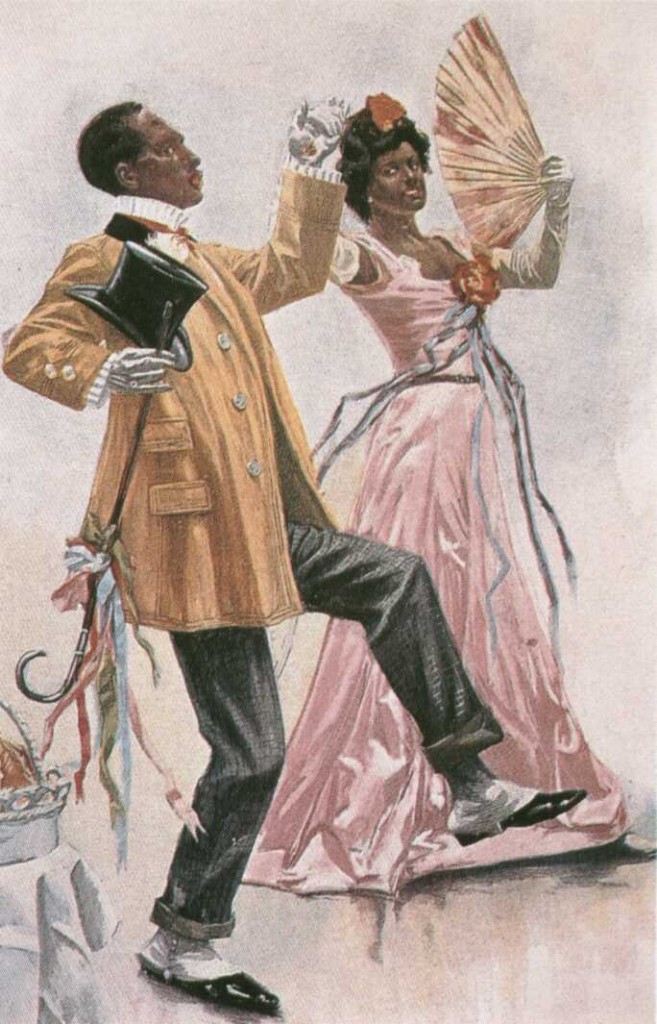

London society of 1913-1914 was tango mad. The dance made its way across the Channel from Paris, where it had become a vogue after its introduction by Argentinian dancers in 1910, and was adopted with even more alacrity than the cake-walk or the animal dances. As expected, the even greater physical contact of bodies and its “exotic” antecedents in the lower-class districts of Buenos Aires, precipitated even more denouncement from the moral leaders of the day and from royalty (the Kaiser banned the tango after learning his daughter-in-law, Kronprinzessin Cecilie was taking lessons).

Hostesses struggled with banning the dances from their ballrooms and from their debutante daughters, with an anonymous peeress declaring the Times: “I am one of the many matrons upon whom devolves the task of guiding a girl through the mazes of a London season, and I am face to face with a state of affairs in most, but not all, of the ballrooms calling for the immediate attention of those in like case. My grandmother has often told me of the shock she experienced on first beholding the polka, but I wonder what she would have said had she been asked to introduce a well-brought-up girl to the scandalous travesties of dancing which are, for the first time in my recollection, bringing more young men to parties than are needed…I…ask hostesses to let one know what houses to avoid by indicating in some way on their invitation cards whether the ‘Turkey Trot,’ the ‘Boston’ (the beginner of the evil,) and the ‘Tango’ will be permitted.”

These more conservative ladies could not stop the craze, particularly when many ultra-fashionable hostesses–including the Duchesses of Marlborough and Manchester, the Countess of Essex, Mrs. George Keppel, and Mrs. Hwfa Williams–gladly established themselves as the “chief tango hostesses” in high society.

