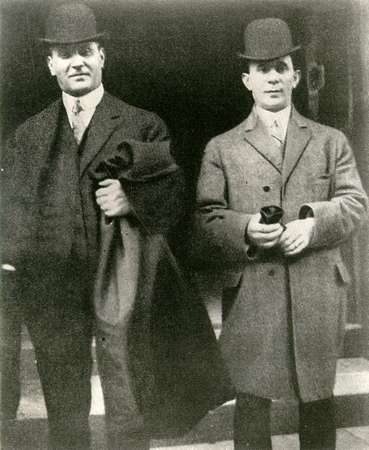

March 25, 2009 is the 98th anniversary of the fire that tore through the workrooms of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and left 148 women dead. It had been a normal day in the factory where hundreds of young immigrant women worked in fourteen hour shifts for six or seven dollars a week to make shirtwaists for the Triangle Shirtwaist Company, owned by Max Blanck and Isaac Harris. The company in which these young women labored was located on the top three floors of the ten-floor Asch Building at Greene Street and Washington Place, just east of Washington Square. Hard-worked they were, but these young women had won a notable victory just two years before, putting the shirtwaist factory in the public eye when they struck boldly for higher wages and better working conditions in event known as the “Uprising of 20,000.”

That day the young women stretched their arms and cramped fingers, joking and chatting with one another as they tidied their workstations and shoved their arms into their coats as the clock’s hands pulled closer to 4:45. Then someone yelled “Fire!” Within moments panic broke out amongst the workers and everyone scattered, jamming doorways and halls in an effort to escape. Outside, United Press reporter William G. Shepard happened to stroll near the area when he suddenly saw smoke:

I reached the building before the alarm was turned in. I saw every feature of the tragedy visible from outside the building. I learned a new sound–a more horrible sound than description can picture. It was the thud of a speeding, living body on a stone sidewalk.

Thud—dead, thud—dead, thud—dead, thud—dead. Sixty-two thud—deads. I call them that, because the sound and the thought of death came to me each time, at the same instant. There was plenty of chance to watch them as they came down. The height was eighty feet.

The first ten thud—deads shocked me. I looked up—saw that there were scores of girls at the windows. The flames from the floor below were beating in their faces. Somehow I knew that they, too, must come down, and something within me—something that I didn’t know was there—steeled me.

I even watched one girl falling. Waving her arms, trying to keep her body upright until the very instant she struck the sidewalk, she was trying to balance herself. Then came the thud–then a silent, unmoving pile of clothing and twisted, broken limbs.

To his horror, and that of the crowd rushing to the scene of the fire, more young women jumped from the burning building. Firemen appeared on the scene, but the ladders were too short, and the life nets held aloft for the jumping girls to land on tore upon impact. All around the building lay dead bodies, broken, charred and covered with blood. The fire was put out not an hour later, and firemen rushed to the top three floors and were met with dozens of burnt bodies. They cleared the building of the last body by 11 that night.

The following day, grieving relatives and curious onlookers streamed through the morgue set up on the 26th Street pier to identify the dead. By April, the public outcry against the unsafe working conditions in New York forces the authorities to do something about this long-neglected blight on the city. That same month, owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck are indicted for manslaughter in connection with the fire deaths. Further reports indicated that the escape route from the ninth floor was blocked by a locked door. Harris and Blanck were brought to trial in December and to the horror of the crowd, they were found “not guilty” after a deliberation of two hours.

The following day, grieving relatives and curious onlookers streamed through the morgue set up on the 26th Street pier to identify the dead. By April, the public outcry against the unsafe working conditions in New York forces the authorities to do something about this long-neglected blight on the city. That same month, owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck are indicted for manslaughter in connection with the fire deaths. Further reports indicated that the escape route from the ninth floor was blocked by a locked door. Harris and Blanck were brought to trial in December and to the horror of the crowd, they were found “not guilty” after a deliberation of two hours.  The family of the victims and the survivors took Harris and Blanck to court in a civil suit and in 1914, the twenty-three individual suits for damages against Triangle were settled for an average of just $75 per life lost. In the aftermath of the fire, New York created a Factory Investigating Commission to examine the need for new legislation to prevent future fire disasters. In part because of the work of the Commission, “the golden era in remedial factory legislation” was launched and over the next three years, New York enacted 36 new safety laws.

The family of the victims and the survivors took Harris and Blanck to court in a civil suit and in 1914, the twenty-three individual suits for damages against Triangle were settled for an average of just $75 per life lost. In the aftermath of the fire, New York created a Factory Investigating Commission to examine the need for new legislation to prevent future fire disasters. In part because of the work of the Commission, “the golden era in remedial factory legislation” was launched and over the next three years, New York enacted 36 new safety laws.

Today we are linked to the tragedy through Rose Freedman, last living survivor of the fire, who died in 2001 age 107 and the designation of The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building (Brown Building) as a National Historical Landmark. For more information, please visit the following websites:

The Triangle Shirtwaist Fire Trial

The Triangle Factory Fire

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Building

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire Memorial

The fire in fiction:

The Locket: Surviving the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire by Suzanne Lieurance

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory by Charity Barger

Triangle: A Novel by Katharine Weber

Ashes of Roses by Mary Jane Auch