Inside the closet of any proper fashionable woman is a little black dress–that dependable, simple frock which looks both dressy and casual depending on the occasion. Though the color had long been associated with mourning, Edwardian couturiers, in quest of anything new and innovative, lately snatched upon the notion of wearing black in sumptuous day and evening wear. From around 1909 to 1914, ladies increasingly turned to black or black-and-white gowns for simplicity and freshness. According to Anne Rittenhouse, the fashion editor for the New York Times in the Edwardian era, “a judicious selection of cut and material in a black gown will serve for walking, for afternoon calls, for luncheons, the matinee, and large teas. For exclusive luncheons, wedding breakfasts and receptions, for dinners are restaurants, and for receiving at an afternoon tea, the gown must be made of different material, even if on the same model.”

Inside the closet of any proper fashionable woman is a little black dress–that dependable, simple frock which looks both dressy and casual depending on the occasion. Though the color had long been associated with mourning, Edwardian couturiers, in quest of anything new and innovative, lately snatched upon the notion of wearing black in sumptuous day and evening wear. From around 1909 to 1914, ladies increasingly turned to black or black-and-white gowns for simplicity and freshness. According to Anne Rittenhouse, the fashion editor for the New York Times in the Edwardian era, “a judicious selection of cut and material in a black gown will serve for walking, for afternoon calls, for luncheons, the matinee, and large teas. For exclusive luncheons, wedding breakfasts and receptions, for dinners are restaurants, and for receiving at an afternoon tea, the gown must be made of different material, even if on the same model.”

In a 1911 article, the correspondent for The Daily Graphic remarked: “Women are to be fantasies of black and white. This lack of color was in vogue last Winter, but the combination has now developed into the wildest eccentricities:”

With a white satin gown were worn black furs, white silk stockings, and black shoes

A frock of white silk velvet brocade, over which was worn a mantle cloak of black chiffon and musquash

A black gown was heavily embroidered with white knitted worsted, while another was edged around the hem of the short ankle skirt with tiny black silk fringes, through which were visible when the wearer walked the white uppers of black patent-leather boots.

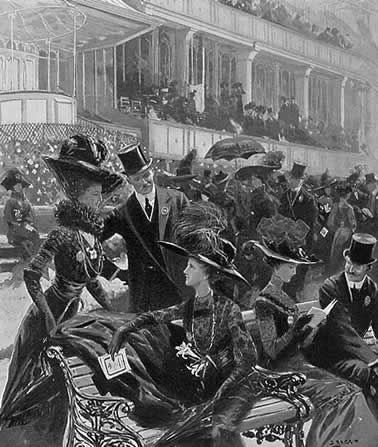

The most famous occasion of black attire was “Black Ascot”–that week in 1910 where Society attended the races (at the behest of King George V) in mourning to honor King Edward VII, who died that May. Ultimately, Black Ascot, and the trend for black-and-white gowns at the end of the Edwardian era, inspired Cecil Beaton’s infamous Ascot sequence in My Fair Lady.