Unlike women’s fashions, traditional articles of gentleman’s clothing changed very little; the only concession to the passing of time were tiny details: a new cut to trousers, a new shape to a jacket, etcetera. As it had since the turn of the nineteenth century, colors remained fairly dark, the only places allotted for color, the waistcoat, the sweater and the tie. However, with the rise of sports such as hunting, yachting, cricket, polo and others, there came the introduction of sportswear. As with most things pertaining to the Edwardian era, the Prince of Wales heavily influenced not only what men wore, but when.

Unlike women’s fashions, traditional articles of gentleman’s clothing changed very little; the only concession to the passing of time were tiny details: a new cut to trousers, a new shape to a jacket, etcetera. As it had since the turn of the nineteenth century, colors remained fairly dark, the only places allotted for color, the waistcoat, the sweater and the tie. However, with the rise of sports such as hunting, yachting, cricket, polo and others, there came the introduction of sportswear. As with most things pertaining to the Edwardian era, the Prince of Wales heavily influenced not only what men wore, but when.

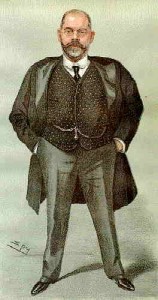

For day, morning dress was de rigueur. To be seen in London attired in nothing less was an affront to sartorial sensibilities. Morning dress consisted of a morning coat, which was almost always single-breasted, of serge, worsted, cheviot or vicuna, and black or iron-gray; a waistcoat, either single- or double-breasted, which matched the coat or was of a lighter color; striped spongebag trousers (trousers of wool serge, baggy at knee); a cravat; and silk hat (though a bowler/Homburg could be worn). The frock coat, a double-breasted, knee-length coat of black or dark gray wool, was worn on formal morning occasions, though by the Edwardian era, it was more often seen on elderly men. By the 1900s, the lounge jacket began to replace both the morning coat and frock coat. Generally high of neck, with short lapels and double-breasted, the front curved away at the bottom.

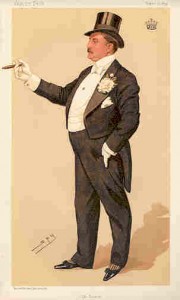

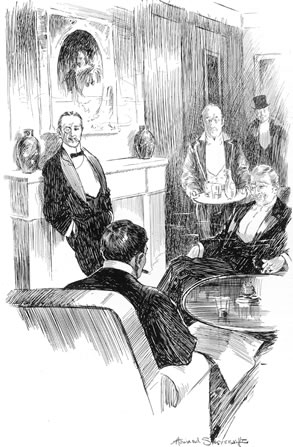

For evening, men’s attire was strictly composed of a black dress coat, white waistcoat and trousers matching the coat. The dress coat was double-breasted with a cut-away front and two tails at the rear. In 1900, the tails were knee length and the front cut away square at the waist, with two or three buttons on each front. The sleeves would end plain or with a cuff, and slit with two or three buttons also. There was also the choice to wear the dinner jacket if dressing for dinner at home or at a men’s club. This was worn with a white shirt and a dark tie. As the era progressed, the dinner jacket was increasingly cut on the lines of a lounge jacket, and from it emerged the “tuxedo” (though this was the American term; the Continental term was “Monte Carlo”).

For evening, men’s attire was strictly composed of a black dress coat, white waistcoat and trousers matching the coat. The dress coat was double-breasted with a cut-away front and two tails at the rear. In 1900, the tails were knee length and the front cut away square at the waist, with two or three buttons on each front. The sleeves would end plain or with a cuff, and slit with two or three buttons also. There was also the choice to wear the dinner jacket if dressing for dinner at home or at a men’s club. This was worn with a white shirt and a dark tie. As the era progressed, the dinner jacket was increasingly cut on the lines of a lounge jacket, and from it emerged the “tuxedo” (though this was the American term; the Continental term was “Monte Carlo”).

