No one in the Edwardian era made any bones about the fact that marriage was a woman’s sole career, and that she owed it to herself and to the family that had so far supported her, to get on with it. Where a girl was concerned, it was the duty of everyone–her mother, her mother’s friends, her chaperone and her bill-settling father–to help her achieve this ambition.

No one in the Edwardian era made any bones about the fact that marriage was a woman’s sole career, and that she owed it to herself and to the family that had so far supported her, to get on with it. Where a girl was concerned, it was the duty of everyone–her mother, her mother’s friends, her chaperone and her bill-settling father–to help her achieve this ambition.

Once a young girl turned eighteen, her childhood was essentially over. The moment she put up her hair and lengthened her skirts, she was a woman. A coddled and protected woman, but a woman nonetheless. The putting up of the hair was the most important aspect of signifying one’s status as a jeune fille à marier, or a young woman ready for marriage: no man bothered to address himself with other than the merest passing courtesy to a girl whose hair hung down her back. As soon as her hair was pinned up, everything changed, and for the remainder of the young lady’s life, her hair would hang down over her shoulders only inside her bedroom or at a fancy dress ball.

An American debutante’s entrance into society was marked by the order of dresses from Paris, a ball at Delmonico’s or at home, and the most extensive leaving of cards on all desirable acquaintances. In introducing a daughter, parents seldom put her name on the card, merely sending invitations written thus:

Mrs. Walsingham

at home,

Thursday evening, February 9th,

at ten o’clock

At her first ball, the American debutante stood beside her mother, was presented to the guests, and was then introduced to and danced the German with the gentleman to whom her mother had selected to lead the dance—and that was it. In the 1890s, the Four Hundred attempted incorporate the chaperone from Europe, to much controversy. America at the time prided itself upon the ability of a woman to move about unmolested. The presence of a chaperone was a smack in the face to the American gentleman: were they not be trusted? The fierce independence of Americans won out in the end, and the custom of chaperonage died a quick, painless death by the turn of the century.

At her first ball, the American debutante stood beside her mother, was presented to the guests, and was then introduced to and danced the German with the gentleman to whom her mother had selected to lead the dance—and that was it. In the 1890s, the Four Hundred attempted incorporate the chaperone from Europe, to much controversy. America at the time prided itself upon the ability of a woman to move about unmolested. The presence of a chaperone was a smack in the face to the American gentleman: were they not be trusted? The fierce independence of Americans won out in the end, and the custom of chaperonage died a quick, painless death by the turn of the century.

