After reading The New York Magazine’s list of the Top 20 Chef Empires, and perusing a few culinary books I’d borrowed from the library, I was struck, dumbstruck actually, that all save one of those twenty names are those of men. Many would argue that the age of modern cookery was of the turn of the century. Not only were chefs lifting food to its highest degree, but more and more people were able to partake of the sumptuous, delicate tastes a cook could create due to the falling food prices and rising incomes, if not the lucrative opportunities skilled French cooks could find in the kitchens of America and Europe’s new and fabulously rich. Right around the Edwardian era we saw an explosion of foodie treats, and most notably, women were involved–the “Queen of Cooks,” Rosa Lewis; Fannie Farmer, who raised the Boston Cooking School to prominence; and Marthe Distel, who founded culinary magazine La Cuisinière Cordon Bleu and offered subscribers cooking classes with professional chefs, which in turn led to the formation of Le Cordon Bleu cooking school.

After reading The New York Magazine’s list of the Top 20 Chef Empires, and perusing a few culinary books I’d borrowed from the library, I was struck, dumbstruck actually, that all save one of those twenty names are those of men. Many would argue that the age of modern cookery was of the turn of the century. Not only were chefs lifting food to its highest degree, but more and more people were able to partake of the sumptuous, delicate tastes a cook could create due to the falling food prices and rising incomes, if not the lucrative opportunities skilled French cooks could find in the kitchens of America and Europe’s new and fabulously rich. Right around the Edwardian era we saw an explosion of foodie treats, and most notably, women were involved–the “Queen of Cooks,” Rosa Lewis; Fannie Farmer, who raised the Boston Cooking School to prominence; and Marthe Distel, who founded culinary magazine La Cuisinière Cordon Bleu and offered subscribers cooking classes with professional chefs, which in turn led to the formation of Le Cordon Bleu cooking school.

Yet these women have been consigned to the footnotes of history. Farmer’s Boston Cooking School cookbook does remain in print, but as I’ve quickly noticed, Victorian/Edwardian cookbooks written by women are shunted into the domestic sphere, while those authored by men become authoritative. This strange dichotomy of the kitchen is fascinating. Cooking, in its basic format, is seen largely as a feminine position, yet once a man steps into the kitchen it becomes one of power. The male chef is master, he is king of the domain–in etiquette manuals, one never reads of tyrannical female cooks who must be handled with kid gloves. The careers of Rosa Lewis and Auguste Escoffier run parallel, yet Lewis is mentioned frequently in tandem with sex (she was rumored to be the mistress of Edward VII, and her hotel was allegedly a place where English aristocrats met with their mistresses), and Escoffier is lauded as the creator of modern French cookery, despite the fact that the success of his career is also due to the opening of a famous hotel.

Yet these women have been consigned to the footnotes of history. Farmer’s Boston Cooking School cookbook does remain in print, but as I’ve quickly noticed, Victorian/Edwardian cookbooks written by women are shunted into the domestic sphere, while those authored by men become authoritative. This strange dichotomy of the kitchen is fascinating. Cooking, in its basic format, is seen largely as a feminine position, yet once a man steps into the kitchen it becomes one of power. The male chef is master, he is king of the domain–in etiquette manuals, one never reads of tyrannical female cooks who must be handled with kid gloves. The careers of Rosa Lewis and Auguste Escoffier run parallel, yet Lewis is mentioned frequently in tandem with sex (she was rumored to be the mistress of Edward VII, and her hotel was allegedly a place where English aristocrats met with their mistresses), and Escoffier is lauded as the creator of modern French cookery, despite the fact that the success of his career is also due to the opening of a famous hotel.

