Contrary to the calm and perfect photographs and portraits of stately Edwardian beauties, as well as the trim, pert figure of the Gibson or Gaiety Girl, loveliness took a lot of work. In my former post, The Chemistry of Beauty, we discussed the products Edwardian women used to beautify themselves, and it was surprising to learn that many of the products used by either ourselves, our mothers, or our grandmothers had roots in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But what is equally surprising are the beauty rituals and advice dished out to women in manuals published for the consumption of beauticians and the public. From manicures, to bunions and corns on the feet, to getting rid of gray hairs, and fighting wrinkles, a variety of modern-sounding treatments, exercises, and devices were created to help the distressed woman reach her full potential. Ironically, as also found in modern magazines and books, advice was given with the treacly sweet notion that a woman’s true beauty came from within.

Contrary to the calm and perfect photographs and portraits of stately Edwardian beauties, as well as the trim, pert figure of the Gibson or Gaiety Girl, loveliness took a lot of work. In my former post, The Chemistry of Beauty, we discussed the products Edwardian women used to beautify themselves, and it was surprising to learn that many of the products used by either ourselves, our mothers, or our grandmothers had roots in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But what is equally surprising are the beauty rituals and advice dished out to women in manuals published for the consumption of beauticians and the public. From manicures, to bunions and corns on the feet, to getting rid of gray hairs, and fighting wrinkles, a variety of modern-sounding treatments, exercises, and devices were created to help the distressed woman reach her full potential. Ironically, as also found in modern magazines and books, advice was given with the treacly sweet notion that a woman’s true beauty came from within.

The Hand

The Hand

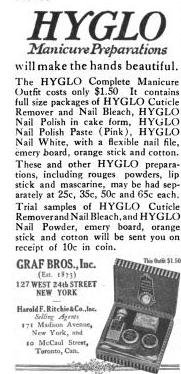

Manicuring had formerly been considered a part of the doctor’s profession, but by the turn of the century, it became a separate practice in its own right, and a recommended occupation for working women. Because of the sudden demand for manicurists, it was a very lucrative profession, and its short hours, the ability to have a flexible schedule, and its all-around glamorous aura, young women acquired manicurist licenses in droves. Many times a manicurist was attached to a barber shop, and oddly enough, the first consumers for this new service were men! The work was simple, consisting of the trimming and shaping of the nails, trimming the cuticle, and when necessary, performing slight operations in shaping the nail or doing away with hang nails, and also removing stains and polishing. A complete set of tools for the expert manicurist included a file, scissors, cuticle knife, buffer, polisher, orange sticks, finger bowl, nail brush, and emery boards. Other items necessary for a manicurist were Castile Soap, Borax, Nail Bleach, Nail Powder or Polish, Nail Cream, Cold Cream, Styptic Pencil, and Tincture of Benzoin, which was used as an antiseptic.

Nail polish existed in various forms since before A.D., and 19th century cookbooks contained directions for making nail paint, the stigma against any form of cosmetic was too strong, and most women merely polished their nails with tinted powders and creams into their nails, then buffing them shiny. Nail polish could also be mixed by manicurists. One mixture was composed of Oxide of Tin, Carmine, Oil of Lavender, and Oil of Bergamot. Tips were, however, whitened with items such as Cutex Nail White, and polished with Cutex Nail Cake. Care for the nails included massaging cocoa butter, Vaseline, or olive oil on them for shine and health. One of the famous polishing products sold was Graf’s Hyglo nail polish paste. Women used this clear, glossy varnish to paint their nails with camel-hair brushes. Colored nail polish didn’t arrive on the scene until 1920, inspired by automobile paint, as until then, cars were typically black or maroon in color. But it wasn’t until the 1940s that the entire nail was painted–it was fashionable in the 1920s and 1930s to leave bare the tips and half-moon on the nail-bed.

Nail polish existed in various forms since before A.D., and 19th century cookbooks contained directions for making nail paint, the stigma against any form of cosmetic was too strong, and most women merely polished their nails with tinted powders and creams into their nails, then buffing them shiny. Nail polish could also be mixed by manicurists. One mixture was composed of Oxide of Tin, Carmine, Oil of Lavender, and Oil of Bergamot. Tips were, however, whitened with items such as Cutex Nail White, and polished with Cutex Nail Cake. Care for the nails included massaging cocoa butter, Vaseline, or olive oil on them for shine and health. One of the famous polishing products sold was Graf’s Hyglo nail polish paste. Women used this clear, glossy varnish to paint their nails with camel-hair brushes. Colored nail polish didn’t arrive on the scene until 1920, inspired by automobile paint, as until then, cars were typically black or maroon in color. But it wasn’t until the 1940s that the entire nail was painted–it was fashionable in the 1920s and 1930s to leave bare the tips and half-moon on the nail-bed.