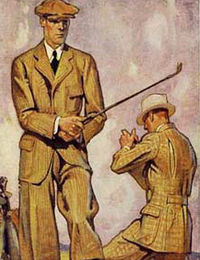

Due to Bertie’s fondness for lounge suits, sport jackets, Norfolk shooting jackets with front and back pleats, and knickerbockers in loud tweeds, there came a greater emphasis on comfort, and a greater obsession with sports. This was the epoch of polo, cricket, shooting and hunting, and in the 1890s, such new sports such as tennis, football, golf, cycling and motoring. And of course each sport required its own set of clothing. Knits, flannel and tweeds were popular, with the color white most used for yachting, golf, tennis, cricket and polo. For cycling, shooting and golf, knickerbockers and plus-fours, a type of loose knee-breeches fastened at the knee with a band were favored, and for rowing, knit sweaters in team or school colors (e.g. light blue for Cambridge, navy for Oxford).

Due to Bertie’s fondness for lounge suits, sport jackets, Norfolk shooting jackets with front and back pleats, and knickerbockers in loud tweeds, there came a greater emphasis on comfort, and a greater obsession with sports. This was the epoch of polo, cricket, shooting and hunting, and in the 1890s, such new sports such as tennis, football, golf, cycling and motoring. And of course each sport required its own set of clothing. Knits, flannel and tweeds were popular, with the color white most used for yachting, golf, tennis, cricket and polo. For cycling, shooting and golf, knickerbockers and plus-fours, a type of loose knee-breeches fastened at the knee with a band were favored, and for rowing, knit sweaters in team or school colors (e.g. light blue for Cambridge, navy for Oxford).

Typical outwear consisted of the Chesterfield, a single-breasted coat of herringbone tweed with velvet collar; the ulster, a slightly less-fashionable coat with shoulder cape or hood generally worn for travel; the Raglan overcoat, a long and full coat of waterproof material, made with side seams to allow access to trouser pockets; the Inverness cape, a waterproof coat with a cape-like front composed of two “wings” taking the place of sleeves and covering the arms–made of fur or fur-lined for motoring; and mackintoshes, a raincoat of rubber, tweed, cotton, parramatta, etc. Made of gabardine, the trench coat, was invented by Thomas Burberry in 1901 as an alternative to the heavy serge greatcoats worn by British and French officers. Though not in widespread use until the Great War, it was an optional piece included in a typical officer’s kit.

Raglan overcoat, a long and full coat of waterproof material, made with side seams to allow access to trouser pockets; the Inverness cape, a waterproof coat with a cape-like front composed of two “wings” taking the place of sleeves and covering the arms–made of fur or fur-lined for motoring; and mackintoshes, a raincoat of rubber, tweed, cotton, parramatta, etc. Made of gabardine, the trench coat, was invented by Thomas Burberry in 1901 as an alternative to the heavy serge greatcoats worn by British and French officers. Though not in widespread use until the Great War, it was an optional piece included in a typical officer’s kit.

Hats were also dictated by fashion and time of day. Casual hats for the day included the Homburg, a stiff felt hat with a dented crown and turned-up silk-bound brim; the Trilby, of a similar shape but with a softer felt; and the Derby (Bowler in  America), with either curved or flat sides. The top or silk hat was worn with the frock coat, morning coat and evening dress, but as the first two were replaced by the lounge suit, the top hat was less seen in the streets; the boater, a flat-brimmed, flat-crowned straw hat worn in the summer; and the opera hat, also known as a “Gibus” after its inventor. This hat was of corded silk or merino and the crown was supported by a spiral spring that enabled the hat to collapse and fold quite flat.

America), with either curved or flat sides. The top or silk hat was worn with the frock coat, morning coat and evening dress, but as the first two were replaced by the lounge suit, the top hat was less seen in the streets; the boater, a flat-brimmed, flat-crowned straw hat worn in the summer; and the opera hat, also known as a “Gibus” after its inventor. This hat was of corded silk or merino and the crown was supported by a spiral spring that enabled the hat to collapse and fold quite flat.

