The Country House and its society was taken very seriously by the British. Unlike their Continental counterparts, whose society adhered closely to the movements of the court, the British long acknowledged the countryside as the backbone of the country. The Englishman actually preferred to live in the country, finding on his land a range of sporting activities and like-minded tenants and neighbors; his home was his country seat no matter how much time he spent in London or abroad. According to T.H.S. Escott, the country house as a social entity first appeared during the time of Chaucer, and cemented its purpose as a center of social and political life by the time of the Tudors. Though by the Edwardian era, the country and the country house had begun to lose a bit of its importance, anyone and everyone within “society” knew the quickest way to establish roots and display one’s wealth was to buy a country estate and a few acres, and regularly host house parties.

The years between 1861 and 1914 were considered the “golden age” of country house entertaining. Yes, country house parties existed prior to this time, as seen in Lord Byron’s poem “A Country House Party,” where he indeed described “[t]he politicians, in a nook apart, Discuss’d the world, and settled all the spheres;” but never before was it undertaken in such militaristic order, was it considered a vital part of the year-long social season, and more important–was extremely expensive. It was this great expense–much of it spent entertaining the easily-bored Prince of Wales–that opened the door for the entry of wealthy Jewish families into British (and later on, French, and to a much lesser degree, German) society.

The years between 1861 and 1914 were considered the “golden age” of country house entertaining. Yes, country house parties existed prior to this time, as seen in Lord Byron’s poem “A Country House Party,” where he indeed described “[t]he politicians, in a nook apart, Discuss’d the world, and settled all the spheres;” but never before was it undertaken in such militaristic order, was it considered a vital part of the year-long social season, and more important–was extremely expensive. It was this great expense–much of it spent entertaining the easily-bored Prince of Wales–that opened the door for the entry of wealthy Jewish families into British (and later on, French, and to a much lesser degree, German) society.

This lavish expenditure had its casualties, and many of Bertie’s closest friends found themselves bankrupt: Sir Christopher Sykes (his sister-in-law had to buttonhole Bertie to get him to pay Sir Christopher’s debts), Harry Chaplin (who had to sell his estates and his possessions), and Daisy, Countess of Warwick (who threatened George V with the publication of Bertie’s love letters to her in order to keep bankruptcy at bay). But while the fun lasted, boy did they have it! Sometimes lasting a week, but usually held from Saturday to Monday (hence the name “Saturday-to-Monday” as the phrase “week-end” was considered a vulgar Americanism), each day was packed with activities.

Though parties were held during the Season at the few recesses in Parliament, August and September were the months for country house parties, as that was the height of the shooting. The former month was generally reserved for the visits of relatives, and many houses focused around cricket. Most people visited the same houses year after year, and if there was an awkward gap between the ending of one house party and the beginning of another, a relative or intimate of the hostess was permitted to remain until departure–the unknown, however, was advised to leave and remain in town until it was time to depart. The latter month was the time for shooting parties, and the first week of September, harvest permitting, was when the crack guns appeared. Etiquette required different form for small shooting parties, large shooting parties, parties to which royalty was invited, and shooting parties held for intimates or relations, but all types lasted three days. Many etiquette books of the time stressed that the success of the house party mainly depended upon people knowing one another–this was important for the men out in the field with the guns, and of particular importance to the ladies, who were expected to amuse themselves while the men went out shooting.

Though parties were held during the Season at the few recesses in Parliament, August and September were the months for country house parties, as that was the height of the shooting. The former month was generally reserved for the visits of relatives, and many houses focused around cricket. Most people visited the same houses year after year, and if there was an awkward gap between the ending of one house party and the beginning of another, a relative or intimate of the hostess was permitted to remain until departure–the unknown, however, was advised to leave and remain in town until it was time to depart. The latter month was the time for shooting parties, and the first week of September, harvest permitting, was when the crack guns appeared. Etiquette required different form for small shooting parties, large shooting parties, parties to which royalty was invited, and shooting parties held for intimates or relations, but all types lasted three days. Many etiquette books of the time stressed that the success of the house party mainly depended upon people knowing one another–this was important for the men out in the field with the guns, and of particular importance to the ladies, who were expected to amuse themselves while the men went out shooting.