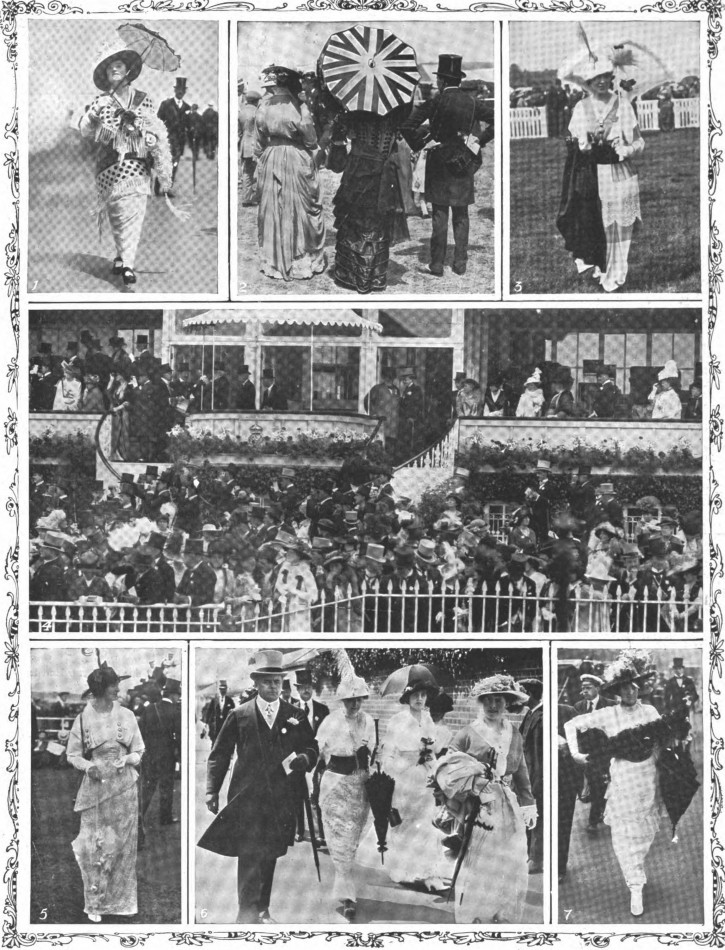

The English debutante’s entrance into society was marked in a few ways: the court presentation, a supper party, or a country ball. In some unorthodox families, such as the Tennants, young ladies were permitted to take part in social events as young as 15 or 16. The young men whom they might meet were always carefully inspected and discussed beforehand by their mothers, aunts, grandmothers–and indeed the whole circle of older ladies. Meetings were seldom, if ever, mere chance: daughters who might be expected to become a good political hostess were deliberately placed in the way of eligible political bachelors, and young daughters of great landed estates who would expect to live in the country were steered towards gentlemen with great landed estates. The acceptable choice was limited, but quite clear.

Gentlemen were placed into types: if the young lady met a “detrimental,” or extremely ineligible man, her female relations would gently remind her of her duty. There was less to fear from the “indefatigable,” a young man just come out or an old beau who danced indiscriminately with any and all women, or from the “indispensable,” the anxious fetcher and carrier of wraps, gloves, lemonade, fans and ices, but a young lady was introduced to as many approved and eligible men as quickly as possible.

The French, however, were a bit more cerebral when it came to the debutante. To be considered an eligible young woman, one must have a dot, or dowry. Those who were not provided for were doomed to be spinsters or poor relations, and as a result, most convents were packed not with devout novitiates, but poor young women. Not to say there were no “love matches” amongst the French, but it was rare amongst the nobility, for whom marriage was too serious a matter to be dominated by romantic notions. After emerging from a convent school, the French debutante was introduced at a bal blanc, at which all ladies were gowned in pure white and only maidens and bachelors were expected to be present. There, the gentlemen were permitted to request to dance with a lady without having been first introduced to her, and it was considered very bad form for a young woman and young man to “sit out” a dance together or to retire to the veranda or lawn.

The French, however, were a bit more cerebral when it came to the debutante. To be considered an eligible young woman, one must have a dot, or dowry. Those who were not provided for were doomed to be spinsters or poor relations, and as a result, most convents were packed not with devout novitiates, but poor young women. Not to say there were no “love matches” amongst the French, but it was rare amongst the nobility, for whom marriage was too serious a matter to be dominated by romantic notions. After emerging from a convent school, the French debutante was introduced at a bal blanc, at which all ladies were gowned in pure white and only maidens and bachelors were expected to be present. There, the gentlemen were permitted to request to dance with a lady without having been first introduced to her, and it was considered very bad form for a young woman and young man to “sit out” a dance together or to retire to the veranda or lawn.

Prior to this ball, the French debutante was invited nowhere and met no gentleman, since amusements and flirtations were considered the sole province of a married woman. Young men were hampered by this restriction as well, for they were honor-bound never to court a girl without having previously asked her parents’ permission. As the slightest attention to a girl was immediately assumed to be a serious declaration, the young man was supposed to ask this permission before knowing his bride or risk being shot by her brother should he afterward decline marrying within a few weeks’ notice.

Even stricter were the lives of debutantes in Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary. The daughters of Russia’s nobility were entered into one the of the numerous educational establishments founded for the their training as early as age three, and there they remained until seventeen. At The Catherine Institution, one of the principal rules was that from the time a pupil entered the school until her sortie, she would not quit the bounds of the establishment on any plea whatsoever, ill-health alone excepted.

Relatives were permitted to visit the girls whenever they chose, and on Sundays, the pupils received any lady of their acquaintance and male relations to whom the law prohibited them from marrying (this latter rule was constantly evaded however, with many dashing suitors proclaiming themselves to be “first cousin” to a pupil and gaining admittance to visit with them). Easter was the season for the sortie of finished pupils. Prior to the reception held at the home of her parents and friends, an apartment was prepared for her within the institute to that was filled with elegant furnishings and lavish gifts from friends, and if from a distinguished family, the Russian royals.

