With love and marriage, there can unfortunately be divorce. For our Edwardian counterparts, divorce was a difficult and arduous process that could be, depending upon the social circle, a one-way ticket to the cut direct.

The law of England regarded marriage as a contract, a status and institution. Up until 1857, divorce was administered by ecclesiastical courts, who created  such a long, frustrating and expensive route to end a marriage, most unhappy couples had no choice but to remain together. Upon the passing of the controversial Divorce Act of 1857, the jurisdiction was passed from the ecclesiastical courts to a new civil tribunal, and absolute divorce was sanctioned with permission of remarriage on proof of adultery on the part of the wife, or adultery and cruelty on the part of the husband.

such a long, frustrating and expensive route to end a marriage, most unhappy couples had no choice but to remain together. Upon the passing of the controversial Divorce Act of 1857, the jurisdiction was passed from the ecclesiastical courts to a new civil tribunal, and absolute divorce was sanctioned with permission of remarriage on proof of adultery on the part of the wife, or adultery and cruelty on the part of the husband.

For the miserable couple willing to weather the scandal and the exclusion from the choicest circles, if not the still considerable expense, the application for divorce would be made by a petition to the Probate Divorce and Division of the Court of Justice. The party seeking relief was called the “petitioner” and the party against whom the petition is brought was called the “respondent“. If the wife was accused of adultery, the party with whom she committed this “criminal act” was the “co-respondent.” However, the person with whom the wife alleged her husband had committed adultery was not a party to the suit–but a woman implicated in a divorce suit could, upon proper application, be allowed to secure an order permitting her to attend the proceedings as an “intervener.”

While a husband was entitled to a divorce if his wife committed adultery, a wife had to jump through hoops. Besides adultery, a husband had to commit incestuous adultery, bigamy, rape, sodomy, bestiality, adultery coupled with cruelty, or adultery coupled with desertion without reasonable excuse for two years or more. Incestuous adultery was adultery with a woman within the prohibited degrees (sister, grandmother, mother-in-law, etc). Furthermore, a wife would not be granted a degree of divorce on the grounds of cruelty and adultery, unless the cruelty consisted of bodily hurt or injury to health, and at least two acts of cruelty on the party of the husband were required. Thankfully (in this instance at least), the communication of venereal disease when the husband knew of his condition was considered an act of cruelty.

While a husband was entitled to a divorce if his wife committed adultery, a wife had to jump through hoops. Besides adultery, a husband had to commit incestuous adultery, bigamy, rape, sodomy, bestiality, adultery coupled with cruelty, or adultery coupled with desertion without reasonable excuse for two years or more. Incestuous adultery was adultery with a woman within the prohibited degrees (sister, grandmother, mother-in-law, etc). Furthermore, a wife would not be granted a degree of divorce on the grounds of cruelty and adultery, unless the cruelty consisted of bodily hurt or injury to health, and at least two acts of cruelty on the party of the husband were required. Thankfully (in this instance at least), the communication of venereal disease when the husband knew of his condition was considered an act of cruelty.

Barring condonation (where a matrimonial offense, which is a sufficient cause for divorce, is condoned or forgiven by the spouse aggrieved), connivance (where the adultery complained of was committed by the connivance or active consent of the petitioner) or collusion (the illegal agreement and co-operation between the petitioner and the respondent in a divorce action to obtain a judicial dissolution of the marriage), the couple was on its way to receiving a decree nisi. If, after six months, it was unaffected by any intervention by the King’s Proctor or any other person it could be made decree absolute upon proper application.

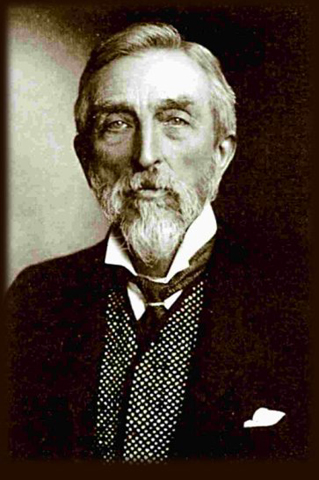

For the gentleman or lady who desired lose an undesirable spouse, there was no greater a solicitor than Sir George Lewis of Ely Place, Holburn. Described by contemporary portraits as a “pleasant-voiced, white-haired, dapper little man” who was the “depository of so many scandalous secrets,” it was he who helped society’s brightest extricate themselves from sticky situations–such as the time when Lady Charles Beresford attempted to blackmail the Countess of Warwick into breaking off her relations with Lord Charles, and Lady Warwick brought in the Prince of Wales to back her up.

For the gentleman or lady who desired lose an undesirable spouse, there was no greater a solicitor than Sir George Lewis of Ely Place, Holburn. Described by contemporary portraits as a “pleasant-voiced, white-haired, dapper little man” who was the “depository of so many scandalous secrets,” it was he who helped society’s brightest extricate themselves from sticky situations–such as the time when Lady Charles Beresford attempted to blackmail the Countess of Warwick into breaking off her relations with Lord Charles, and Lady Warwick brought in the Prince of Wales to back her up.