The Foot

Though heels were never as high as today’s stilettos, women of the Edwardian period did suffer from corns, bunions, and other ailments of the foot. Chiropody was also a lucrative, though arduous occupation that arose in the Edwardian era. Chiropody also derived from the medical field, and licensed chiropodists were trained not only in massage, but in the anatomy of the foot. The tools a proper chiropodist had on hand were hones to sharpen instruments, nail nippers to cut heavy nails, a chisel knife for fine work (not on calluses or nails), tweezers, shears, a scapula, an operating knife for work on corns, bunions, ingrown toe ails, and calluses.

A chiropody parlor was furnished with well-lit booths or small apartments, where an easy chair was provided for each customer and a low stool for the chiropodist. Feet were soaked in a bath, massaged, and the nails trimmed–recommended once every two weeks–and calluses rubbed with a pumice stone. For bunions and corns, excessive care was taken in their removal. Careful advice was given to clients about the dangers of abusing one’s feet, such as:

- Sore feet hasten the advent of old age

- Diseased feet cause premature grayness

- Every long-neglected corn may be the seen of a dozen gray hairs

- The story of injured feet writes itself in wrinkles on the face

- High heels cause week knees

- Weak knees pave the way to nervous breakdown

- Pressure of pain in any part of the body, long continued, seriously marks the expression of the face, disturbs and sometimes ruins the disposition, and may upset the brain at last

The Face

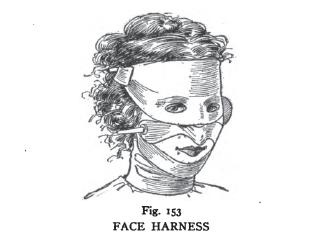

One beauty manual of this time considered beauty a God given gift and its preservation “a solemn duty.” To preserve this beauty, women visited masseuses as often as they did manicurists and chiropodists, and the facial massage became as necessary to women as to men who wished to retain their youthful looks. Masseuses believed that hard, firm strokes caused the parts to waste by destroying fatty cells, while easy, gentle pressure built up the tiny cells and caused development by increasing the circulation and the blood supply to the wasted parts. Hand massages were considered too slow, and a number of machines for vibratory massage were developed, the most recommended being Automatic Massage or Hydro-Vacu.

One beauty manual of this time considered beauty a God given gift and its preservation “a solemn duty.” To preserve this beauty, women visited masseuses as often as they did manicurists and chiropodists, and the facial massage became as necessary to women as to men who wished to retain their youthful looks. Masseuses believed that hard, firm strokes caused the parts to waste by destroying fatty cells, while easy, gentle pressure built up the tiny cells and caused development by increasing the circulation and the blood supply to the wasted parts. Hand massages were considered too slow, and a number of machines for vibratory massage were developed, the most recommended being Automatic Massage or Hydro-Vacu.

The client sat in a comfortable chair, the hair was pinned back, the collar removed and a towel was tucked around the neck to protect the clothing. Then a large apron was placed over the client’s body. The masseuse then rubbed a cold cream over the face, which also acted as a bleach to remove impurities from the skin’s surface. The “Automatic Massage Bag” was filled with very hot water if the client’s skin was inclined to be oily or prone to blackheads, or lukewarm, with a teaspoon of powdered borasic acid, if normal to dry. The bag was hung about six feet from the floor and the client’s face was wiped clean of the cream. The “Depurator” was placed on the face, the clasp opened, and moved slowly upward on the mouth line, to the nose, across the cheek, up to the temple, and down across the lines that formed beneath the eyes. Also applied to the face during this process was the “Tissue Food,” and if the client wanted plump cheeks, the “Depurator” was worked in circles where the plumpness was desired. If age lines or blemishes remained, hand massage was the next step, and unless the client wanted a reduction in flesh, the massage was light and with fingertips only.