As you can tell, shooting was considered very important to Edwardian men. Landowners vied with one another to produce the biggest “bags” each year, and the numbers increased by leaps and bounds. At the home of the Earl of Pembroke, three days produced 1,236 head, 1,142 head, and 2,276 head, respectively, and this was thought normal. This competitive streak led to the most infamous shoot in 1913 at Hall Barn, a Buckinghamshire estate owned by Lord Burnham, of 3,937 pheasants–which led to even King George V remarking “perhaps we overdid it today.” Against the boom of guns, ladies usually scribbled letters, a practice of much amusement to foreigners who could not imagine how busy an Englishwoman’s life was, creating the need for correspondence on political, social and household topics.

As you can tell, shooting was considered very important to Edwardian men. Landowners vied with one another to produce the biggest “bags” each year, and the numbers increased by leaps and bounds. At the home of the Earl of Pembroke, three days produced 1,236 head, 1,142 head, and 2,276 head, respectively, and this was thought normal. This competitive streak led to the most infamous shoot in 1913 at Hall Barn, a Buckinghamshire estate owned by Lord Burnham, of 3,937 pheasants–which led to even King George V remarking “perhaps we overdid it today.” Against the boom of guns, ladies usually scribbled letters, a practice of much amusement to foreigners who could not imagine how busy an Englishwoman’s life was, creating the need for correspondence on political, social and household topics.

Besides sport, food was one of the more important aspects of a country house party. Guests were free to arrive at breakfast when they so chose, but the proper hour was usually between nine and half past ten. Far from the simple repast enjoyed at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Edwardian guests would feast on fruits, eggs, potted meats, fish, toast, rolls, tea cakes, muffins, hams, tongues, pies, kidney, fried bacon and were given tea, coffee, hot cocoa, and juices to drink. The sportsman’s breakfast was even more substantial, including game pie, cold beef, deviled turkey, broiled ham, kippered haddock, collared eels, spiced beef, shrimp, cold fowl, curried eggs, toasted mushrooms and broiled mackerel among other things, and though tea and coffee were taken, a tankard of beer or a cherry brandy were the drink of choice. Luncheon was included at some houses, though many remained old-fashioned and stuck to the meal times of breakfast, dinner and supper. Luncheons were both formal–with everyone seated by rank–and informal–the gentlemen served the ladies and sometimes children were invited down. The dishes served were a little fancier though similar to breakfast, and beverages included claret, sherry and a light beer. Dinners were more formal, and suppers were the typical sumptuous, formal affairs. Afternoon tea was a given, of course.

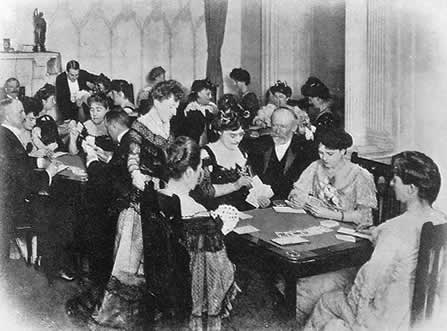

Indoor amusements such as word games, charades and practical jokes were the norm, but a passion for gambling overtook the fast set during the 1880s. Baccarat was the initial game of choice and no hostess threw a country house party without a baccarat game. The Prince of Wales was a particular fan of this illegal card game, and until the scandal at Tranby Croft, he carried his own set of counters on his person at all times in case of an impromptu hand. Because of the publicity, baccarat was discontinued in society, and just as quickly as that went out, bridge came in. The craze swept women in particular, and during the early 1900s, the conversation of the most obsessed centered around bridge, bridge, bridge! Ladies were known to play hands in between eating, before going to bed, and would neglect dancing in favor of sitting down for a game in a drawing room. The founding of ladies’ clubs in the mold of gentlemen’s clubs fostered this obsession, for now women would give the same excuse as their husbands as to why they were late to supper or had to hurry into their evening dress.