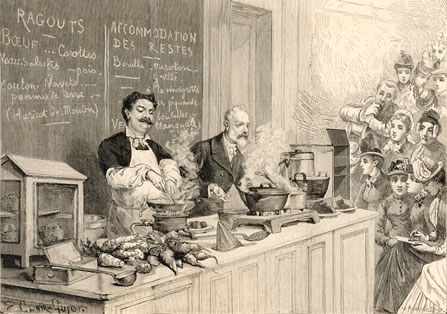

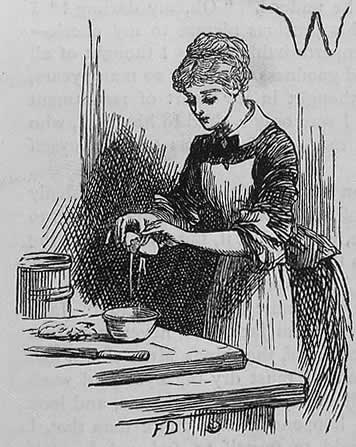

Even today, while watching Top Chef or Hell’s Kitchen, a female cook is rarely seen to raise her voice, shout and/or curse for her sous chefs and other underlings to get a move on. In vintage ads, a woman (frequently a mother) is posed in the kitchen with an apron, slaving lovingly over an apple pie or basting a turkey. For her, the kitchen is non-threatening; it is a place of peace and devotion; she is preparing a meal to nourish her family. The male in the kitchen is attired in chef’s clothing–tall white hat, white coat, dark pants. Frequently, his arms are crossed and he stares belligerently at the camera. Other times he is posed in the act of cutting, dicing, and mashing, and surrounded by a huge cavernous kitchen whose walls and ceilings are covered with big, heavy cast iron cookware.

Even today, while watching Top Chef or Hell’s Kitchen, a female cook is rarely seen to raise her voice, shout and/or curse for her sous chefs and other underlings to get a move on. In vintage ads, a woman (frequently a mother) is posed in the kitchen with an apron, slaving lovingly over an apple pie or basting a turkey. For her, the kitchen is non-threatening; it is a place of peace and devotion; she is preparing a meal to nourish her family. The male in the kitchen is attired in chef’s clothing–tall white hat, white coat, dark pants. Frequently, his arms are crossed and he stares belligerently at the camera. Other times he is posed in the act of cutting, dicing, and mashing, and surrounded by a huge cavernous kitchen whose walls and ceilings are covered with big, heavy cast iron cookware.

Interestingly enough, when the White House hired a new cook in 1910, Miss Flora Hamilton was replacing a woman who left the employ of the Presidential mansion to marry. It seems the White House long employed female cooks to prepare and direct the luxurious suppers over which the President and the First Lady hosted (which also brings the issue of race into play, as most White House staffers were African-American, and the image of “Mammy” lovingly preparing food for her employers in the kitchen remained in popular food culture for almost a century after the Civil War). She, however, like all female chefs, is consigned to the footnotes of history, to be unearthed only on accidental diggings through archives.

Further Reading:

The World of Escoffier by Timothy Shaw

The Art of Dining: A History of Cooking and Eating by Sara Paston-Williams

The Duchess of Jermyn Street: The life and good times of Rosa Lewis of the Cavendish Hotel by Daphne Vivian Fielding

The Queen of Cooks – and Some Kings: The Story of Rosa Lewis by Mary Lawton

Coming Out of the Kitchen: Women Beyond the Home by Una A. Robertson

Women As Culinary Professionals

Very interesting subject, and I’m going to rant a little now because this subject is one of my personal hot buttons. 😉

The whole men are chefs but women are merely cooks thing has always struck me as blatantly sexist. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for men who work in a “feminine” field to either be granted higher social status (i.e. chefs), or to be mocked for performing “women’s work” (i.e. nursing) based purely on their gender rather than their actual performance. And it bugs the hell out of me.

I like the point you make about men’s/women’s behavior in the kitchen. Society views it as perfectly acceptable for men to be aggressive and ruthless, but aggressive women are labeled “bitches.” As far as we’ve come, it’s still not socially acceptable for women to raise their voices, give orders, or be assertive. Which puts women at a distinct advantage in occupations where these behaviors are required to be successful.

I think it’s interesting to look at the history of many occupations with respect to gender, as you’ve done with cooking here, and see how they’ve changed. For example, working as a bank teller used to be a very prestigious, well-paid, and predominately male job. Once women started acquiring this position in larger numbers, both pay and prestige lowered considerably, and men either left the banking field entirely or moved up to fill almost all of the high-level positions.

Hey Katie, you aren’t alone in finding this to be a pet peeve. I can point to secretarial work and to telephone operators as positions formerly held by men and quickly “feminized” in the late 19th century. Whenever a woman in film/TV has a male secretary, he is either gay or the butt of the joke (hehe, a woman in charge!!). It is also interesting to note that when gender roles are reversed (like the aforementioned male secretary–though, I do notice that my placing “male” before the word “secretary” shows how unconsciously we place professions in certain genders) when the plot takes a romantic turn, the male remains in a position of power, and he serves to give the woman her comeuppance for daring to be in charge.

Great post! There is absolutely a sexual dichotomy in the kitchen, and I can’t help but wonder why that is. If you watch the cooking shows, almost all of the male celebrichefs talk about how their mothers were the ones who nurtured their love of cooking. Yet how many women are in their kitchen?

I agree that the absence of female chefs is remarkable, given that in that so many other professions we have gained ground. Have you read this interesting article in NY Magazine on the topic? http://nymag.com/restaurants/features/39595/

The female chefs illuminate the topic nicely. Vic

That’s a great article, Vic! Thanks!