The art/fashion of Yinka Shonibare, who melds 18th and 19th British aesthetics with “African” prints (his work is incredibly ironic and subversive; just looking at it makes me think) brought to mind the prints of Japanese women wearing Western fashions, yet made from Japanese textiles that I found online a few months ago. They were unaccompanied by text, so I did some digging, and found a few articles discussing the influence Japan (and the rest of Asia) had on America and Europe, and how America and Europe influenced Japan.

[flickr-gallery mode=”photoset” photoset=”72157626352074134″]

Images by Toyohara Chikanobu (豊原周延) (1838–1912), better known to his contemporaries as Yōshū Chikanobu (楊洲周延), a prolific woodblock artist of Japan’s Meiji period.

[source]The appearance of Western clothing and fashion during the Meiji era (1868 1912) represents one of the most remarkable transformations in Japanese history.

Since the United States’ 1854 treaty allowing commerce, negotiated by Commodore Matthew Perry, the Japanese have enthusiastically and effectively borrowed and adapted styles and practices from Western countries. Until then, Japan had isolated itself economically, politically, and culturally from the West as well as neighboring countries for two hundred years. The new Meiji era heralded hope for the future, and government officials felt change necessary for the system to quickly convert Japan into a modern state. Emperor Meiji instituted a parliamentary form of government and introduced modern Western educational and technological practices. The Japanese were then exposed widely to Western influences, and its impact on people’s lives has been impressive. This new modern phenomenon encouraged and expedited the spread of Western clothing among ordinary people, and it became a desirable symbol of modernization.

It was first adopted for men’s military uniforms, with French- and British-style uniforms designed for the army and navy, as this style was what Westerners wore when they first arrived in Japan. Similarly, starting in 1870, government workers, such as policemen, railroad workers, and postal carriers, were required to wear Western male suits. Even in the court of the emperor, the mandate to dress in Western clothing was passed for men in 1872 and for women in 1886. The emperor and empress, as public role models, took the lead and also adopted Western clothing and hairstyles when attending official events, and JAPANESE FASHION 260 Children in traditional Japanese costume. During the Meiji period, the T-shaped kosode became known as the kimono, and it is now recognized as the national dress of Japan. The hakama, as worn by the young boy, can be worn as an outer garment over the kimono.

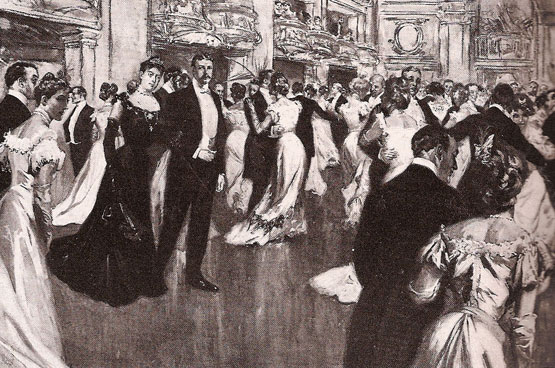

Japanese socialites were also participating in lavish balls in Western-style evening gowns and tuxedos. By the 1880s, both men and women had more or less adopted Western fashions. By 1890, men were wearing Western suits although it was still not the norm, and Western-style attire for women was still limited to the high nobility and wives of diplomats.

Kimonos continued to dominate in the early Meiji period, and men and women combined Japanese kimonos with Western accessories. For instance, for formal occasions, men wore Western-style hats with haori, a traditional waistcoat, hakama, an outer garment worn over the kimono that is either split like pants between the legs or nonsplit like a skirt. Conversely, there was also a trend for Japanese goods in the West. The opening of Japan’s doors to the West enabled the West to significantly come into contact with Japanese culture for the first time. New trade agreements beginning in the 1850s resulted in an unprecedented flow of travelers and goods between the two cultures. By the end of the nineteenth century, Japan was everywhere, such as in fashion, interior design, and art, and this trend was called Japonisme, a term coined by Philip Burty, a French art critic.

Western appreciation for Japanese art and objects quickly intensified, and World Fairs played a major role in the spread of the taste for Japanese things. In an age before the media, these fairs were influential forums for the cultural exchange of ideas: London in 1862, Philadelphia in 1876, and Paris in 1867, 1878, and 1889. Fashion after World War II During the Taisho period (1912 1926), wearing Western clothing continued to be a symbol of sophistication and an expression of modernity. It was in this period that working women such as bus conductors, nurses, and typists started wearing Western clothes in everyday life. By the beginning of the Showa period (1926 1989), men’s clothing had become largely Western, and by this time, the business suit was gradually becoming standard apparel for company employees. It took about a century for Western-style clothing for sale in Japan.

[source]Japanese adoption of Western dress

Cultural interaction is a two-way process.

