In a manner, the dandy was the male counterpart of the professional beauty: he had no other occupation than to devote himself to being clever, witty, well-dressed and amusing. Much like the Regency dandy, the Edwardian version flourished in an era where birth and breeding were no longer indicative of entrance into exclusive circles of society.

In England, King Edward set the standard by his attention to the finer details of dress. So acute were his sensibilities, he was not above rebuking a subject for not appearing up to date: as in the case of the Marquess of Salisbury, who, rushing to a Drawing Room and dressing without his valet, horrified the Prince of Wales by his haphazard attire (according to an account, Lord Salisbury ironically replied, “It was a dark morning, and I am afraid that at the moment my mind must have been occupied by some subject of less importance.”), or with the American-born Duchess of Marlborough, who was coldly rebuked by the king when she appeared at a supper wearing diamond combs in her hair instead of a tiara, like the Queen (to this, Consuelo quietly answered she had little time to change, having hurried home from a charity event). Under his aegis, it was very important to know exactly when to wear the right clothes, as any departure from the norm was regarded as a social gaffe.

As such, the 1880s and 1890s found dandyism once more of good repute. The English dandy oddly enough, was most likely found in the Houses of Parliament. With the exception of W.E. Gladstone, new standards of sartorial elegance were set, most notably by Lord Randolph Churchill and Joseph Chamberlain, whose image became synonymous with the ever-present monocle, silk hat and orchid boutonnière he wore. On stage, the plays of Shaw, Pinero and Wilde demanded super-fine, even fantastical costumes for the male characters, and the “fashionable novel,” which depicted the lives of the upper classes, made a triumphant return, and every one had its chorus of showy dandies. In 1889, the London weekly, Vanity Fair, debuted a new column, “The Fashion for Men” by “the Man in the Mall”, whose author wrote detailed recommendations for “stiff collars, velvet bands, true and false waistcoats, peg-top trousers, yellow gloves, gilded sticks, and violet boutonnières”.

The most notorious dandy of this period was, of course, Oscar Wilde. His early years were spent in the standard clothing of a middle-class young man: tiny Bowler tipped rakishly over a brow, bright tweeds and comfortable trousers, waistcoat and jacket. By the end of his term at Oxford, he set himself on the path to becoming “Professor of Aesthetics” and dressed the part in knee breeches, a flowing tie, velvet coat, wide, turned-down collar, and a drooping lily. Laying siege to London society, he quickly conquered such notables as Henry Irving, Sarah Bernhardt, Lillie Langtry and Ellen Terry, among others, by writing them countless invitations to supper, flower arrangements and requests for photographs. These celebrities, and anyone with which they associated, were news, and by 1880, two years after Wilde came down from Oxford, he was a star. Moving from strength to strength in the ’80s, by the wit of his pen and sweat of his violet-scented brow, Wilde’s plays reached the stage, and to wild success. As he achieved both financial security and creative success, his style of dress changed from that of languid Aesthete to the florid Regency-era dandy. In the ’90s, fame, brought about by his plays, replaced the trivial notoriety of his earlier years, and his dress became coldly correct, Wilde expressing his individuality with a single detail: a green boutonnière, a bright red waistcoat, or a turquoise and diamond stud.

The most notorious dandy of this period was, of course, Oscar Wilde. His early years were spent in the standard clothing of a middle-class young man: tiny Bowler tipped rakishly over a brow, bright tweeds and comfortable trousers, waistcoat and jacket. By the end of his term at Oxford, he set himself on the path to becoming “Professor of Aesthetics” and dressed the part in knee breeches, a flowing tie, velvet coat, wide, turned-down collar, and a drooping lily. Laying siege to London society, he quickly conquered such notables as Henry Irving, Sarah Bernhardt, Lillie Langtry and Ellen Terry, among others, by writing them countless invitations to supper, flower arrangements and requests for photographs. These celebrities, and anyone with which they associated, were news, and by 1880, two years after Wilde came down from Oxford, he was a star. Moving from strength to strength in the ’80s, by the wit of his pen and sweat of his violet-scented brow, Wilde’s plays reached the stage, and to wild success. As he achieved both financial security and creative success, his style of dress changed from that of languid Aesthete to the florid Regency-era dandy. In the ’90s, fame, brought about by his plays, replaced the trivial notoriety of his earlier years, and his dress became coldly correct, Wilde expressing his individuality with a single detail: a green boutonnière, a bright red waistcoat, or a turquoise and diamond stud.

