celebrity culture associated with illustrated periodicals and mass-circulated photographs. The professional beauty needed not be rich, highly born, nor well educated–provided she had sense enough to escape from committing any glaring missteps–all that was required of her was that her face should be approved by society as a great beauty and her future was assured. Recognition as a P.B. was reward in itself. Reproductions of the beauties appeared in every store window and hung in every middle-class dwelling. The originals graced the mansions of wealthy patrons of the arts. Queen Victoria ‘s youngest son, Prince Leopold, became so enamored of a pen-and-ink sketch of Lillie Langtry he had seen while visiting Miles’s studio that he acquired it to hang in his bedchamber – until his mother snatched it down.

Women of superior social stations inundated the P.B. with cards for dinners and receptions; for a time no party was considered complete or successful without these ladies. People would receive invitations with “Do come, the P.B. s will be there,” and this meant the certain attendance of society. Artists vied with each other in inviting her to their studios in the hope that they would be permitted to paint or sketch her. The professional beauty need never purchase clothing or accessories again; all that was required of her was the murmur of her couturier’s or milliner’s names to guarantee instant success of that artist of fashion. “She was worth – literally – 100 paying customers. She was a walking – no a gliding – advertisement.”

Women of superior social stations inundated the P.B. with cards for dinners and receptions; for a time no party was considered complete or successful without these ladies. People would receive invitations with “Do come, the P.B. s will be there,” and this meant the certain attendance of society. Artists vied with each other in inviting her to their studios in the hope that they would be permitted to paint or sketch her. The professional beauty need never purchase clothing or accessories again; all that was required of her was the murmur of her couturier’s or milliner’s names to guarantee instant success of that artist of fashion. “She was worth – literally – 100 paying customers. She was a walking – no a gliding – advertisement.”

In London, the professional beauty was queen. Not a ball was considered a success without her presence. At dinner she eclipsed rank wealth and fame and was the object of attentions which would be flattering were they less curious and obtrusive. Should she ride in the Row a little cavalcade accompanied her, which only quit her presence when some very distinguished personage came up to canter by her side. At a country house party, no matter who may be the visiting, she was always the most favored of guests. So firmly did the professional beauty rule society that her word was law and her wishes commanded the amusement of the hour: If she voted guessing acrostics dull, acrostics were abandoned. If she was fond of hunting, the best and safest of mounts that the stables possessed were placed at her disposal, whilst the most sober and careful of grooms was to specially attend upon her and to see that her exquisite beauty should not for a moment be in danger.

In London, the professional beauty was queen. Not a ball was considered a success without her presence. At dinner she eclipsed rank wealth and fame and was the object of attentions which would be flattering were they less curious and obtrusive. Should she ride in the Row a little cavalcade accompanied her, which only quit her presence when some very distinguished personage came up to canter by her side. At a country house party, no matter who may be the visiting, she was always the most favored of guests. So firmly did the professional beauty rule society that her word was law and her wishes commanded the amusement of the hour: If she voted guessing acrostics dull, acrostics were abandoned. If she was fond of hunting, the best and safest of mounts that the stables possessed were placed at her disposal, whilst the most sober and careful of grooms was to specially attend upon her and to see that her exquisite beauty should not for a moment be in danger.

A fierce war of opinion as to their rival merits raged about them. Artists extolled Mrs. Langtry’s classical Greek profile golden hair and wonderful column-like throat, graced with the three plis de Venus, which made her an ideal subject for their brushes and chisels. Poems were written in celebration of the professional beauty, one of which was saved by Lady Randolph Churchill, herself a professional beauty:

First Lady Dudley did my sense enthral,

Whiter than chisel’d marble standing there,

The Juno of our earth “divinely tall,

And most divinely fair.”And next with all her wealth of hair unroll’d,

Was Lady Mandeville bright eyed and witty;

And Miss Yznaga whose dark cheek recall’d

Lord Byron’s Spanish ditty.The Lady Castlereagh held court near by,

A very Venus goddess fair of love,

And Lady Florence Chaplin nestled nigh,

Gentle as Venus doveAs gipsy dark with black eyes like sloes,

A foil for Violet Lindsay sweetly fair,

Stood Mrs Murietta a red rose,

Was blushing in her hair.And warmly beautiful like sun at noon,

Glowed with love’s flames our dear Princess Louise,

Attended by the beautiful Sassoon,

The charming Viennese!Then Lady Randolph Churchill, whose sweet tones

Make her the Saint Cecilia of the day;

And next those fay-like girls, the Livingstones,

Girofla Giroflé!And then my eyes were moved to gaze upon

The phantom like celestial form and face

Of the ethereal Lady Clarendon,

The loveliest of her raceThe beauteous sister of a Countess fair,

Is she the next that my whole soul absorbs,

A model she for Phidias, I declare,

The classic Lady Forbes

Other preeminent professional beauties were Lady Lonsdale (afterwards Lady de Grey), Lady Brooke (later Lady Warwick), the Duchess of Leinster and her sister Lady Helen Vincent, Lady Londonderry, Lady Dalhousie, Lady Ormonde, Lady Mary Mill, Lady Gerard, Mrs. Luke Wheeler, who always “appeared in black,” and Mrs. Cornwallis West, the mother of Lady Randolph Churchill’s much younger second husband.

