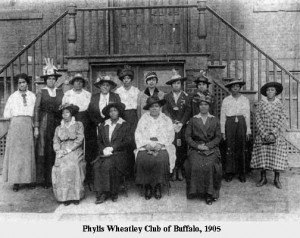

In the late nineteenth century, feminism, suffrage, political action, self-culture and self-help devolved in the women’s club movement, which enjoyed a heyday from the 1890s through the 1920s. Though this movement transformed the lives of upper- and middle-class women of all ethnicities, it made a particular impact on African-American women.

In the late nineteenth century, feminism, suffrage, political action, self-culture and self-help devolved in the women’s club movement, which enjoyed a heyday from the 1890s through the 1920s. Though this movement transformed the lives of upper- and middle-class women of all ethnicities, it made a particular impact on African-American women.

The club movement grew out of the literary and self-improvement groups nicknamed “universities for middle-aged women,” which filled the need for continued learning for women denied a college education after the Civil War. For black women, these groups manifested themselves in two-fold: one, a desire to emulate their white upper- and middle-class counterparts, and two, an outlet to express their frustration over the issue of being black and female. The widely held view of black women at this time was of inherent immorality and promiscuity, which, according to Fannie Barrier Williams, was held equally by whites and black men. Black women of the Progressive Era, feeling that they did not “bask in the sunlight of man’s chivalry, admiration, and even worship,” pointed to Martin R. Delany’s 1852 treatise, The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, which stressed that “no people are ever elevated above the condition of their females.”

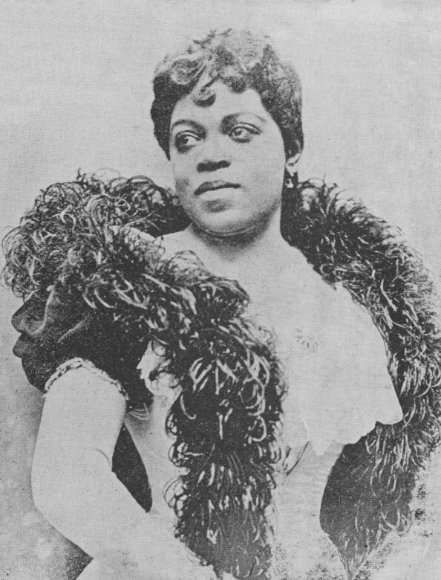

The movement turned from social and literary pursuits to social justice and activism in the 1890s with the demise of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow, which killed any idea held by the black elite that their conduct and class would convince whites that blacks could be their equals. The 1890s was also the era of lynchings, and the decade was characterized by the watershed of blood staining the soil of the South (not only black Southerners, but Jewish Southerners, Italians, etc). Out of this violence came Ida B. Wells, a journalist who gained fame in the mid-1880s when she refused to give up her train seat to a white man and move to a Jim Crow car. Wells was dragged from the train, but she immediately hired a lawyer to sue the railroad company. She won her case in 1884, and received a settlement of $500. Though the railroad appealed the case, Wells earned a reputation as a powerful voice against racism and oppression. By the 1890s, Wells anti-lynching crusade was taken up by the various women’s clubs across the nation, and that issue, along with women’s suffrage, became the platforms upon which the National Association of Colored Women was founded in 1896.

The movement turned from social and literary pursuits to social justice and activism in the 1890s with the demise of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow, which killed any idea held by the black elite that their conduct and class would convince whites that blacks could be their equals. The 1890s was also the era of lynchings, and the decade was characterized by the watershed of blood staining the soil of the South (not only black Southerners, but Jewish Southerners, Italians, etc). Out of this violence came Ida B. Wells, a journalist who gained fame in the mid-1880s when she refused to give up her train seat to a white man and move to a Jim Crow car. Wells was dragged from the train, but she immediately hired a lawyer to sue the railroad company. She won her case in 1884, and received a settlement of $500. Though the railroad appealed the case, Wells earned a reputation as a powerful voice against racism and oppression. By the 1890s, Wells anti-lynching crusade was taken up by the various women’s clubs across the nation, and that issue, along with women’s suffrage, became the platforms upon which the National Association of Colored Women was founded in 1896.

The NAWC was the result of a merger of the National Federation of Afro-American Women, the Women’s Era Club of Boston, and the National League of Colored Women of Washington, DC, as well as smaller organizations that had arisen from the African-American women’s club movement. High profile founders included Harriet Tubman, Margaret Murray Washington, Frances E.W. Harper, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell. But its two leading members were Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Mary Church Terrell, whose original intention was “to furnish evidence of the moral, mental and material progress made by people of color through the efforts of our women.”

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was born in Boston of a Franco-African father from Martinique and a Cornish mother. She made waves early on in life first by her marriage to George Lewis Ruffin, the first black Harvard graduate and the first African American to serve on the Boston City Council, the Massachusetts state legislature, and as Boston’s first black municipal judge, and secondly by her association with Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone to form the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1869.

Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin was born in Boston of a Franco-African father from Martinique and a Cornish mother. She made waves early on in life first by her marriage to George Lewis Ruffin, the first black Harvard graduate and the first African American to serve on the Boston City Council, the Massachusetts state legislature, and as Boston’s first black municipal judge, and secondly by her association with Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone to form the American Woman Suffrage Association in 1869.