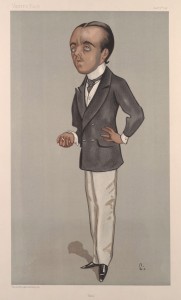

Caricatures of Max Beerbohm show him attired in a high stiff collar, gloves, a carefully tilted silk hat, a cane, a boutonnière, an artfully bulging frock coat, and tapering trousers–the basic equipment for the ’90s dandy of the most correct school. A contemporary of Wilde’s, and half-brother to celebrated actor Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Max Beerbohm exemplified the Edwardian dandy. As befitting a proper dandy of this period, he was in much demand as a guest at the great dinner parties of Mayfair, where he was considered by many to be the greatest wit in town. His inspiration came directly from Brummell and D’Orsay, and as the era experienced a revival in the 1880s and 1890s, materializing in numerous plays, and reprinted memoirs and biographies,it was as “prophet” of the English Regency that his reputation was made.

Caricatures of Max Beerbohm show him attired in a high stiff collar, gloves, a carefully tilted silk hat, a cane, a boutonnière, an artfully bulging frock coat, and tapering trousers–the basic equipment for the ’90s dandy of the most correct school. A contemporary of Wilde’s, and half-brother to celebrated actor Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Max Beerbohm exemplified the Edwardian dandy. As befitting a proper dandy of this period, he was in much demand as a guest at the great dinner parties of Mayfair, where he was considered by many to be the greatest wit in town. His inspiration came directly from Brummell and D’Orsay, and as the era experienced a revival in the 1880s and 1890s, materializing in numerous plays, and reprinted memoirs and biographies,it was as “prophet” of the English Regency that his reputation was made.

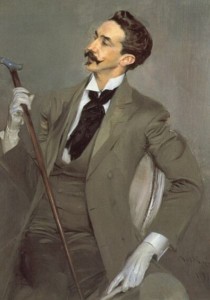

Across the Channel, the French dandy was personified in many of le gratin‘s gentlemen, most notably Comte Robert de Montesquiou and Comte Boni de Castellane. Both gentlemen were members of France’s most elite aristocracy, and both had a reputation for decadence and bizarre ostentation. The favorite subject of Comte Robert de Montesquiou was himself, and his vanity prompted him to commission innumerable portraits of himself. To any criticism, he was indifferent, saying “It is better to be hated than to be unknown.” Descending from the  dukes of Gascony and the Merovingian kings, he was exceedingly proud of his royal connections and, sublimely self-assured, he held sway over a worshipful band of muses, literary ladies and young Symbolists. He selected his costume based upon his moods, and could turn up in sky-blue, or his famous almond-green outfit with a white velvet waistcoat. His collection of scarf pins was notorious; ranging in motif from an emerald butterfly to an onyx death’s head. On a finger, he wore a large signet ring with a crystal hollowed out to contain one human tear. Adding to this affectation was Comte Robert’s place of residence. Living on the top floor of his father’s hotel prive, his remote suite of rooms were reached by climbing a dark, twisting staircase and passing through a carpeted tunnel lined with tapestry. In this suite were fantastical rooms decorated by his various moods: a pink room, a gray room (for which he ransacked flower stalls daily for gray flowers), a room featuring a Russian sleigh and polar-bear rug, and a library housed in a glass conservatory.