Other preeminent professional beauties were Lady Lonsdale (afterwards Lady de Grey), Lady Brooke (later Lady Warwick), the Duchess of Leinster and her sister Lady Helen Vincent, Lady Londonderry, Lady Dalhousie, Lady Ormonde, Lady Mary Mill, Lady Gerard, Mrs. Luke Wheeler, who always “appeared in black,” and Mrs. Cornwallis West, the mother of Lady Randolph Churchill’s much younger second husband.  Accordingly, and some say, obviously, many of these women reigned briefly as the Prince of Wales’s mistress. In direct contrast to these London beauties, the professional beauties of Paris were not ranked or cataloged. They did not have their portraits published in the illustrated papers nor did they allow their photographs to be sold at the stationers. However there always existed a little staff of about twenty women who represented grace, beauty and Parisian elegance.

Accordingly, and some say, obviously, many of these women reigned briefly as the Prince of Wales’s mistress. In direct contrast to these London beauties, the professional beauties of Paris were not ranked or cataloged. They did not have their portraits published in the illustrated papers nor did they allow their photographs to be sold at the stationers. However there always existed a little staff of about twenty women who represented grace, beauty and Parisian elegance.

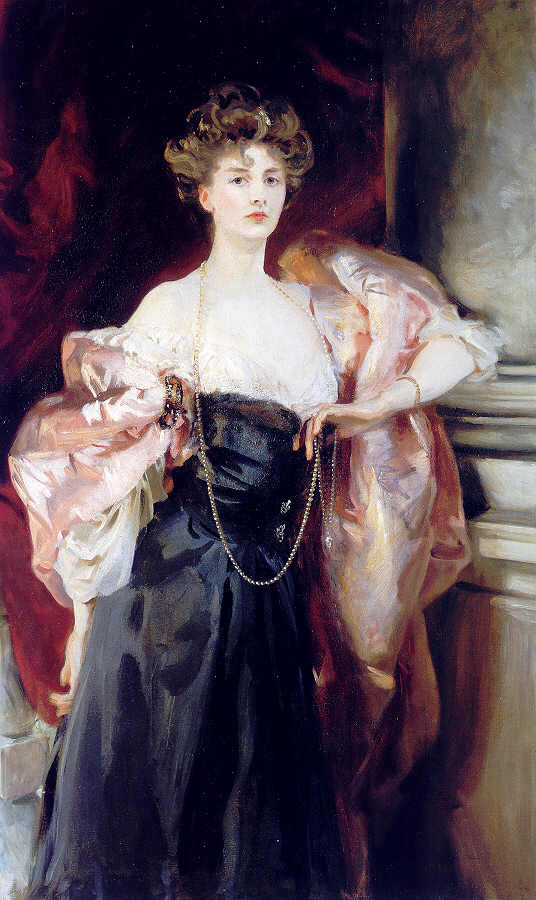

But one Parisian hostess did break the mold: Virginie Amélie Gautreau, who is better known to history as the subject of John Singer Sargent’s “Portrait of Madame X.” An American expatriate married to a wealthy French banker, when her painting was revealed in the Paris Salon of 1884, it caused a scandal. Already trailed by whispers of fast behavior, the portrait as painted, was of a sexually-aggressive woman clad in a figure-hugging black gown whose right strap had fallen–a hint that with “one more struggle“, wrote a critic in Le Figaro, “...the lady will be free“. Amidst the outrage and ruination of his career, Sargent painted over the strap to secure it on Madame Gautreau’s shoulder and concealed the painting for over thirty years. As for the lady, her reputation was destroyed and she passed the remaining years of her life alternately attempting to recapture her fame and escaping the realities of time by avoiding mirrors.

But one Parisian hostess did break the mold: Virginie Amélie Gautreau, who is better known to history as the subject of John Singer Sargent’s “Portrait of Madame X.” An American expatriate married to a wealthy French banker, when her painting was revealed in the Paris Salon of 1884, it caused a scandal. Already trailed by whispers of fast behavior, the portrait as painted, was of a sexually-aggressive woman clad in a figure-hugging black gown whose right strap had fallen–a hint that with “one more struggle“, wrote a critic in Le Figaro, “...the lady will be free“. Amidst the outrage and ruination of his career, Sargent painted over the strap to secure it on Madame Gautreau’s shoulder and concealed the painting for over thirty years. As for the lady, her reputation was destroyed and she passed the remaining years of her life alternately attempting to recapture her fame and escaping the realities of time by avoiding mirrors.

