In the mid-1890s, Daisy Warwick shocked society with her interest in socialist politics. At the time, British Socialism was a growing menace to the aristocracy and landed gentry, who viewed these working class rabble-rousers with disdain and anxiety. Daisy’s conversion to socialism came about when the Clarion, a weekly socialist newspaper, lambasted the lavish house-warming ball and party the naive Daisy felt sure was alleviating the poverty of the area. She traveled to Fleet Street as soon as possible to confront the editor of the newspaper, Robert Blatchford, only for Blatchford to rip apart everything she believed to be true. From then on, Daisy was determined to use her wealth and position to help the less fortunate. This of course caused much strain on her personal relationships, particularly with the Prince of Wales (though their romantic relationship quickly cooled, they remained great friends).

A few years after her conversion to socialism, Daisy grew just as interested in women’s rights, and was keenly interested in women’s education and employment. To that end, she decided to train educated women (that is, middle-class women) in horticulture and agriculture. She had already established a hostel for women pupils attending Reading College, and it seemed to her that “training at the Reading College in dairy work, market gardening, poultry-farming, bee-keeping, fruit growing, horticulture and grading, packing and marketing of produce, would appeal to many women of education, and would do something to meet the complaint that foreign competition was proving too much for our market gardeners.” She soon separated her hostel from Reading College and moved it to Studley Castle in Warwickshire in 1903, where it was named Studley Horticultural & Agricultural College for Women.

A contemporary description of the college:–

The park in which the College is situated is 340 acres in extent, and includes gardens and glass houses. The founder is responsible for the maintenance of the College, and Lady Warwick is assisted in its management by a committee of ladies and gentlemen. Instruction is given in horticulture, dairy-work, poultry keeping, bee keeping, fruit bottling and preserving, marketing, manual processes, and business methods, and students are prepared for the National Diploma in Dairying, the Certificates and Diplomas of the British Dairy Farmers’ Association, the College Certificate and Diploma in Dairying, and the examinations of the Royal Horticultural Society. The Certificate Courses are usually for one year, and the Diploma Courses for two years, with three years in the case of horticulture and bee keeping combined. The session is of forty weeks’ duration, and consists of three terms of about thirteen weeks each, beginning in September, January, and May. The number of students is between 30 and 40.

Fees.—Full training, with board and residence, £80 to £120 ($400 to $600), according to accommodation required, with extras for bee keeping, fruit bottling, etc. Non-resident students, £1 5s. a week or £13 6s. 8d. per term.

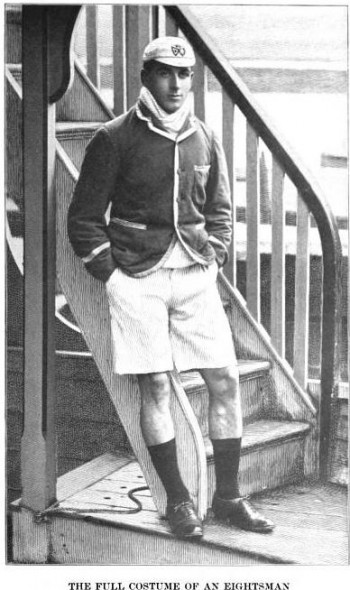

Nature Study Courses of two weeks for men and women are held in the summer, the women being accommodated at the College, and the men in farm lodgings. Fees, £5 5s ($25)., inclusive.

Staff.—Founder: Lady Warwick. Warden: Miss Mabel C. Faithfull. Horticulture: Mr. W. Iggulden, F.R.H.S.; Mr. W. Sarsons. Botany: Mr. W. B. Groves, M.A. (Cantab). Poultry: Mr. George A. Palmer. Dairy Farming and Agriculture—Dairy Instructress: Miss K. A. Baynes, N.D.D., B.D.F.A., Diploma. Book Keeping and Business Training: Mr. A. E. M. Long (Chartered Accountant). Apiculture: Mr. W. Herrod, F.E.S. Fruit Bottling and Jam Making: Miss Cran. Cooking Lessons: Miss Faithfull.

