Long after the fame of the exclusive Gilded Age resort faded, the semi-formal suit (presently considered formal wear in America) which was lent its name remains. Prior to the 1880s, casual wear was rarely seen. For gentlemen, attire was dictated by the hour of day and destination. They looked to the English for evening dress, and despite the great difference in climate and temperament, Gilded Age gentlemen went stiffly to dinner in tails, waistcoat, and high collar. As high society looked to emulate their European betters, they began forming resorts–Newport was one, Bar Harbor, or Lakewood, New Jersey, were others, to name a few–where they could relax and play. Tobacco magnate Pierre Lorillard had other plans in mind when he sought to establish another aristocratic resort.

Long after the fame of the exclusive Gilded Age resort faded, the semi-formal suit (presently considered formal wear in America) which was lent its name remains. Prior to the 1880s, casual wear was rarely seen. For gentlemen, attire was dictated by the hour of day and destination. They looked to the English for evening dress, and despite the great difference in climate and temperament, Gilded Age gentlemen went stiffly to dinner in tails, waistcoat, and high collar. As high society looked to emulate their European betters, they began forming resorts–Newport was one, Bar Harbor, or Lakewood, New Jersey, were others, to name a few–where they could relax and play. Tobacco magnate Pierre Lorillard had other plans in mind when he sought to establish another aristocratic resort.

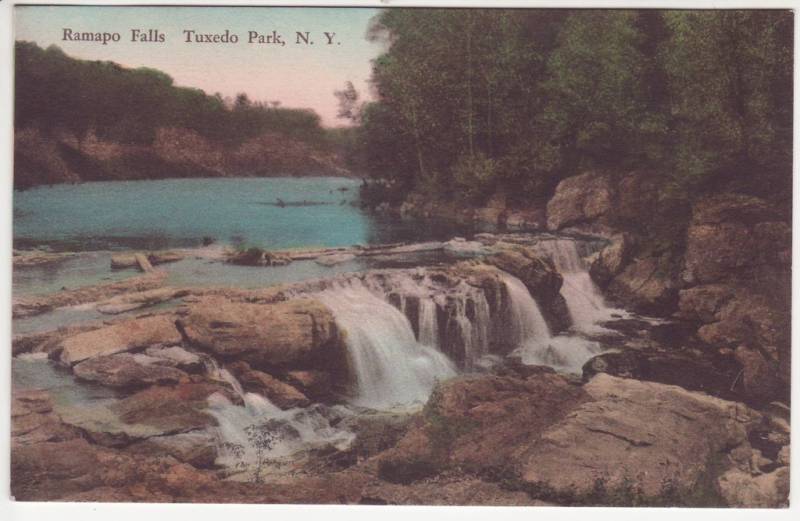

Where places like the aforementioned Newport, or Bar Harbor, sprang up around sleepy New England villages, and were easily accessed by the non-rich, Tuxedo Park was to be ultra-exclusive, man-made, and entirely unique. Through a combination of poker winnings and legitimate purchasing, Lorillard pieced together five thousand acres of land in the Ramapo Mountains region of Orange County, New York. At the urging of his lover, socialite-turned-actress Cora Brown Potter, he then turned the tract of land over to architect Bruce Price (the father of Emily Post) to design and build a gated community which would consist of luxurious cottages, private roads, a clubhouse, a private police station, and landscaping to mimic a rustic setting. Lorillard imported Italian and Slovak immigrants to build Tuxedo Park, and he rather thoughtlessly, but true to the period, named the shanties in which they lived “Fifth Avenue,” “Broadway,” and “Wall Street;” the workers mess hall was “Delmonico’s.”