The client sat in a comfortable chair, the hair was pinned back, the collar removed and a towel was tucked around the neck to protect the clothing. Then a large apron was placed over the client’s body. The masseuse then rubbed a cold cream over the face, which also acted as a bleach to remove impurities from the skin’s surface. The “Automatic Massage Bag” was filled with very hot water if the client’s skin was inclined to be oily or prone to blackheads, or lukewarm, with a teaspoon of powdered borasic acid, if normal to dry. The bag was hung about six feet from the floor and the client’s face was wiped clean of the cream. The “Depurator” was placed on the face, the clasp opened, and moved slowly upward on the mouth line, to the nose, across the cheek, up to the temple, and down across the lines that formed beneath the eyes. Also applied to the face during this process was the “Tissue Food,” and if the client wanted plump cheeks, the “Depurator” was worked in circles where the plumpness was desired. If age lines or blemishes remained, hand massage was the next step, and unless the client wanted a reduction in flesh, the massage was light and with fingertips only.

Some ingredients for making cold cream were Lanolin, Almond Oil, Cocoa Butter, Benzoin, Coconut Oil, White Wax, Spermaceti, Petrolatum, Glycerine, and Witch Hazel. Wrinkles were thought to be the result of an internal disorder, and a lack of oil in the system, which led to starved tissues beneath the skin. Those with wrinkles were advised to drink plenty of rich milk and cream, take olive oil on salads, and equal parts grape juice night and morning, to eat vegetables and fruits and drink quantities of water each day, as well as keeping the bowels well regulated. Other ailments for which beauticians treated were freckles, sun tans, sunburns, liver spots, oily skin, blackheads, and acne. Another process for ridding the body of unwanted blemishes was electrolysis, which removed superfluous hair, warts, moles, varicose veins, birthmarks, and scars with a electric needle.

The Body

Despite hiding the figure beneath layers of petticoats, underclothing, and corsets, flesh reduction and good health were a common concern with women of this period. Though there were a series of dieting fads, women and men still searched for exercises and regimens to force their bodies into the svelte–or muscular–silhouettes of their youth. A beauty manual found three things essential for success in weight loss: diet, exercise, and perspiration. Turkish baths taken once a week were advised, regulated bowels, and drinking copious amounts of vichy or kissengen water. Sugared drinks and alcohol, as well as milk, cream, cocoa, chocolate, butter, oil, starchy foods, white bread, sweets, pork, fat meats, and hot cakes were to be avoided. If possible, rubber undergarments made of medicated rubber tissue, which caused profuse perspiration and melted the fatty cells without violent exercise, were to be worn.

There were a number of dieting systems promoted by health gurus:

BANTING’S SYSTEM: Created by William Banting, who advised the removal of all saccharine, starchy, and fatty foods from the diet, and the substitution for these of meat or fish and fruit in moderate quantity at each meal, together with the reduction of the amount of liquids cosumed, and the daily use of an antacid.

SCHWENINGER’S SYSTEM: Dr. Schweninger of Munich based his method on a careful analysis of each case and each patient’s previous ailments. He deduced that the intake of fat-forming food must be reduced, while the expenditure of energy must be increased. Recommended foods were lean fish and lean beef, mutton, olives, onions, stale bread, poached eggs, skimmed milk, vinegar, mineral water, etc, while avoided or sparingly eaten foods were fatty and greasy foods, thick soups, white bread, sugar, candy, pies, macaroni, salmon, made dishes, pork, etc.

Exercises recommended were rolling around the room in as little clothing as possible for ten to two hundred turns, depending on experience; walking; massage–including the Zander Method (a vigorous tapping with electrically driven leather-covered hammers)–hand massage of double chins; push-ups; leg lifts; and sit-ups.

On the other side, some men and women desired to add flesh to their thin and scrawny forms. They were advised to eat fatty foods, but to consume them often, rather than stuffing one’s self at mealtimes. Another major concern for women was the development of the bust, and exercises and creams were developed to aid in helping women achieve what nature felt fit to withhold from them.

Hair

By the 1900s, a growing segment of women broke away from the former practice of washing the sporadically, rarely brushing, and otherwise negligence of their locks to devote actual care to their hair. Now shampoos were developed to treat alopecia and dandruff, as well as special mixtures for brunettes and blondes, and those with oily hair, dry scalp, or curly hair. Hair coloring was another practice, though women winked at one another over the directions given for coloring only gray hair. Titian or copper-colored hair was obtained by a henna paste, which was spread over the hair with a small tooth brush. The hair was then wrapped in hot towels for at least fifteen minutes, or longer, should one wish for a deeper hue. Hair was bleached with dioxogen and ammonia, and it was darkened with sulphate of iron. The prevention of gray hair, which was said to be caused by dryness, was from a mixture of oil, rum, glycerine, and oil of bergamot. After shampooing, brilliantine, which was a rich glossy product, was applied, to give hair a nice sheen.