It was during the Meiji period (1868-1912) that Japanese were first widely exposed to Western influences. By the 1880’s both men and women had adopted Western fashions. Western dress came to be seen as synonymous with modernity and many people adopted yofuku (western clothing). In the 1890’s, western suits were the norm for men; however, the Japanese women reverted to traditional Japanese clothing or wafuku. The only women who still wore Western fashion were the high nobility and wives of officials in foreign office. However, 40 years of Western fashion could not help but subtly influence the manner in which the kimono was worn. It unconsciously proclaimed Western elements while at the same time proclaiming its Japaneseness.

Western fashion influenced women’s kimono in two ways. The first is more obvious and relates to the adoption of physical items of dress such as coats, shawls, veils and jewelry. The second is more subtle; it changed notions of feminine beauty, caused the cultivation of clothing sensitivities, and promoted ideological aspirations concerning women in society.

The ideal body of the Western woman in the 1890-1900s was the S-curve. The corset compressed the waist, and caused the bosom to thrust forward and the hips back. The bustle accentuated the shaped behind, and the monobosom balanced it in front. This curvaceous form seems the opposite of the kimono’s straight lines. However, a very subtle penetration of this idealized form did occur in the shape of ladies’ wafuku even as Japanese women determined not to wear Western style dresses. During this time period, a boxy style of obi came into style, which if worn low, resembled a large, attached bustle. Thus, the kimono silhouette was very similar to the idealized Western silhouette.During the Taisho period (1912-1926) wearing Western apparel again became a sign of Western learning and an expression of modernity. Men began wearing business suits, which after W.W.II became commonplace for working men.

Women were slower to change. They retained the wafuku attire, but modified their elaborate hairdos slightly into the Gibson-girl bun. Additionally, changes occurred in the way the kimono was worn: (1) the kimono no longer trailed; the extra length was tucked under the obi; and (2) kimono gradually became more specialized in levels of formality. These were based on the types of fabrics used, style of obi knot, and the type of design used on the kimono.

Japan’s increased exposure to Western culture influenced kimono patterns and their colors in various ways. First, the patterns are no longer only of natural beauty, like trees and birds, but are often abstract designs. Second, the colors of the fabrics are no longer necessarily related to the age of the person who wears them. Once, a woman over thirty did not wear red or bright colors; today their is no special connection between the color and a person’s age. And third, the way of wearing the kimono has changed and become more contemporary. There are now two-pieced kimonos that are as easy to wear as blouses and skirts. Even “ready-to-wear” tied obi are available to put on like sash belts (Stevens and Wada, 1996).Japonisme

A strong American interest in Japanese handmade objects occurred as a result of two events: an international exposition in London in 1862 and the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. These two events launched a “Japan craze” in America – everyone was obsessed with things Japanese or things made in a Japanese style. The Kimono, viewed in America as the Japanese national dress, was a common motif of this popular movement which continued until the end of the 19th century.

To American women of the late 19th century, the kimono seemed the ideal model for a new American garment that allowed freedom of movement. The kimono contrasted sharply with the style of the day – stiff, multiple layers of petticoats and confining corsets. By the end of the 19th century, dress patterns of the kimono , or at least the American version of the Kimono, were available. American haute couture and lounge wear continued to be influenced by the kimono until as late as the 1920’s (Stevens and Wada, 1996).

American popular interest in the kimono diminished in the tense years prior to and during WW2. However, souvenir kimonos collected in great numbers by returning GI’s rekindled interest. (Stevens and Wada, 1996)

If you're new here, you may want to subscribe to my RSS feed, sign up for my newsletter, or like EP on Facebook. Love what you're reading? Has it helped your school project or book? Consider making a small donation to keep Edwardian Promenade online and a free resource in the years to come!

Thanks for visiting!

Fascinating post, Evangeline! The Yinka Shonibare dresses look incredibly ugly to me, but the book of Japanese-Western fashions was very cool. I’d never heard that the kimono was influenced by Western fashion, although it makes sense that it would be.

heidenkind,

“Evangeline” couldn’t have been suggesting that the Western World influenced the kimono…

The kimono had been an integral part of japanese fashion during the Edo period, in which Emporer Tokugawa Ieyasu specifically isolated Japan from the rest of the world. It was only in 1854 when the rest of the world was allowed limited commerce with Japan that western fashion leaked in. This specifically backs up my statement, “Kimonos continued to dominate in the early Meiji period…” The Meiji period was after Emporer Tokugawa’s fall in 1868.