After her husband’s early death in 1884, Ruffin founded Woman’s Era, the first newspaper written by and for black American women, and called for her audience to agitate for the rights of their race and their sex. Even as she formed the National Federation of Afro-American Women and became a part of the NAWC, Ruffin remained a member of white women’s clubs, a matter which revealed the unyielding split between race and gender when the General Federation of Woman’s Clubs met in Milwaukee in 1900 and Ruffin was permitted to represent the white women’s clubs she belonged to, but not the black woman’s club, New Era. Nonetheless, Ruffin remained a force in the women’s club movement and became a charter member of the NAACP when it was formed in 1910.

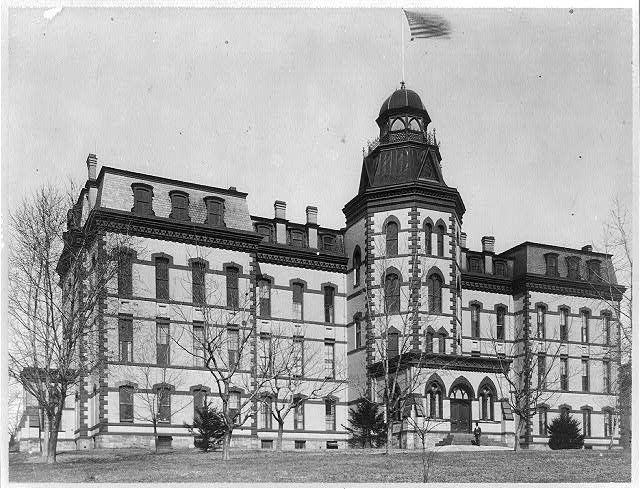

Mary Church Terrell came from a life of extreme privilege, being the daughter of Robert Church, the wealthiest black man in Memphis, Tennessee, where he owned extensive real estate. When she graduated from Oberlin College in 1884 with a bachelor’s degree, she was one of the first African-American women known to have earned a college degree, and she went on to earn a master’s degree from Oberlin in 1888. After college, Terrell traveled to Europe for more education, and became fluent in French, German, and Italian, a skill which served her well when she achieved international stature.

Mary Church Terrell came from a life of extreme privilege, being the daughter of Robert Church, the wealthiest black man in Memphis, Tennessee, where he owned extensive real estate. When she graduated from Oberlin College in 1884 with a bachelor’s degree, she was one of the first African-American women known to have earned a college degree, and she went on to earn a master’s degree from Oberlin in 1888. After college, Terrell traveled to Europe for more education, and became fluent in French, German, and Italian, a skill which served her well when she achieved international stature.

She married Robert H. Terrell, a lawyer who became the first black municipal court judge in Washington, DC, where she also became the first black woman in the United States to be appointed to the District of Columbia Board of Education. As with most educated black women, Terrell took to the pen, and though she was loathe to call herself a journalist, under the name Euphemia Kirk,” her articles appeared in both white and black newspapers where she “communicated a consistent message that effectively and decisively aligned with that of the African American Women’s Club Movement and the overall struggle of black women and the black race for equality.”

Other influential leaders included Fannie Barrier Williams, a Pennsylvania native who moved to Chicago in the 1890s who became involved in the establishment of Provident Hospital, an inter-racial medical facility that included a nursing training school that admitted black women, Frederick Douglass Center, a settlement house, and the Phillis Wheatley Home for Girls, among other notable achievements. When Barrier Williams was nominated to the prestigious Chicago Women’s Club in 1894, she and her supporters received threats, both public and private. Barrier Williams continued to fight for inclusion and was admitted in 1895. She was also the first black and the first woman on the Chicago Library Board.

Other influential leaders included Fannie Barrier Williams, a Pennsylvania native who moved to Chicago in the 1890s who became involved in the establishment of Provident Hospital, an inter-racial medical facility that included a nursing training school that admitted black women, Frederick Douglass Center, a settlement house, and the Phillis Wheatley Home for Girls, among other notable achievements. When Barrier Williams was nominated to the prestigious Chicago Women’s Club in 1894, she and her supporters received threats, both public and private. Barrier Williams continued to fight for inclusion and was admitted in 1895. She was also the first black and the first woman on the Chicago Library Board.

Her most lasting influence was during the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, where she fought for the inclusion of black achievements and was appointed as Clerk in charge of Colored Interests in the Department of Publicity and Promotions. Barrier then gave two speeches, “The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Women of the United States Since the Emancipation Proclamation,” which disputed the notion that slavery had rendered African-American women incapable of the same moral and intellectual levels as other women, and “What Can Religion Further Do to Advance the condition of the American Negro?”, which called upon churches, particularly those in the South, to open their doors to all people, regardless of race.

Though the women’s club movement was criticized by the black community as being elitist, these women saw themselves as forming a model for correct behavior, and as taking advantage of their social status and wealth to fight for the rights of their race and their sex. The motto, “Lifting as We Climb,” characterized their goals and achievements, which, as African-Americans and as women in the 19th and early 20th centuries, were outstanding.

Further Reading:

Aristocrats of Color: the Black Elite, 1880-1920 by Willard B. Gatewood

To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells by Mia Bay

A Colored Woman in a White World by Mary Church Terrell

African American women in the struggle for the vote, 1850-1920 by Rosalyn Terborg-Penn

Lifting As They Climb by Elizabeth Lindsay Davis

African American women and the vote, 1837-1965 by Ann Dexter Gordon & Bettye Collier-Thomas

Comments are closed.