As it turns out, Daisy was right on the nose, for Edwardian England’s greatest garden designer was a woman–Gertrude Jekyll, whose partnership with Edwin Lutyens produced some of England’s finest gardens. Jekyll, however, studied at the South Kensington School of Art, but famous alumni of Studley College included Adela Pankhurst and Taki Handa a “student and instructor at Doshisha Women’s College of Liberal Arts, Japan, who studied at Studley from 1906-1907, and designed a garden at Cowden Estate in Muckhart, Scotland.” Studley College remained an all-female agricultural college until it closed in 1969 (the castle is now a Best Western hotel), long after Lady Warwick’s death, and it joined Swanley Horticultural College for Women in Kent, and Frances Wolseley’s School of Gardening for Ladies, as a tangible method for “surplus” Victorian and Edwardian women to control their destinies.

Further Reading:

History of Studley Castle

Photographs of Studley College, ca 1910-1930

“Horticultural Education in England, 1900-40: Middle-Class Women and Private Gardening Schools” Garden History

Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring, 2003) by Anne Meredith

Thanks for this wonderful and interesting post

@Shauni: You’re welcome!

South Kensington School of Art was world famous but I don’t think I have heard the name Studley Horticultural & Agricultural College for Women (1903) before. Bravo Daisy Warwick!

So the question is…. was training in dairy work, market gardening, poultry-farming, bee-keeping, fruit growing, horticulture and grading, packing and marketing of produce intended to be

1. truly vocational, with proper paid jobs in the open market?

2. serious but the women would only be tending their own kitchen garden after marriage? or

3. simply a useful time filler between school and marriage?

I ask you this because, by the outbreak of WW1 in 1914, we know a quarter of all British women were already in paid jobs. Yet these jobs were largely domestic, and to a less extent in textiles. What happened to Lady Warwick’s graduates?

Hels

http://melbourneblogger.blogspot.com.au/2012/03/ww1-from-national-heroines-to-national.html

@Hels: I would say a bit of all three. While women were not exactly educated to enter the commercial field (that is, production of honey or eggs or milk on the wholesale or retail markets), raising poultry or growing apples was a respectable way for middle class females to earn “pocket money”. As for the statistics, I don’t think these women would be counted since they were not officially in business–most likely sold their honey or eggs or fruit to neighbors or the village grocer, or perhaps to the manor house.

The college closed in the 1960s, but there was a trust set up for prospective students of agriculture. The website gives plenty of great information about the history of the college and trust. Here is an article from 2009 about the reunion of three graduates from the 1950s. And here is an article from an Australian newspaper from 1905 on the college. The college’s archives are available in the National Archives.

I came to EP quite by accident and arising from research I am doing on late-Victorian/early Edwardian participation of middle class women in higher education. I am seeking to focus first on the work of late Victorian education pioneers who established lodging houses or public hostels rather similar to Sudeley’s with the aim of developing and delivering formal HE education to women, unable to access the great universities eg at Oxford and Cambridge, because of barriers preventing their entry. This peripatetic form of education led on subsequenly to full participation at under-graduate level in the ancient and then the new civic universities emerging. Newnham and Homerton at cambridge started in this way. My question is whether you might be aware of other examples of peripatetic higher education for women in other places in England around 1880-1920. Mosr grateful for any response. Alan Lawson

@Alan Glad your search led to my site! I think you may find what you’re looking for in The Englishwoman’s Year book and Directory, which is available online. There is a substantial section on women’s education, as well as a list of colleges, schools, and coursework available to girls and women both outside and inside the traditional education system. The editor of this yearbook and directory began writing this in various forms from the late 1870s until the late 1890s, such as “A guide to all institutions existing for the benefit of women and children” (1878), “The Woman’s Gazette; or, News about Work” (1878), and “Work and leisure, the Englishwoman’s advertiser, reporter and gazette” (1883)–all of which will probably be helpful in tracing to rise of institutions and schools from the 1870s on. As far as I know, The Englishwoman’s Year book and Directory was published well into the 1900s, edited by Geraldine Edith Mitton, and they are probably available in British museums and libraries.