It was no coincidence that with the rise in female education, female employment would also rise in prominence. Something monumental happened to English society with the passing of the Education Act of 1870, wherein schooling was provided to all children between the ages of five and twelve, with elementary school made compulsory in 1880, and free in 1891. Add to this the founding of women’s colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, the granting of degrees to women from other colleges and universities (something Oxbridge did not do until the 20th century), as well as the fight for secondary education and the founding of girls’ public schools and high schools, and you have a veritable revolution in thought! As a result of these monumental changes, women and teenage girls of the Edwardian era were the first generation of females to be educated along the same standards as males.

It was no coincidence that with the rise in female education, female employment would also rise in prominence. Something monumental happened to English society with the passing of the Education Act of 1870, wherein schooling was provided to all children between the ages of five and twelve, with elementary school made compulsory in 1880, and free in 1891. Add to this the founding of women’s colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, the granting of degrees to women from other colleges and universities (something Oxbridge did not do until the 20th century), as well as the fight for secondary education and the founding of girls’ public schools and high schools, and you have a veritable revolution in thought! As a result of these monumental changes, women and teenage girls of the Edwardian era were the first generation of females to be educated along the same standards as males.

And this came at the perfect time for late Victorian and Edwardian women. By the 1860s and 1870s, the “Surplus Woman Question” was the subject of countless articles, lectures, and pamphlets. Despite the age-old opinion that women were meant for marriage and motherhood, the uncomfortable reality that hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of women would not wed because of poverty, age, physical appearance, lack of position, and especially a shortage of eligible men, frightened society. However, no one offered any real solutions besides devoting one’s self to one’s aging parents, or becoming a caretaker/governess for the household of one’s married brother or sister. Women of the 1880s revolted against this dreary existence and slowly, but surely, began to infiltrate the workforce as shop-girls, teachers, librarians, journalists, nurses, etc. Of course, though there was a bit of a struggle against women “de-feminizing” themselves by having a job, the rapid modernization of technology and business made their entry much easier than in the past (for example, the growth of ocean liners meant stewardesses were needed for female passengers; the growth of department stores over individual shops meant female employees were needed in certain departments, etc).

One profession which reigned king (or queen) above all was the type-writer girl, or typist. As one of the better paying and most “genteel” of positions, it was highly coveted by professional women. A woman possessing skills in typing, dictation, and shorthand could work as a private secretary, an authors’ amanuensis, a copying clerk to a solicitor, or for the Government. To equip women with the necessary skills, business schools and classes were founded, and after a stated period of time, the student was awarded a certificate, which verified to prospective employers that the applicant was trained and experienced in the aforementioned skills, as well as light book-keeping, business terms, business arithmetic, and précis (the summarizing of “a document in the fewest possible words, consistently with clearness and accuracy”).

One profession which reigned king (or queen) above all was the type-writer girl, or typist. As one of the better paying and most “genteel” of positions, it was highly coveted by professional women. A woman possessing skills in typing, dictation, and shorthand could work as a private secretary, an authors’ amanuensis, a copying clerk to a solicitor, or for the Government. To equip women with the necessary skills, business schools and classes were founded, and after a stated period of time, the student was awarded a certificate, which verified to prospective employers that the applicant was trained and experienced in the aforementioned skills, as well as light book-keeping, business terms, business arithmetic, and précis (the summarizing of “a document in the fewest possible words, consistently with clearness and accuracy”).

In London, the Metropolitan School for Shorthand, in Chancery Lane, charged five guineas for a complete course of instruction until a rate of about 120 words a minute was reached by the student (a half-a-guinea could be paid weekly, with the fee reduced to 5s. if evening classes were attended). A prospective typist could also learn to use the typewriter at the chief or branch offices of the leading typewriter makers, and frequently these classes were free with purchase. The pay for a typist or secretary varied based on experience and position. A shorthand and typewriting clerk could have been paid anything from a beginner’s 15s. to £2 or £3 a week, whilst a secretary was paid from the assistant’s £50 to £250 a year. Oddly enough, though positions as copying for a solicitor or typing manuscripts were difficult to obtain, the pay was quite poor–about £5 for a novel of 100,000 words.

