My upcoming book, Sugar Moon, will be firmly rooted in history that I believe every American should know: the ambush of a company of American soldiers on September 28, 1901, in Balangiga, Philippines. Most people have never heard of it. What happened that day in Balangiga—and in the months of American counterattacks afterward—has been overshadowed by other towns that Americans do know, ones with names like My Lai and Fallujah. Had we learned the lesson of Balangiga, though, these two towns in Vietnam and Iraq might never have hit the headlines. In fact, they might not be noteworthy at all.

How did I stumble upon Balangiga? When I started plotting my story about an American schoolteacher and a Filipino sugar baron—the story that became Under the Sugar Sun—I did a lot of research at Ateneo de Manila University, where I read through old issues of the Manila Times on microfiche. (By the way, if you want to entertain me, give me two rolls of that microfiche and leave me there all day. It’s like giving a child an iPad. History is my babysitter.) One of the articles I stumbled across was entitled: “Sister Hunting for Brother: His Name is E.L. Evans and He is Supposed to Be in the Philippines.” From there, I conjured up the idea of a missing brother to bring Georgina Potter to the Philippines. Yes, she was hired by the American colonial government to start a school in the Visayas, but her real motive in coming—and for letting herself get entangled with a jerk named Archie—was finding her brother, Ben Potter.

Why was Ben missing? Maybe because he was in a significant battle? Or, at least, a very confusing one? In Under the Sugar Sun, Georgina goes to Army Headquarters in Fort Santiago in Manila to find out, and she lays out all the news articles from a battle in Balangiga. A clerk tries to help her, to no avail:

“Your brother should be in here one way or another.” The clerk put his finger on the article with the list. “Name and rank?”

If it were that easy, she thought, she would not have bothered crossing the Pacific. “Sergeant Benjamin Potter.”

“I see a Ben Cutter,” the clerk said. “That’s probably him.” He sounded sure, as if the Army made such mistakes all the time. Maybe they did. He would know.

Georgie pulled another article to compare side by side. “Half the names are spelled differently from one day to another,” she explained. “Cutter one day, then Carter, then Palmer. And here all of the Boston soldiers are described as dead. All of them! My mother and I bought every paper, every edition, for a month, trying to find a new official list that made any sense. And you know what the Army told us? Nothing! No telegram, no letter, nothing.” She was not normally one to create a scene, but she had come a long way for the truth, and she was going to get it.

The confusion of names and numbers really did happen, which is one of the reasons why I chose this setting for my character. It makes sense that if he survived, he still might not want to be found. Several survivors stayed in the Philippines afterward, much to the chagrin of their families.

So, it was decided: Ben served in Company C, Ninth Infantry, which saw action in China during the Boxer War, and then returned to the Philippines to be stationed in Balangiga. Poor Ben. Poor Balangiga.

Company C occupied this town, and occupation is ugly. It doesn’t matter how you justify it—in this case, blockading the southern coast of Samar so that the guerrillas in the mountains could not be resupplied, a legitimate military purpose. It also doesn’t matter if the occupation starts off peacefully, which it did in Balangiga. It is not going to stay that way. The lesson of occupation throughout world history—no matter whether we are talking about ancient Greek occupation of Jerusalem, Israeli occupation of Lebanon, the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, or the American occupation of the Philippines—things will go downhill.