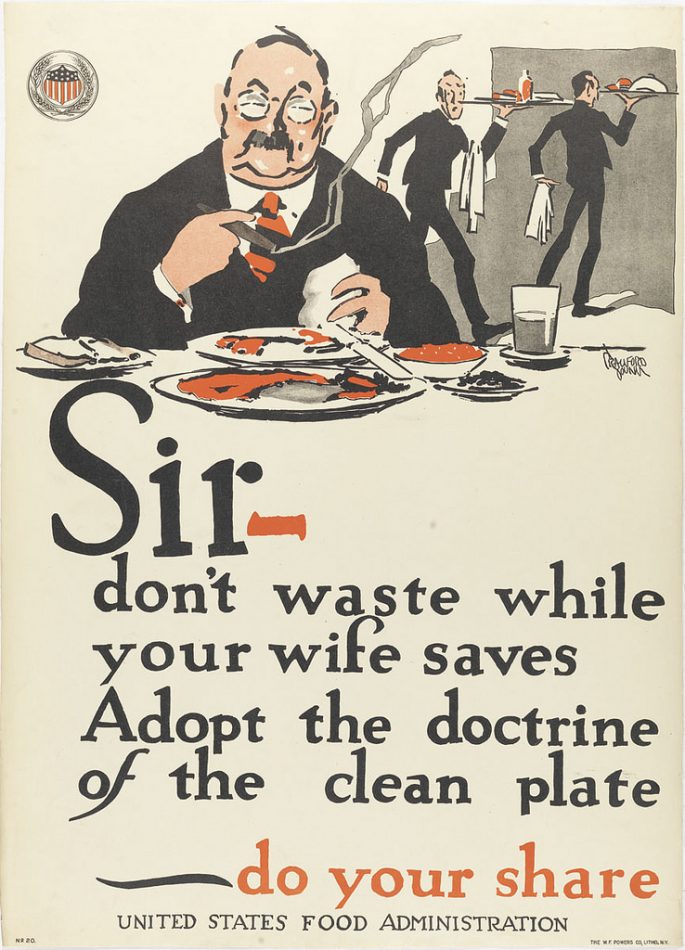

The divorce court itself was a source of entertainment. On almost any day, particularly if a scandalous case was being tried, a line some fifty or sixty people deep, made mostly of women, queued up at Royal Courts of Justice the for a seat in the public gallery. This was a considerable annoyance to junior barristers, who, especially when an aristocratic trial brought a crush, were perpetually unable to find a sufficient number of seats.

Despite collusion nullifying a petition for divorce, it was a standard procedure for couples who just couldn’t stand one another. To spare the wife even greater scandal, she would hire a private detective to follow her husband on an appointed night, the husband himself having hired a lady to impersonate his lover, and there would be proof of adultery. On the other hand, a wife could publicly refuse to share her husband’s bed, and he could sue for divorce based on her repudiation of his conjugal rights. If divorce was unobtainable, a couple could petition for a legal separation, which was easier to receive, but the prospect of a future divorce was made a bit more difficult.

The most difficult part of an English divorce were the children. Unlike in France or America, where children of divorced parents lost nothing and were at liberty to watch over their bringing-up, according to English law, a guilty mother was entirely deprived of their custody and even access (however, it was allowed for a faithless father). Under no circumstances, if the mother was found guilty, would she have custody of the children regardless of their ages. In divorce, the guilty woman lost everything: income, custody and access to children, reputation, and even in some cases her husband’s name.

where children of divorced parents lost nothing and were at liberty to watch over their bringing-up, according to English law, a guilty mother was entirely deprived of their custody and even access (however, it was allowed for a faithless father). Under no circumstances, if the mother was found guilty, would she have custody of the children regardless of their ages. In divorce, the guilty woman lost everything: income, custody and access to children, reputation, and even in some cases her husband’s name.

Sources:

Thirty-five Years in the Divorce Court by Henry Edwin Fenn

Inside the Victorian Home: A Portrait of Domestic Life in Victorian England by Judith Flanders

The Eighth Year by Phillip Gibbs

Edwardian Stories of Divorce by Janice Hubbard Harris

Marriage and Divorce Laws of the World by Hyacinthe Ringrose

This is good and interesting history, but it would be much better if you cited your sources, not necessarily footnote style, but some references at the end of the article. Then I could refer my history students to these posts.

Will do!

Wonderful post. I am reminded of the case of Lord Randolph Churchill whose brother was about to be implicated in a divorce trial, and how they tried to blackmail the Prince of Wales to stop it. Wasn’t POW also called as a witness once in another divorce case?

He almost was, I believe. Randolph threatened Bertie to pressure Joe into dropping the suit. He was called to the stand in the Lady Mordaunt divorce case–naughty Bertie, visiting a married woman alone and writing her (fairly innocuous) letters!

What a fascinating article, glad that equality has moved on a bit since then, and even more glad, as I’m a family law solicitor , that divorce has changed and the process is (slightly) less stressful.