The most dependable and lucrative positions were found working for the Civil Service. Of the departments opened to women typists, they included the Board of Education (England), Colonial Office, Customs, Foreign Office, India Office, Inland Revenue, Office of the Secretary for Scotland, Treasury, and War Office (including Royal Army Clothing Depot). To become a typist in a Government department, a woman was required to be between the ages of 18 and 30, be unmarried or widowed, “duly qualified in respect of health and character,” a natural born or naturalized British subject, and at least five feet in height without boots or shoes. The examination for employment included “writing, spelling, English composition, copying manuscript, arithmetic (first four rules, simple and compound, including English weights and measures, and reduction), typewriting; and, if required by the department by which the candidate has been nominated, shorthand–and they were required to pass all topics.

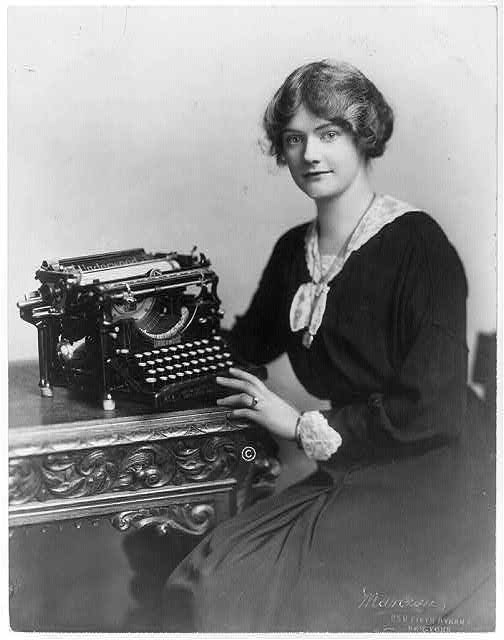

Though domestic service continued to dominate womens’ employment, the professional class of women were solid and formidable. For the first time, possible ever in history, women could and did find work outside of the home through which they could support themselves. Granted, the issue of imbalanced pay between male and female employees exists ’til this day, but in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, “surplus women” were no longer pathetic, mild-mannered creatures to be pitied: they were independent and resilient women who forged an individual path in spite of society’s dictates. And for women like Gwen (left), the typewriter was an instrument of dramatic social change.

Though domestic service continued to dominate womens’ employment, the professional class of women were solid and formidable. For the first time, possible ever in history, women could and did find work outside of the home through which they could support themselves. Granted, the issue of imbalanced pay between male and female employees exists ’til this day, but in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, “surplus women” were no longer pathetic, mild-mannered creatures to be pitied: they were independent and resilient women who forged an individual path in spite of society’s dictates. And for women like Gwen (left), the typewriter was an instrument of dramatic social change.

Further Reading:

Bluestockings: The Remarkable Story of the First Women to Fight for an Education by Jane Robinson

Girls Growing Up in Late Victorian and Edwardian England by Carol Dyhouse

The Englishwoman’s Year Book (1900 edition) ed. by Emily Janes

Every Woman’s Encyclopaedia v1 (1912)

The Type-writer Girl by Grant Allen (writing as Olive Pratt Rayner)

Interesting Articles:

The Cultural Work of the Type-writer Girl by Christopher Keep

Surplus Negro Women (1908) by Kelly Miller

Blogs of Note:

Fresh Ribbon

Life in a Typewriter Shop

Our ancestor George Jezard was a P&O steward in his daughter Violet Jezard’s 1896 baptism (born 1890). It is quite possible that his wife May Jezard was a P&O stewardess. Their daughter Violet stayed at a boarding school in Southend, no doubt so that her parents could go straight to her when they returned from a sea voyage. As we are unable to trace any official records relating to George Jezard and May Jezard it is quite possible that they married abroad and were abroad when the 1911, 1901 and 1891 censuses were taken or chose to live abroad after seeing other countries.