The ritual of taking tea in the “afternoon” (really, early evening, around four to five o’clock) conjures images of polite, white-gloved ladies gossiping over cups of steaming Oolong or Darjeeling. The ritual was established in the 1840s by the 7th Duchess of Bedford, who, finding herself famished between dinner and supper, “ordered a small meal of bread, butter, and other niceties, such as cakes, tarts, and biscuits, to be brought secretly to her boudoir. When she was exposed she was not ridiculed, as she had feared, but her habit caught on and the concept of a small meal, of niceties and perhaps tea, became popular and eventually known as ‘afternoon tea’.” As the century progressed, and cosmopolitan, aristocratic circles began to pattern itself after the Prince of Wales, the ritual of the afternoon tea began to be associated with more erotic elements, in the guise of the tea gown.

The ritual of taking tea in the “afternoon” (really, early evening, around four to five o’clock) conjures images of polite, white-gloved ladies gossiping over cups of steaming Oolong or Darjeeling. The ritual was established in the 1840s by the 7th Duchess of Bedford, who, finding herself famished between dinner and supper, “ordered a small meal of bread, butter, and other niceties, such as cakes, tarts, and biscuits, to be brought secretly to her boudoir. When she was exposed she was not ridiculed, as she had feared, but her habit caught on and the concept of a small meal, of niceties and perhaps tea, became popular and eventually known as ‘afternoon tea’.” As the century progressed, and cosmopolitan, aristocratic circles began to pattern itself after the Prince of Wales, the ritual of the afternoon tea began to be associated with more erotic elements, in the guise of the tea gown.

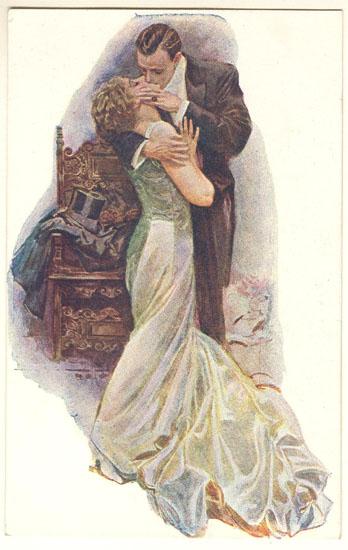

Alternately known as a “tea gown”, “robe d’interieur”, or as fashionable Edwardian society christened it, “teagie”, this article of clothing was, above all things, an indoor dress–as its name implies. A natural cousin to the dressing gown and the peignoir, both of which existed prior to the Edwardian era, the tea gown developed in the 1870s, when both day and evening dresses were tightly fitted. Enabling the Edwardian lady a chance to relax from the bustles and corsets of the day in the company of her associates, it was inevitable that the garment’s relative ease of fastening would prove itself the natural to the setting of seduction. Afternoon tea then morphed into what the French called “le fif-o’-clock” or “four to five”: the accepted time when a lady could entertain her lover with the tacit understanding of her husband. Said spouse would not enter the drawing room at that hour (and in fact, was most likely meeting his own lover), and with the collusion of discreet servants, the lady would announce herself “at home” to no one but her gentleman caller.

Alternately known as a “tea gown”, “robe d’interieur”, or as fashionable Edwardian society christened it, “teagie”, this article of clothing was, above all things, an indoor dress–as its name implies. A natural cousin to the dressing gown and the peignoir, both of which existed prior to the Edwardian era, the tea gown developed in the 1870s, when both day and evening dresses were tightly fitted. Enabling the Edwardian lady a chance to relax from the bustles and corsets of the day in the company of her associates, it was inevitable that the garment’s relative ease of fastening would prove itself the natural to the setting of seduction. Afternoon tea then morphed into what the French called “le fif-o’-clock” or “four to five”: the accepted time when a lady could entertain her lover with the tacit understanding of her husband. Said spouse would not enter the drawing room at that hour (and in fact, was most likely meeting his own lover), and with the collusion of discreet servants, the lady would announce herself “at home” to no one but her gentleman caller.

The gown itself, despite its naughty connotations, soon became a necessary part of a lady’s wardrobe, fashion writers of the day declaring that “no season’s outfit is considered complete without an assortment of tea gowns, and upon this costume designed and intended on for the most informal wear is expended more time and forethought and planning, that it may be perfect to the most minute detail, than is often given to a velvet reception gown or a satin ball dress.” Because of the gown’s marriage of both comfort and style, the costume moved also into the evening, a dinner tea gown, this version lower at the décolletage and made more elaborately, with somewhat the effect of a fitted gown with a loose cape of lace or chiffon worn over it. The train was longer and the sleeves shorter, and this gown is so made as to be suitable for an informal home dinner of not more than six persons, and was not meant to be worn outside one’s own house.