Indoor amusements such as word games, charades and practical jokes were the norm, but a passion for gambling overtook the fast set during the 1880s. Baccarat was the initial game of choice and no hostess threw a country house party without a baccarat game. The Prince of Wales was a particular fan of this illegal card game, and until the scandal at Tranby Croft, he carried his own set of counters on his person at all times in case of an impromptu hand. Because of the publicity, baccarat was discontinued in society, and just as quickly as that went out, bridge came in. The craze swept women in particular, and during the early 1900s, the conversation of the most obsessed centered around bridge, bridge, bridge! Ladies were known to play hands in between eating, before going to bed, and would neglect dancing in favor of sitting down for a game in a drawing room. The founding of ladies’ clubs in the mold of gentlemen’s clubs fostered this obsession, for now women would give the same excuse as their husbands as to why they were late to supper or had to hurry into their evening dress.

However, the most engrossing activity of the country house party was sex. Love affairs were the tune of the day, and once a gentleman and a lady had made it known to their hostess that they wished to consummate their attraction to one another, the hostess knew she’d better arrange room assignments to facilitate this. An Edwardian love affair was not an instantaneous matter. The couple in question might spend a few months, or even a few years expressing their affection to one another through letters, and with the amount of clothing involved and the presence of observant servants, getting into bed with one another was not an easy deal–even at a neatly arranged country house party. Anita Leslie tells the story of Lord Charles Beresford who, groping in the dark for his lady love’s bedroom, pushed open the door and leaped into the bed with a “cock-a-doodle-doo!” only to discover he’d slipped between a Archbishop and his wife. Another embarrassing story is that of a hungry guest who wandered through the halls in search of a bite to eat and found a plate of sandwiches on the floor in front of a bedroom door. He satisfied his hunger, ignorant of the intentions meant by the plate and the gentleman hoping for a “yes” from the lady was left disappointed by the tray’s barren surface.

However, the most engrossing activity of the country house party was sex. Love affairs were the tune of the day, and once a gentleman and a lady had made it known to their hostess that they wished to consummate their attraction to one another, the hostess knew she’d better arrange room assignments to facilitate this. An Edwardian love affair was not an instantaneous matter. The couple in question might spend a few months, or even a few years expressing their affection to one another through letters, and with the amount of clothing involved and the presence of observant servants, getting into bed with one another was not an easy deal–even at a neatly arranged country house party. Anita Leslie tells the story of Lord Charles Beresford who, groping in the dark for his lady love’s bedroom, pushed open the door and leaped into the bed with a “cock-a-doodle-doo!” only to discover he’d slipped between a Archbishop and his wife. Another embarrassing story is that of a hungry guest who wandered through the halls in search of a bite to eat and found a plate of sandwiches on the floor in front of a bedroom door. He satisfied his hunger, ignorant of the intentions meant by the plate and the gentleman hoping for a “yes” from the lady was left disappointed by the tray’s barren surface.

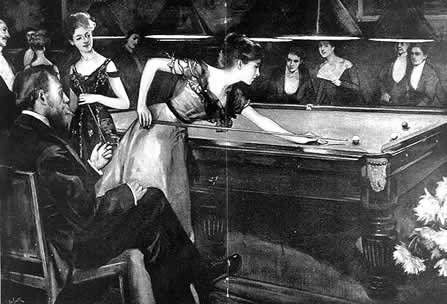

More innocently (or perhaps not), the house party was the last hurrah of that season’s marriage mart. Mama’s who hadn’t caught a suitable gentleman for their daughter that season could count on a house party and its sympathetic hostess to bring the girl in contact with the man of her or her parent’s choice. Activities such as picnics, walks, riding, croquet, billiards and lawn tennis could show off the young lady at her best angle and prove to the gentleman her intelligence and worthiness of being his bride. Other important uses for the country party was its original purpose: politics. The Souls centered around Taplow Court, the home of the Desboroughs, and Stanway House (the Earls of Wemyss), and Nancy Astor’s home at Cliveden formed the setting for a band of Boer War veterans and Pro-Rhodesian Imperialists known as Milner’s Kindergarten. Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905, was a prodigious golfer, and his intense interest in this Scottish sport led to its adoption by hostesses as part of the country house program.