The “tooth-pick“, a shoe of black or tan with a long pointed toe, was worn, though boots were correct for dress wear. From 1910 on, shoes became more popular than boots, and about this year, the American Boston, or bull-dog toe was introduced. This had a blunt round toe with an upward bulge. Accessories for men included gloves, spats, scarves, umbrellas, walking sticks and various items of jewelry. Gloves were essential for town wear, of tan kid for day, and suede or fabric for evenings. Scarves were of knitted silk or wool; some plainly colored,

boots, and about this year, the American Boston, or bull-dog toe was introduced. This had a blunt round toe with an upward bulge. Accessories for men included gloves, spats, scarves, umbrellas, walking sticks and various items of jewelry. Gloves were essential for town wear, of tan kid for day, and suede or fabric for evenings. Scarves were of knitted silk or wool; some plainly colored,  some striped. Spats of drill or box-cloth were in black, drab or white, and covered the top of shoe and ankle, fastened with four buttons and a strap and buckle under the foot. The umbrella, when tightly rolled, doubled for a walking stick, and during the 1890s, became a fashionable substitute for it. Walking sticks of malacca and rattan were favorites for Town use, with crook, crutch or straight handles, very often mounted with silver bands and tips. Some sticks cleverly held in their recesses pencils, cigarettes, flasks, pipes or even devices for measuring the height of horses.

some striped. Spats of drill or box-cloth were in black, drab or white, and covered the top of shoe and ankle, fastened with four buttons and a strap and buckle under the foot. The umbrella, when tightly rolled, doubled for a walking stick, and during the 1890s, became a fashionable substitute for it. Walking sticks of malacca and rattan were favorites for Town use, with crook, crutch or straight handles, very often mounted with silver bands and tips. Some sticks cleverly held in their recesses pencils, cigarettes, flasks, pipes or even devices for measuring the height of horses.

Watches were of the pocket type, open faced, half-hunter and full-hunter cases (with the glass protected by a metal cover; the half-hunter had a circular cut-out in the middle of the cover, with the hour chapters engraved around it; the hands could be partially seen through this cut out). They were made of gold, silver, nickel and oxidized steel. Matching Albert chains passed across the waistcoat, through a chain-hole, and the watch was placed in one pocket, the other end of the chain in the other. Pins were of gold for ties and scarves, and made in many shapes. In gold or silver also, were cigarette cases and visiting card cases. Leather wallets, note cases (for pound notes) and purses were also worn by men. To round off other accessories were cuff links, key-rings, silver match-boxes, petrol and tinder lighters, cigar and cigarette holders of meerschaum or amber, and pipes and tobacco pouches were carried from time to time.

the glass protected by a metal cover; the half-hunter had a circular cut-out in the middle of the cover, with the hour chapters engraved around it; the hands could be partially seen through this cut out). They were made of gold, silver, nickel and oxidized steel. Matching Albert chains passed across the waistcoat, through a chain-hole, and the watch was placed in one pocket, the other end of the chain in the other. Pins were of gold for ties and scarves, and made in many shapes. In gold or silver also, were cigarette cases and visiting card cases. Leather wallets, note cases (for pound notes) and purses were also worn by men. To round off other accessories were cuff links, key-rings, silver match-boxes, petrol and tinder lighters, cigar and cigarette holders of meerschaum or amber, and pipes and tobacco pouches were carried from time to time.

Further Reading:

Handbook of English costume in the nineteenth century by C. Willett Cunnington

Handbook of English Costume in the 20th Century 1900-1950 by Alan Mansfield and Phillis Cunnington

Men’s Fashion Illustrations from the Turn of the Century by Mitchell Co. and Jean L. Druesedow

Thanks for the information. I was actually checking this article when doing some research for a painting I wanted to do involving an Edwardian style costume.