Great post! I love the first book excerpt, but I don’t trust the 2nd book excerpt. Frankly, it sounds too simplistic and even a bit Orientalist! For example, the following section is what alarmed me:

“Women were slower to change. They retained the wafuku attire, but modified their elaborate hairdos slightly into the Gibson-girl bun. Additionally, changes occurred in the way the kimono was worn: (1) the kimono no longer trailed; the extra length was tucked under the obi; and (2) kimono gradually became more specialized in levels of formality. These were based on the types of fabrics used, style of obi knot, and the type of design used on the kimono.”

Women were slower to change not solely because they valued some nebulous Japanese traditions, but because newspapers, advertisements, school teachers, and even the government was actively pushing a “good wife, wise mother” ideology in which women were fashioned as the strongholds of traditional Japan. It isn’t necessarily that women did not want to change (as the author infers), but that they actually faced harassment if they wore Western style clothes! Newspaper columnists actually wrote articles about women who they saw wearing Western clothes in the 1910-1930s, saying that they were promiscuous and hedonistic!

“Japan’s increased exposure to Western culture influenced kimono patterns and their colors in various ways. First, the patterns are no longer only of natural beauty, like trees and birds, but are often abstract designs. Second, the colors of the fabrics are no longer necessarily related to the age of the person who wears them. Once, a woman over thirty did not wear red or bright colors; today their is no special connection between the color and a person’s age. And third, the way of wearing the kimono has changed and become more contemporary. There are now two-pieced kimonos that are as easy to wear as blouses and skirts. Even “ready-to-wear” tied obi are available to put on like sash belts (Stevens and Wada, 1996).”

From people I have talked with in Japan, those two-pieced kimonos mentioned above are actually seen as phenomena… I’ve only ever seen little children wear two-pieced informal kimono (yukata). Also, “ready-to-wear” tied obi are never used for formal occasion kimono, but only for yukata. And while exposure to the West did influence kimono patterns, I wouldn’t say that it was that people were attempting to emulate Westerners. Rather, the first designs that featured more abstract designs in the 1920s came about due to the industrialization of the kimono fabric-making processes (it was physically impossible with the technology back then to make the designs used in normal kimono).

The first source is great, and has some fabulous information, but the second source makes many blanket statements without explanation that just smacks of bad research… :/

Hi! Thanks for stopping by and lending your expertise. The inaccuracies and generalizations in the second really make me stop and think about how easy it is for Western scholars to make such sweeping statements because they will not be challenged for conforming to assumptions about non-Western societies and cultures.

Sure, no problem! I’m writing a paper on the subject of dress in Japan and how it ties in the women’s and men’s changing roles in society, so I really enjoy discussing the topic with others. In fact, searching for information led me to your post!

In fact, searching for information led me to your post!

I just have a quick question: do you know if the first source was just a blogger’s words, or did it come from a book? There’s some great information in there, but I can’t seem to find it anything but online encyclopedias, and the link is broken…

If you’re interested in learning more about 1920’s Japanese women’s fashion as impacted by the West, I would suggest reading Miriam Silverberg’s article, “The Modern Girl as Militant.” It’s a really great, clear explanation of the hype about hedonist, flapper-type women being the symbols of all that was wrong with modernity.

How cool. If you can share it, I’d love to read it when you’ve completed your paper!

Gah! I’m going to have to change the link since it’s broken…but I googled a few phrases from the text and came up with this pdf file and this archived website. The Library of Congress also has an online exhibit.

And thank you for the recommendation of Silverberg’s article, it sounds fascinating. Good luck with your paper!

Cool, that pdf file was just what I needed! Thanks for your help! ^_^

You’re welcome!

I’ll just leave my comment here. You can move it over there if you’d like.

It’s a beautiful post, with wonderful detail and analysis from a fashion-history perspective, with a dash of feminist theory or perspective thrown in. Great reading.

One commenter, kyle, however, has left some rather misleading information, which, as my focus of study is the Edo period, and foreign interactions in that period, strikes at a pet peeve of mine.

(1) Tokugawa Ieyasu was never Emperor. He was a Shogun, never challenged the Emperor for that title or position, i.e. for the throne, and in fact derived his power and legitimacy from the Emperor.

(2) Edo period Japan was not closed to the world. Under the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan restricted trade and access to the country to certain ports, and to certain trading partners, namely the Koreans via Tsushima, the Chinese and Dutch via Nagasaki, the Ryukyuans via Satsuma, and the Ainu via Matsumae.

Kyle writes that “It was only in 1854 when the rest of the world was allowed limited commerce with Japan that western fashion leaked in.” But he’s got it all turned around. It was *up until* 1854 that the world was allowed limited commerce, and that Western science, art, technology, fashion, political thought, etc. “leaked in”, and after 1854 that the gates were essentially thrown open, and Western everything began flooding in.

Thank you for this excellent post. I’ve linked to it and discussed it briefly on my own blog. And if you ever tackle Japanese topics again, I look forward to reading those posts. Cheers!