More innocently (or perhaps not), the house party was the last hurrah of that season’s marriage mart. Mama’s who hadn’t caught a suitable gentleman for their daughter that season could count on a house party and its sympathetic hostess to bring the girl in contact with the man of her or her parent’s choice. Activities such as picnics, walks, riding, croquet, billiards and lawn tennis could show off the young lady at her best angle and prove to the gentleman her intelligence and worthiness of being his bride. Other important uses for the country party was its original purpose: politics. The Souls centered around Taplow Court, the home of the Desboroughs, and Stanway House (the Earls of Wemyss), and Nancy Astor’s home at Cliveden formed the setting for a band of Boer War veterans and Pro-Rhodesian Imperialists known as Milner’s Kindergarten. Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister from 1902 to 1905, was a prodigious golfer, and his intense interest in this Scottish sport led to its adoption by hostesses as part of the country house program.

So important was the country house that even royalty took part. After extensive renovation, the Prince of Wales and his family hosted many an important party at Sandringham in Norfolk. Here, the clocks were set forward half an hour–not to accommodate the Princess of Wales’s habitual tardiness as many memoirs claim, but to allow more time for hunting. Because of this, that half-hour ahead was known as “Sandringham Time.” The motor car made it easier to get to country house parties, and newspaper reports of the 1910s bemoaned the emptiness of London due to the dash of society to the country every Friday evening in their motors. Though the Great War further decimated the political importance of the country house, it remained and has remained a symbol that “All’s right with the world!”

Further Reading:

The Country House Party by Phyllida Barstow

The Marlborough House Set by Anita Leslie

Society in the Country House by Thomas Hay Sweet Escott

Manners and Rules of Good Society by A Member of the Aristocracy

Etiquette of Good Society by Lady Colin Campbell

“A Country House Party” by Lord Byron in A Satire Anthology by Carolyn Wells

I loved your blog. It immersed me in the setting and the times.

So glad you included information about the food served at these parties. It’s an often neglected part of romances these days I think. I blogged about that topic today at seducedbyhistory.blogspot.com/

I love food–am a total foodie, and I bemoan the lack of food in romance as well. Sherry Thomas’s Delicious is the only historical romance in my recent reading that has described food in intimate detail, and I know that Jane Feather’s Edwardian trilogy found food important. But I chalk the absence up to the further wallpapering of history. :/

Great post. While this is not my era, it seems, as always, the more things change, the more they remain the same.

Can’t say I’d enjoy “collared eels” or any number of the dishes mentioned, but the fact that people would pauper themselves for their entertainments must, of course, include the food. I have no doubt hostesses of the time, like hostesses of today, would turn the pantry inside out to have the most lavish table–as they have since the dawn of time. .

Thanks for the interesting read.

I don’t know Pat, the collared eels sound delightful–except for the eel part. 😀

Thanks for stopping by!

Great post. This is a topic I am fascinated with. And you hit the nail right on the head noting that sport and sporting food were the two most important aspects of a country house party.

*

But I have seen lots of images of shooting parties where the women looked too cold, not at ease and as if they would have rather been comfortably inside the house. I wonder if they were just supporting their husbands, or if women really loved to shoot. (Not riding.. that was something different).

*

Thanks for the link

Hels

I have as well! Since ladies didn’t really shoot (and if they were so inclined, it still wouldn’t happen on as large a scale as the men, since shooting was considered a masculine sport), I’ll second your assumption that they were only out there for support.