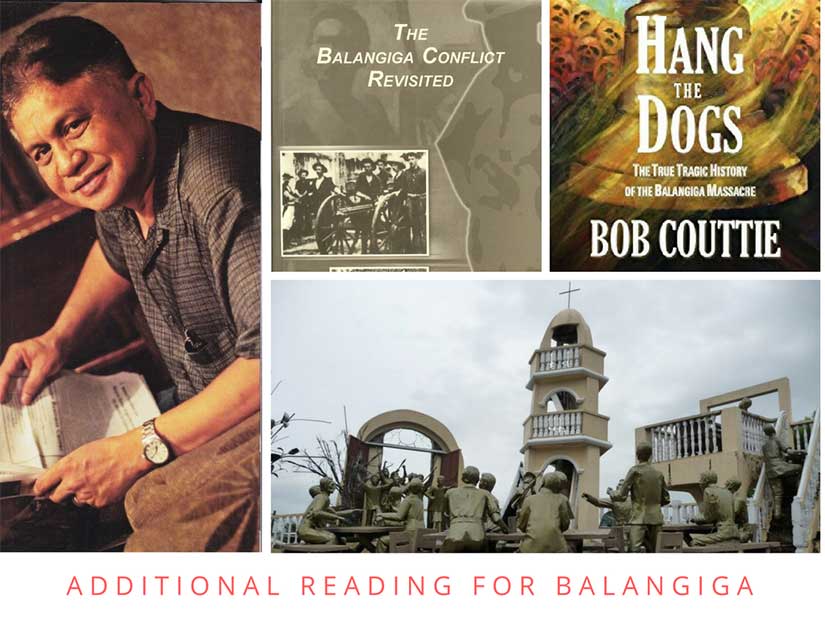

The Americans called the Filipino guerrillas insurrectionists, and they labeled what happened in Balangiga a massacre, implying that the perpetrators had no just cause. On the other side, Filipinos call their soldiers revolutionaries, and they see the event itself as a just uprising. If you want to avoid all judgment, it was an incident, or more specifically an ambush. I am greatly indebted to Philippine historian Rolando O. Borrinaga and British writer Bob Couttie for their first-hand research and outstanding work on Balangiga. In my version of the story, I have taken some liberties—merging characters to simplify things for the reader, renaming a few people—but I hope that my unwitting mentors will find that I got the big brush strokes right. All errors are my own, of course.

As we will see in Sugar Moon, at first things went okay. Uneasily, but okay. An American officer played chess with the parish priest. The man Sergeant Benjamin Potter is based on studied martial arts with the police chief. Individuals got along. But here’s the rub: if the townspeople became too friendly with the Americans, they would face retribution from the revolutionaries up in the mountains. So the town tried to play it cool, stay neutral.

But the Americans noticed some strange things happening—like sweet potatoes planted in the jungle for the guerrilla soldiers, or townspeople not cutting down banana trees that could provide the guerrillas cover—and the Yanks thought they had been betrayed. They ordered the town to cut down essential food sources, to “clean up” the town. If the town complied, not only would they need to destroy their own property, they would also endanger the understanding they had with guerrillas. I think you probably see where this is going. The reality of a town like this during occupation is that it will be caught in between two armies, and if neither army can truly protect the civilians against the other, the people must try to play one off the other. That is a dangerous game.

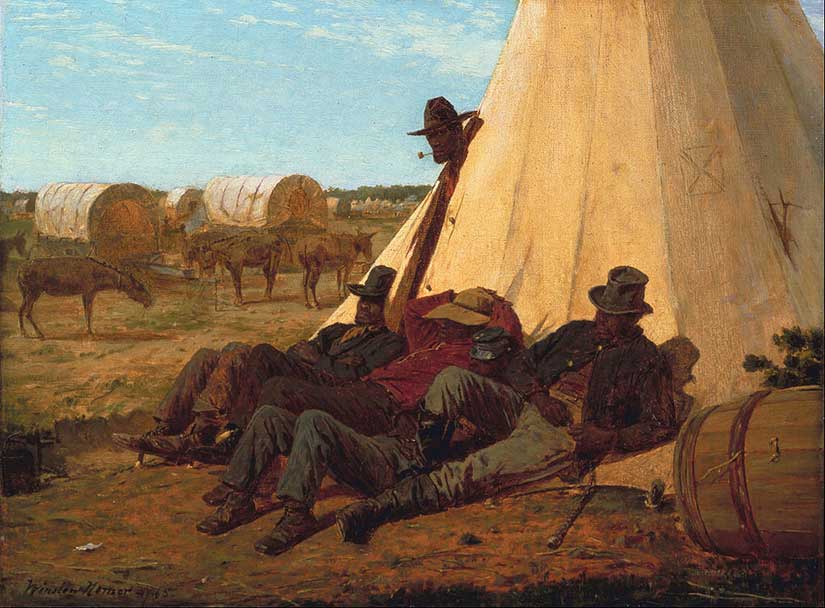

Company C doubled down. They imprisoned the town’s men in conical tents that looked like Native American teepees. These Sibley tents were supposed to sleep 16, but were each jammed full with over 70 men and boys, who had to sit on their haunches all night. They were not fed dinner, and in the morning they were forced to cut down the food their families depended on. This went on for several days.