By the 1900s, a growing segment of women broke away from the former practice of washing the sporadically, rarely brushing, and otherwise negligence of their locks to devote actual care to their hair. Now shampoos were developed to treat alopecia and dandruff, as well as special mixtures for brunettes and blondes, and those with oily hair, dry scalp, or curly hair. Hair coloring was another practice, though women winked at one another over the directions given for coloring only gray hair. Titian or copper-colored hair was obtained by a henna paste, which was spread over the hair with a small tooth brush. The hair was then wrapped in hot towels for at least fifteen minutes, or longer, should one wish for a deeper hue. Hair was bleached with dioxogen and ammonia, and it was darkened with sulphate of iron. The prevention of gray hair, which was said to be caused by dryness, was from a mixture of oil, rum, glycerine, and oil of bergamot. After shampooing, brilliantine, which was a rich glossy product, was applied, to give hair a nice sheen.

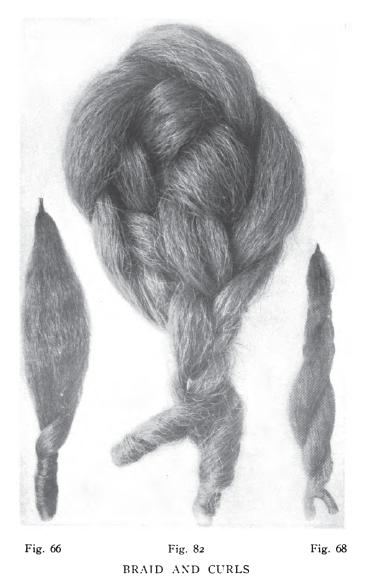

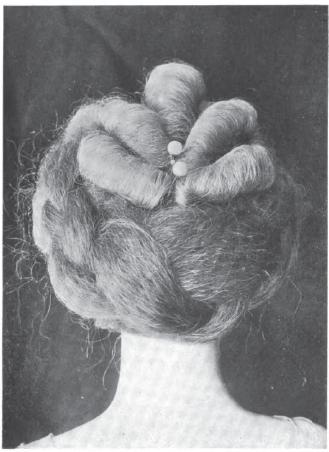

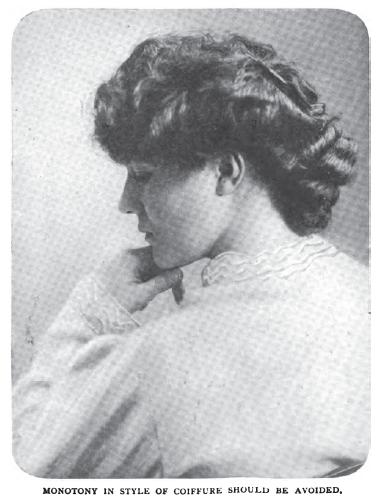

The dressing of hair was not a simple task. However, the styles favored by Edwardian women were aided with the help of hair switches, false braids, and “rats” collected from their hairbrushes.

Further Reading:

The Barbers, Hairdressers, and Manicurerers Manual by A. B. Moler

Beauty Culture by William A. Woodbury

Beauty Culture At Home by Pauline Furlong

Beauty’s Aids, or How to be Beautiful by the Countess of C—-

Absolutely fascinating post! Wow. That facial massage machine sounds like torture, though!

Doesn’t it? But I’m not entirely convinced that that type of massage fully disappeared. I neglected to add a section on plastic surgery! Now that was something both fascinating and frightful to read about!

lol! Every response to this post has been one of horror.

They reused old hair in their brushes? Eugh.

*g* They sure did!

That sounds absolutely exhausting! I don’t fancy the weight-loss ideas much – corsets, electric hammers, rolling round the room – not for me!

Doesn’t it? I had a good laugh while I read those beauty books–it’s enough for me to go the gym for an hour at least three times a week–I can’t imagine doing all of that every day!

Fascinating read. You are right to note that colored nail polish only took off well after World War One. The same goes for most colored cosmetics. I think it is very interesting that the term “generation gap” was only first used in America in 1925 to describe the disagreement between mothers and daughters regarding wearing colored lipstick.

What a fascinating post! The hairstyles alone were astonishing — the amount of time it must have took to do your hair is mind-boggling. I have always been envious of the full, pouffy styles they wore. You might be interested in my blog, devoted to the 1890’s: http://www.thefindesiecle.com

You have such a lovely blog here — what agreat resource!

TAra