The professional beauty’s American counterpart was found in the “Gibson Girl” of the 1890s and 1900s, as created by Charles Dana Gibson. The Gibson Girl set the first national standard for a feminine beauty ideal: “She was taller than the other women currently seen in the pages of magazines.. infinitely more spirited and independent, yet altogether feminine. She appeared in a stiff shirtwaist, her soft hair piled into a chignon, topped by a big plumed hat. Her flowing skirt was hiked up in back with just a hint of a bustle. She was poised and patrician. Though always well bred, there often lurked a flash of mischief in her eyes.”

The professional beauty’s American counterpart was found in the “Gibson Girl” of the 1890s and 1900s, as created by Charles Dana Gibson. The Gibson Girl set the first national standard for a feminine beauty ideal: “She was taller than the other women currently seen in the pages of magazines.. infinitely more spirited and independent, yet altogether feminine. She appeared in a stiff shirtwaist, her soft hair piled into a chignon, topped by a big plumed hat. Her flowing skirt was hiked up in back with just a hint of a bustle. She was poised and patrician. Though always well bred, there often lurked a flash of mischief in her eyes.”  The Gibson Girl appeared on saucers, ashtrays, tablecloths, pillow covers, chair covers, souvenir spoons, screens, fans, umbrella stands and was personified by Gibson’s wife, Irene Langhorne, Evelyn Nesbit and the Danish-American stage actress, Camille Clifford, whose towering coiffure and long, elegant gowns wrapped around her hourglass figure and tightly corseted wasp waist defined the style. Depicted as an equal and sometimes teasing companion to men, the Gibson Girl was provocative and independent, perfectly expressing the cool exuberance of the turn-of-the-century American lady.

The Gibson Girl appeared on saucers, ashtrays, tablecloths, pillow covers, chair covers, souvenir spoons, screens, fans, umbrella stands and was personified by Gibson’s wife, Irene Langhorne, Evelyn Nesbit and the Danish-American stage actress, Camille Clifford, whose towering coiffure and long, elegant gowns wrapped around her hourglass figure and tightly corseted wasp waist defined the style. Depicted as an equal and sometimes teasing companion to men, the Gibson Girl was provocative and independent, perfectly expressing the cool exuberance of the turn-of-the-century American lady.

The life of a professional beauty could be wonderful, exhilarating and fun, but only on the condition that she remained beautiful and charming, had not a hairsbreadth of scandal attached to her name, and could financially maintain her socializing. This was near impossible not only because of her attachment to the spendthrift and frivolous Marlborough House Set, but also the passing of time. Lillie Langtry fell from grace when she bore a child out of wedlock, and only recaptured a bit of her fascination by becoming a moderately talented actress. Even aristocratic women found it difficult to escape the fate of chance: Lady Randolph Churchill was plagued with money troubles all of her life and Daisy Warwick, her family fortune run dry by the 1910s, attempted to blackmail George V into granting her renumeration for her amusement of his deceased father by threatening to publish the letters he exchanged with her during their relationship.

The life of a professional beauty could be wonderful, exhilarating and fun, but only on the condition that she remained beautiful and charming, had not a hairsbreadth of scandal attached to her name, and could financially maintain her socializing. This was near impossible not only because of her attachment to the spendthrift and frivolous Marlborough House Set, but also the passing of time. Lillie Langtry fell from grace when she bore a child out of wedlock, and only recaptured a bit of her fascination by becoming a moderately talented actress. Even aristocratic women found it difficult to escape the fate of chance: Lady Randolph Churchill was plagued with money troubles all of her life and Daisy Warwick, her family fortune run dry by the 1910s, attempted to blackmail George V into granting her renumeration for her amusement of his deceased father by threatening to publish the letters he exchanged with her during their relationship.

Truly only a step above a courtesan, the professional beauty was protected from scandal and the taint of sexual immorality by her rank and marriage. But in a time where women could be considered property (though this lessened considerably by the 1880s in comparison to earlier eras), and her social roles were defined and the boundaries between “public” and “private” were beginning to blur, the P.B. could essentially have the best of both worlds: the fame and fascination of an actress and the venerated social status of an aristocrat.

Sources:

Days I Knew by Lillie Langtry

The Reminiscences of Lady Randolph Churchill by Mrs. George Cornwallis-West

The Edwardian Woman by Duncan Crow

Strapless: John Singer Sargent and the Fall of Madame X by Deborah Davis

London Society by eds Hogg, James and Marryat, Florence.

Edward and the Edwardians by Philippe Jullian

Wonderful post. I first heard the term Professonal Beauty while watching Lillie with Francesca Annis back in 9th Grade.