dukes of Gascony and the Merovingian kings, he was exceedingly proud of his royal connections and, sublimely self-assured, he held sway over a worshipful band of muses, literary ladies and young Symbolists. He selected his costume based upon his moods, and could turn up in sky-blue, or his famous almond-green outfit with a white velvet waistcoat. His collection of scarf pins was notorious; ranging in motif from an emerald butterfly to an onyx death’s head. On a finger, he wore a large signet ring with a crystal hollowed out to contain one human tear. Adding to this affectation was Comte Robert’s place of residence. Living on the top floor of his father’s hotel prive, his remote suite of rooms were reached by climbing a dark, twisting staircase and passing through a carpeted tunnel lined with tapestry. In this suite were fantastical rooms decorated by his various moods: a pink room, a gray room (for which he ransacked flower stalls daily for gray flowers), a room featuring a Russian sleigh and polar-bear rug, and a library housed in a glass conservatory.

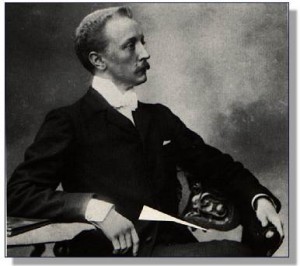

Though his wife was extremely plain, Anna Gould had a dowry of fifteen million dollars. Bolstered by this, Boni de Castellane devoted himself to the art of dandyism, spending those millions lavishly on the construction of the Palais Rose, a pink marble palace in the Avenue du Bois fitted with a staircase as grand as that of the Opera, an immense ballroom and a private theatre with five hundred seats; maintaining two châteaux in the country, a villa at Deauville and a 1600-ton yacht; buying priceless works of art; and becoming the best dressed man in Europe. Despite his spendthrift behavior, Comte Boni was a person of polish and culture, who could converse on any subject. His only crime was to have been born in the wrong century, for he adored the court of eighteenth century Versailles, and did anything to recreate the bygone era. His reign came to an abrupt end, however, in 1906 when he arrived home to discover the electricity out. After eleven years of marriage, five children and the spending of $10 million of her dowry, Anna Gould had filed for divorce. She cut off his funds, threw him out of his houses and sent his clothes, his only remaining fortune, to him in care of his parents and shortly thereafter, married his cousin.

art of dandyism, spending those millions lavishly on the construction of the Palais Rose, a pink marble palace in the Avenue du Bois fitted with a staircase as grand as that of the Opera, an immense ballroom and a private theatre with five hundred seats; maintaining two châteaux in the country, a villa at Deauville and a 1600-ton yacht; buying priceless works of art; and becoming the best dressed man in Europe. Despite his spendthrift behavior, Comte Boni was a person of polish and culture, who could converse on any subject. His only crime was to have been born in the wrong century, for he adored the court of eighteenth century Versailles, and did anything to recreate the bygone era. His reign came to an abrupt end, however, in 1906 when he arrived home to discover the electricity out. After eleven years of marriage, five children and the spending of $10 million of her dowry, Anna Gould had filed for divorce. She cut off his funds, threw him out of his houses and sent his clothes, his only remaining fortune, to him in care of his parents and shortly thereafter, married his cousin.

The outbreak of the Great War brought la belle epoque to an abrupt end, and with it, the dandy. Certainly gentlemen since have cared greatly for their appearance, but the art, the cultivation of it, and even the acceptance and admiration of it by both men and women, seems strictly the province of the long nineteenth century.

Further Reading:

The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm by Ellen Moers

Dandies and Desert Saints: Styles of Victorian Masculinity by James Eli Adams

Dandies by James Laver

Theatre and Fashion: Oscar Wilde to the Suffragettes by Joel H. Kaplan and Sheila Stowell

Dressed to Rule: Royal and Court Costume from Louis XIV to Elizabeth II by Philip Mansel

Greetings to you:

I like to express my delight after reading your work. I have to say Beerbohm gets the nod.

Good day.

Thank you for stopping by! And I like Beerbohm as well! 😉