The Americans did not see the town turning against them. They only saw their own frustration: they felt alone, vulnerable, on the edge of a hostile island, a day’s travel away from the nearest garrison. Yet they did not expect the ambush. My character Ben will narrate the whole debacle through his flashbacks, which starts with him trying to court a local woman. He’s a proper gentleman, don’t worry, but he’s smitten. This, by the way, is based on a real possible romance between an American sergeant and the local prayer leader of the town.

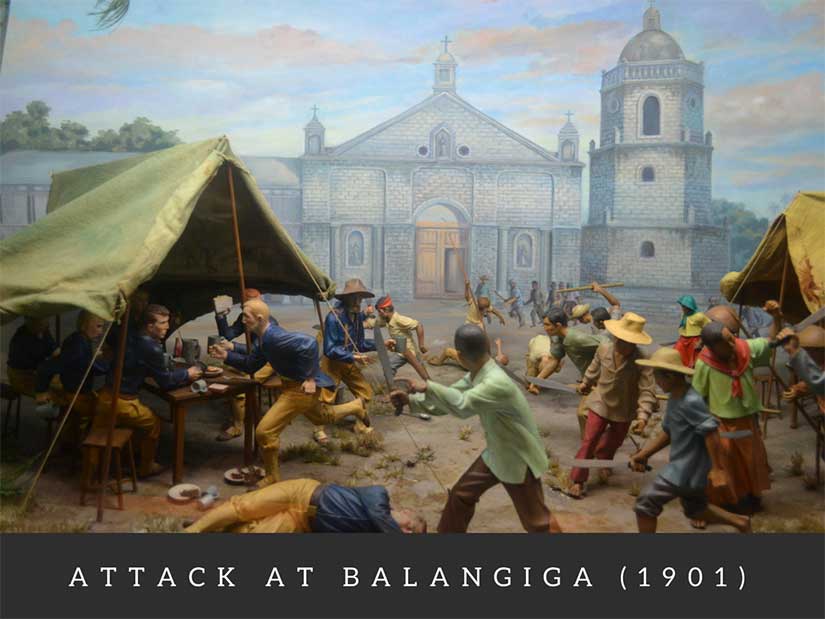

On Sunday, September 28, 1901, the morning after the town fiesta, a church bell rang. Nothing unusual about that—until men dressed as women streamed out of the church with machetes. The American soldiers were eating breakfast. Dozens would die immediately and gruesomely. A little more than half would manage to escape, but several of them would die along the way of their wounds or from other attacks. In total, 48 of 77 Americans would die.

Americans blamed the Filipino revolutionaries for streaming out of the jungle to attack the town, but the truth Borrinaga and Couttie uncovered is that the town actually planned the attack themselves. They may have borrowed some men from villages outside Balangiga proper, and they may have coordinated with the revolutionaries, but this was a town fighting back against the soldiers who had imprisoned them.