Austro-German court circles were tightly regulated, and none but the highest nobility could make headway (with the exception of wealthy Americans introduced by their ambassadors, and aristocrats of other nations). The imperial German court was usually held in either Berlin or in Potsdam, where the imperial family resided during its regular stay in town, which typically lasted from shortly after New Year’s until the middle of April or May. During these months the large court festivities took place at many fetes, consisting of several big court balls, at which attendance reached two to three thousand. They all open with the first “Defilir Cour,” or ceremonious reception, at which all persons entitled to presentation at court made their first obeisance to His Majesty.

Austro-German court circles were tightly regulated, and none but the highest nobility could make headway (with the exception of wealthy Americans introduced by their ambassadors, and aristocrats of other nations). The imperial German court was usually held in either Berlin or in Potsdam, where the imperial family resided during its regular stay in town, which typically lasted from shortly after New Year’s until the middle of April or May. During these months the large court festivities took place at many fetes, consisting of several big court balls, at which attendance reached two to three thousand. They all open with the first “Defilir Cour,” or ceremonious reception, at which all persons entitled to presentation at court made their first obeisance to His Majesty.

Those entitled to admittance included those who by reason of birth or official station, were members of the royal family, members of all other German dynasties present in Berlin, members of the aristocracy, all officers of the army and navy, all members of the Prussian and imperial cabinets, all persons who have been decorated, court and higher government officials, and members of the Prussian Diet, the Bundesrath, and the Reichstag. All considered eligible were called “courfahig.” The debutantes of the season were presented at the initial receptions by their mothers and wore gowns with deep decolletage and train of a certain length according to their rank.

In Vienna, the “Frauenheim,” which was given at the Sofiensaale, was the ball at which young girls made their debut, dressed entirely in white “similar to a bal blanc in France. It was usually patronized by an Archduke or Archduchess.” However, these unmarried princesses, countesses, duchesses and archduchesses had a special place in society. At every ball there was a room set aside for them called the “Comtessin Zimmer,” into which no married woman was allowed to penetrate. There the girls “gossiped with their partners between the dances, keeping a jealous and watchful eye on any erring sister who ventured to overstep the bounds of the most innocent flirtation.”

Overall, a young woman’s entrance into society marked a time of transition. There was no concept of “adolescence” at the time: a female was either a child or a woman, and her treatment and behavior was precisely dictated and delineated for the sole purpose of creating a perfect “wife.” This was a time where perhaps they were to meet gentlemen on equal footing for the first time, and indeed, a number of girls thrived within this mold. But it was an interesting time for these young women: once they put up their hair, they were expected to be “adults” and were immediately accorded the respect of an adult despite possibly having been horsing around in the nursery with younger siblings just the week before their debut!

Further Reading

1900s Lady by Kate Caffrey

Princess Daisy of Pless by Herself by Princess Daisy of Pless

Etiquette of American Society by Mrs. M.E.W. Sherwood

Society recollections in Paris and Vienna, 1879-1904 by George Greville Moore

France of To-day by Matilda Betham-Edwards

Russia of Yesterday and Tomorrow by Baroness Souiny

1913: A Beginning and an End by Virginia Cowles

The key thing about this post, for me, was that we/I tend to think of the English experience as the sole role model for debs everywhere. Partially I suppose because in British countries, when the deb curtsied to her city’s ball president, the ball president was representing the royals in absentia. But clearly the French, Austrians, Germans, Russians and others had their own value systems.

I must look for “1913: A Beginning and an End” by Virginia Cowles. Quite coincidentally my current post is called Glorious Days: Australia 1913. Thanks for the link

Hels

Art and Architecture, mainly

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com.au/2013/12/glorious-days-australia-1913-vida.html

It’s funny how the English experience is so dominant when many, if not all, of the recognized customs for the London season and for debutantes were established in the 18th and 19th centuries. The Cowles book is great–it touches on the eyar 1913 in London, Paris, Vienna, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and New York.

This was such an interesting post. All of these young women had such circumscribed lives. It seems so sad, now, in the light of the present age. Although at the time, I suppose they made a life out of it. But really, it seems such a limited life.

Thanks, Elizabeth. It is both sad and not sad: they were cossetted and restrained, but their lives were still more privileged than the majority of their countrywomen. Consuelo Vanderbilt’s life really reveals the dichotomy of being trapped in a gilded cage, yet the cage providing a platform for leadership.

Most interesting! Definitely extreme, but then came the opposite extreme … could we not somehow meet somewhere in the middle?

I think the middle was and is met by the middle-classes. More freedom and better chance of forging your own path.