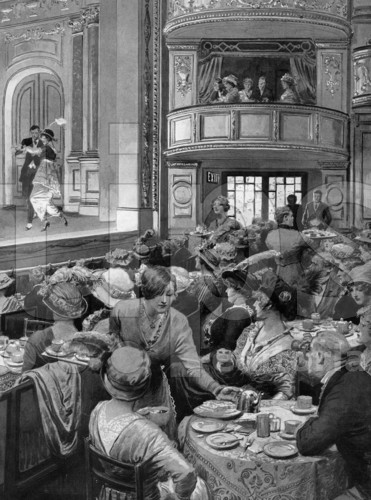

Soon, the tango moved out of ballrooms and into London’s top restaurants and hotels with the establishment of “tango teas.” These, according to Ethel Lucy Urlin in Dancing, Ancient and Modern, were “held more often than not in large hotels…A fixed charge is made for admission including tea, and a couple of young professionals engaged, who usually start the dances, a full programme of One-step and Two-steps being those most frequently desired, with a “Tango” or other dance of that nature interspersed to break the monotony.”

Princes’, the Hotel Cecil, the Savoy, and the Trocadero were the places for high society to watch and gossip as popular professional dancers like Maurice and Florence Walton, or Marquis and Gladys Clayton, displayed their nimble dance moves between the elegant tables. Traditional theatres like Queen’s Theatre in Shaftsbury Avenue and even the Opera House at Covent Garden cleared away their stalls to set up tables and chairs for tango teas, where the audience sipped tea and nibbled cucumber sandwiches and cake, which were included in the half-a-crown ticket. During these theater-based tango teas, the hired dancers tangoed, and their exhibition was followed by a dress parade of the latest modes.

The tango effectively killed the true hobble skirt of 1911-1912, and even the modification–a cleverly concealed slit–was declared an interference. Harem pants, introduced by Paul Poiret, were worn only by the most daring of women, so shrewd couturiers and dressmakers a bevy of more acceptable “tango” attire, like tango hats, tango stockings, tango waists, and tango shoes.

In 1914, the desire to tango, turkey trot, Boston, etc brought society to the nightclub (or supper club). The daring and raffish Lady Diana Manners had been sneaking away to nightclubs as early as 1912, most notably The Cave of the Golden Calf off Regent Street, but now that many restaurants were often closed after the later theatre hours, there was no place to dine or see and be seen after about 11 PM.

These nightclubs–the Lotus, the Four Hundred, Murray’s, among others–could be open as long as the proprietor pleased, and were also exclusive, being run along the lines of a traditional club, with dues and a capped membership.

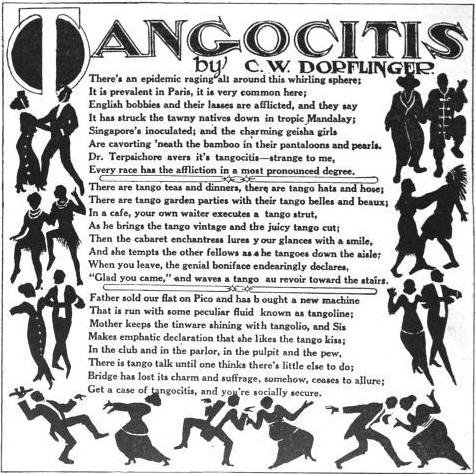

As was wont, new crazes and fads provided much humor to the wits of the day, and the following poem appeared in an American magazine (the tango had also swept American society at this time):

Further Reading

Edwardian Popular Music by Ronald Pearsall

The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances by Mark Knowles

Shopping, Seduction & Mr Selfridge by Lindy Woodhead

1913: An End and a Beginning by Virginia Cowles

This is so interesting! Thanks for sharing. : )

I think the idea of tango teas was a brilliant idea. Not in grand homes where the majority of ordinary middle class families could not get to, but in city hotels, large restaurants and traditional theatres.

Clearly people loved the music, movement, colour and social life, despite what their grandmothers thought! But isn’t that true in every generation?