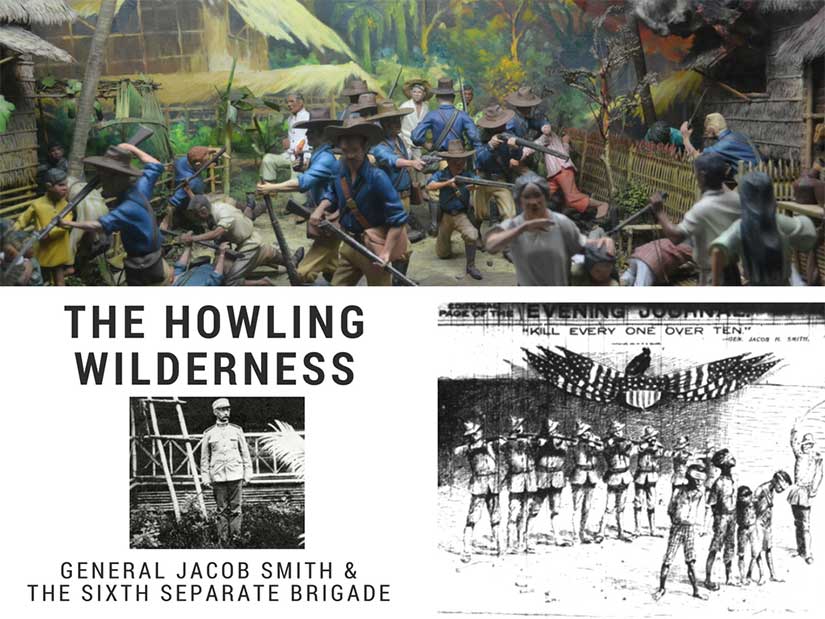

After that, all hell broke loose. If there is something more violent than the rising up of an occupied people, it is the revenge exacted by a conventional military force armed to the teeth. The American commander in Samar ordered his men to turn the entire island into “a howling wilderness” by striking down all men and boys capable of carrying arms, which he defined as all those over ten years old. (That’s not legal, by the way.) His men made a special trip back to Balangiga to burn down the town and kill anyone in sight. Months of revenge resulted in the deaths of thousands on Samar, maybe as many as 15,000, according to Borrinaga.

This was the My Lai moment of the Philippine-American War, and it was just as explosive to the American public as that incident in Vietnam was. For the first time, with the advent of the trans-Pacific telegraph cable, the American public could follow events with an immediacy that had been previously impossible. The excesses of the Army now blanketed newspapers and magazines Stateside. Though military authorities tried to censor the press by controlling the telegraph lines out of Manila, reporters got around this by traveling to Hong Kong to wire their stories. The courts-martial of several American officers made daily headlines, and Senate hearings began on the issue of American atrocities in the Philippines.

But how do you criticize the methods of occupation without questioning the whole endeavor to begin with? You can blame a few “bad apples” to satisfy the public, but is it enough? The general in Samar received a slap on the wrist from the court-martial that followed, and though popular outcry in the US later forced President Roosevelt to demand the general’s retirement, the punishment still didn’t fit the crime. The general retired with a full pension. The American lieutenant in command at My Lai, convicted of murdering 22 Vietnamese civilians, served only seven months of house arrest and then was pardoned.

My character Ben tried hard to be better than the rest, but what happened in Balangiga tortures him. You are not supposed to have liked him in Under the Sugar Sun, and he does not like himself much, either. He suffers from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, something that two of my very best friends share with him. Soldiers with PTSD struggle with guilt, depression, substance abuse, anger management, insomnia, and other health problems. I am greatly indebted to these friends for letting me put some of their worst fears on the page. I hope they will also appreciate the redemptive journey Ben goes through and the healing power of love that he finds. They would tell me this is far too simplistic a cure, but I think they want Ben to have a happily-ever-after, so it’s okay.

George Santayana wrote in 1905: “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” It is fitting he said so at the outset of what was later called the American Century. The vigorous debate about the use of military force abroad—and it’s aftereffects like PTSD—are familiar to people today. But they were not really a part of American discourse until the Philippine-American War. America’s professional army was born out of this war. Before 1898, the entire US Army was smaller than today’s New York City Police Department. Most of the Spanish-American War had to be fought with state volunteers whose enlistments lasted only a year. When hostilities broke out in Philippines, Congress promptly doubled the size of the regular army once, and then doubled it again. For the first time in its history, America had a significant standing army stationed far from its borders. And yet no one learned from Balangiga.

Maybe it is not good enough to just remember the past. You should experience it yourself. That’s the garden where empathy grows. That’s where you get all the feels. I hope Sugar Moon helps.

This essay is cross-posted at my own website under the title: Sugar Sun series location #7: Balangiga.