The gown itself, despite its naughty connotations, soon became a necessary part of a lady’s wardrobe, fashion writers of the day declaring that “no season’s outfit is considered complete without an assortment of tea gowns, and upon this costume designed and intended on for the most informal wear is expended more time and forethought and planning, that it may be perfect to the most minute detail, than is often given to a velvet reception gown or a satin ball dress.” Because of the gown’s marriage of both comfort and style, the costume moved also into the evening, a dinner tea gown, this version lower at the décolletage and made more elaborately, with somewhat the effect of a fitted gown with a loose cape of lace or chiffon worn over it. The train was longer and the sleeves shorter, and this gown is so made as to be suitable for an informal home dinner of not more than six persons, and was not meant to be worn outside one’s own house.

Of the afternoon tea gown, it was generally made with a transparent yoke of lace or chiffon, collarless and preferably slightly V-shaped. Soft silks and satins and penne and chiffon velvets were principally used for the afternoon tea gown, but chiffon, chiffon clothes, marquisette and lace were to be seen. By 1908, the tea gown was made in two parts, but instead of having waist and skirt separate, this part of the dress was all in one, while over it was slipped a loose coat or tunic of lace or chiffon transparent so as to leave visible the natural waistline. “The under part of the dress was composed of the skirt, which is generally elaborately flounced and trimmed, and a bodice made of the same material as the dress, but absolutely plain with ribbon or satin shoulder straps to keep the dress in place. The lace coats are apt to be the most effective if allowed to fall almost to the hem of the gown itself, the delicate shade of the silk or chiffon showing through the work of the lace with charming effect. A few of the tunics are of lace dyed the color of the chiffon or silk.”

A less romantic view was taken of this gown by French fashion writer, Baroness d’Orchamps, who suggested the tea-gown be worn for “messy chores or for visits to the kitchen.” Used for this sort of task, the gown would be made in wool, flannel, or broadcloth. But of course, this line of advice was ignored by the fashionable. The tea gown was suited to be an indoor garment, “born of fantasy,” and an original creation that was intended to express the wearer’s intimate tastes, while at the same time flattering to her beauty.

Further Reading:

The Book of Afternoon Tea by Lesley Mackley

Thanks for the great post on tea gowns. I have 3 of my characters wear elaborate tea gowns to afternoon tea at college in 1895, even though they weren’t really required. Loved the visual!

The French would actually call these afternoon love-making a “cinq à sept”, because it would take place at this time, the tea being served at five o’clock.

According to books I’ve used as reference, the phrase was directly culled from the English, so they said “Le fif o’clock” or “Le fif o’clock Anglais“. I’ll look into “cinq à sept.”

Wasn’t the old joke:

“It’s a tea dress. She wears it to teas.”

“To tease whom?”

I’m a professional French-English translator, have lived in France for ten years now, and have never heard of “le fif o’clock”. I realize Wikipedia isn’t a great reference, but it does confirm my own experience, which is that “le cinq à sept” is the common expression here. (Side note: just because the expression is common does not mean the practice is. In all my years here, I still don’t know a single couple that’s turned out to have a cheating partner, and I know hundreds of French people. Nor is cheating looked upon with any favor, despite what many reporters like to insinuate — it’s regarded much the same as anywhere else in the world: badly.)

Beyond that, it strikes me as very odd that it would be “fif”. “Five” is a numeral I’ve never heard mispronounced — the French get the “i” sound just right and the “v” too. Methinks your reference books are all quoting a single, unreliable source without necessarily realizing it…

fraise: are you sure it isn’t a colloquial way of expressing that time? Anglomania was pretty rife in aristocratic Paris, and the author of my main source (Cornelia Otis Skinner) was an expert on 1890s/1900s Parisian society. “Le Fif O’Clock” is used by Alice B. Toklas in her cookbook.

Y’all are confusing the French ‘Five o’clock’, which is when you have British-style tea and gossip with your girlfriends, and ‘le 5 a 7’ which is when you meet with your lover, who’s pleaded fatigue at the office for an early departure, and who’ll plead overwork at home when s/he gets there a bit late. Both are mercifully mostly historical artefacts, not common these days.

But fraise is misguided if she doesn’t know cheating people in contemporary France. The difference with the US is that it is regarded as bad form, and these days frequently leads to divorce, so people are discreet. Much more discreet than Americans can ever imagine. But that doesn’t mean it’s not happening.

Oh, and I could well believe Alice B making fun of French prononciation, which is still pretty atrocious, she probably did know someone saying feef o’cloque. But Fif wasn’t ever in general use.

there is a lot of reference to tea gowns in Proust, which is what led me to this site. Proust was a careful observers of custom, and especially of liaisons, adulterous, seductive and otherwise. in Proust tea gowns seem to be worn at home and in the early evening. They are not exclusively associated with entertaining one’s lover; they are often worn when the hostess is recieving her women friends.

Hi Tony, yes indeed tea gowns were worn for casual gatherings with friends, but the general aura around the item of clothing was one of seduction. After all, before its invention, women of the 19th century did not wear such relaxing, available clothing in informal settings.