Tuxedo Park opened in 1886, and members of the Four Hundred rushed to snap up land. However, those families who were not allotted  parcels on which to erect a cottage had to undergo a formal test before being allowed to buy land and build a home: first they contracted to buy land, at which point they were examined by the Tuxedo Association for admission to the club. If a prospective homeowner was denied admission to the club, their contract to buy property was simply voided. Nonresident members were permitted to stay in Tuxedo, but only for limited periods, and family members stayed in apartments on the top floors of the clubhouse, bachelors resided in a separate building, and families with children were housed in a separate building nicknamed “the baby kennels.” As Tuxedo Park was focused around the clubhouse, it was ruled with an iron fist by George Griswold, who created a set of rules and enforced them in a socially ruthless manner.

parcels on which to erect a cottage had to undergo a formal test before being allowed to buy land and build a home: first they contracted to buy land, at which point they were examined by the Tuxedo Association for admission to the club. If a prospective homeowner was denied admission to the club, their contract to buy property was simply voided. Nonresident members were permitted to stay in Tuxedo, but only for limited periods, and family members stayed in apartments on the top floors of the clubhouse, bachelors resided in a separate building, and families with children were housed in a separate building nicknamed “the baby kennels.” As Tuxedo Park was focused around the clubhouse, it was ruled with an iron fist by George Griswold, who created a set of rules and enforced them in a socially ruthless manner.

Laura Claridge describes the opening day on May 30, 1886 in Emily Post: Daughter of the Gilded Age, Mistress of American Manners:

[T]hree special trains, loaded with seven hundred guests, arrived from New York City. Green-and-gold buses and wagons, branding the scene with the club’s colors, lined up at the station to transport the visitors to the park. For latecomers, there were the Tuxedo taxicabs–single-horse covered carts, locally called “jiggers”–to pick up the slack.

Though Tuxedo Park was built as a sporting resort, its proximity to New York naturally incorporated a stay into the year-round social season–some families preferring to go there after the Newport season, instead of the Berkshires, and some even made Tuxedo their permanent residence. The year Tuxedo Park opened sparked not only the birth of the country club and modern American resort, but an item of clothing which was to change the way men dressed for formal events to this day.

Though Tuxedo Park was built as a sporting resort, its proximity to New York naturally incorporated a stay into the year-round social season–some families preferring to go there after the Newport season, instead of the Berkshires, and some even made Tuxedo their permanent residence. The year Tuxedo Park opened sparked not only the birth of the country club and modern American resort, but an item of clothing which was to change the way men dressed for formal events to this day.

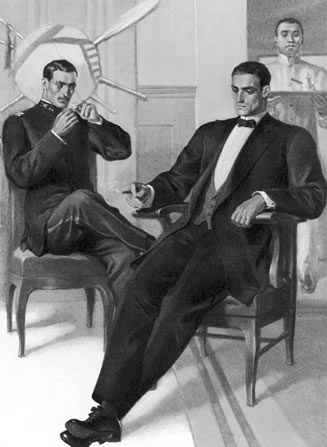

There are two accounts about the origins of the tuxedo. In one account, Pierre Lorillard’s son Griswold turned up in a tail-less evening jacket at Tuxedo Park’s annual Autumn Ball and apparently, the jacket became “known as the tuxedo when a fellow asked another at the Autumn Ball, ‘Why does that man’s jacket not have coattails on it?‘ The other answered, ‘He is from Tuxedo Park.’ The first gentleman misinterpreted and told all of his friends that he saw a man wearing a jacket without coattails called a tuxedo, not from Tuxedo.”

The other account gives the provenance of the tuxedo to fellow Tuxedo Park resident James Brown Potter, who brought a Homburg jacket made at Henry Poole & Co. home from a trip to England in 1886. When Potter and his friends wore this coat to a dinner party at Delmonico’s, it created a sensation and was dubbed a “tuxedo.” Whomever originated the tuxedo, its adoption over the tailcoat was considered daring until the Prince of Wales (later Duke of Windsor)–an ardent lover of all things American–made it acceptable for semi-formal evening dress. Though tie and tails prevailed for most, the younger generation preferred the tuxedo for its slightly informal aspect and its modernity.

Tuxes were considered informal? ROTFL

Thank god we got out of that habit. Baggy jeans and looking like you just rolled out of bed and pulled on whatever shirt your hand landed on FTW!

LOL. I take it you love that “Casual Fridays” are here to stay?

Once again, EP included some happenings on this side of the pond, but with references to the Old Country, to illustrate how the wealthy of both hemispheres inter-acted during the period. Keep up the good (and most interesting) work!