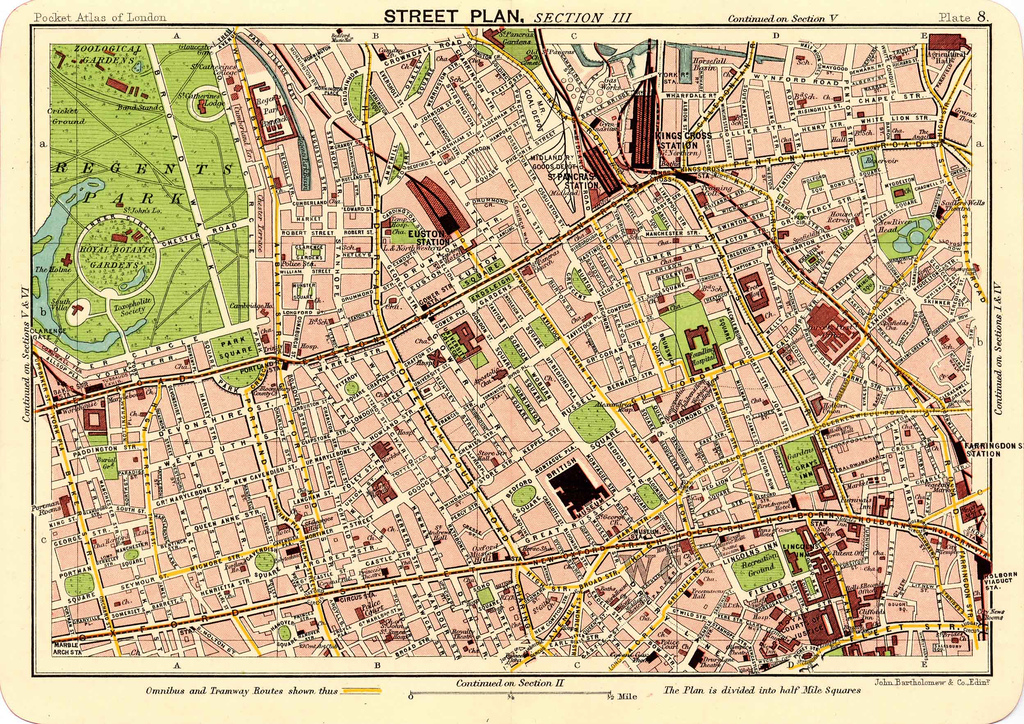

Long before Virginia Woolf and her “Bloomsbury Group” became synonymous with the now quaint London neighborhood, the area was a “grimy, sordid, squalid region” where “no nice people lived.” Its boundaries roughly defined by Tottenham Court Road to the west, Euston Road to the north, Gray’s Inn Road to the east, and either High Holborn or the thoroughfare formed by New Oxford Street, Bloomsbury Way and Theobald’s Road to the south, it was ,generally, the bridge between the glittering, aristocratic West End, the sooty City and the poorer districts of Holborn in the south, St Pancras in the north-east and Clerkenwell in the south-east. Nonetheless, the district was known for its abundance of gardened squares and numerous hospitals and academic institutions–if not its most famous tenant, the British Museum.

Long before Virginia Woolf and her “Bloomsbury Group” became synonymous with the now quaint London neighborhood, the area was a “grimy, sordid, squalid region” where “no nice people lived.” Its boundaries roughly defined by Tottenham Court Road to the west, Euston Road to the north, Gray’s Inn Road to the east, and either High Holborn or the thoroughfare formed by New Oxford Street, Bloomsbury Way and Theobald’s Road to the south, it was ,generally, the bridge between the glittering, aristocratic West End, the sooty City and the poorer districts of Holborn in the south, St Pancras in the north-east and Clerkenwell in the south-east. Nonetheless, the district was known for its abundance of gardened squares and numerous hospitals and academic institutions–if not its most famous tenant, the British Museum.

Bloomsbury was a mixture of shabby genteel and intellectual atmospheres. The old, solidly built Georgian houses had a dignity of their own, and many were converted into shabby, but clean, boarding or temperance houses run by respectable ladies. Some of the streets had come down in the world; in their decay, they retained “a mournful look of having known better days; a look that even their tenement rooms their broken windows, half-stuffed with paper, and their shock-headed dirty inmates [could not] altogether abolish or destroy.” One thing the neighborhood could not escape was the pervading smell of fried fish, which gave rise to jokes that “Bloomsburians live[d] mainly on a dish called ‘Smoked ‘Addick‘.”

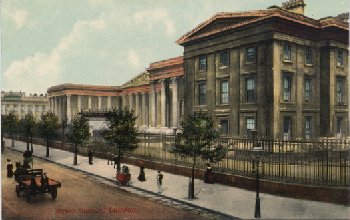

The existence of the British Museum and various professional institutions brought a naughty “Bohemian” atmosphere to the district. The population of Bloomsbury largely composed of those that eddied round and round the Museum: the students from overseas–both foreign and from the British colonies–, the continental scholar writing his magnum or other opus, and generally all who filled the boarding houses of which Bloomsbury almost entirely consisted. London University in Gower Street was not far away and students of both Museum and University formed a continuous population, a sort of “Latin Quarter” as different from the Parisian one as could well be imagined.

The existence of the British Museum and various professional institutions brought a naughty “Bohemian” atmosphere to the district. The population of Bloomsbury largely composed of those that eddied round and round the Museum: the students from overseas–both foreign and from the British colonies–, the continental scholar writing his magnum or other opus, and generally all who filled the boarding houses of which Bloomsbury almost entirely consisted. London University in Gower Street was not far away and students of both Museum and University formed a continuous population, a sort of “Latin Quarter” as different from the Parisian one as could well be imagined.

The squares themselves were found cheek-by-jowl with one another’s differing attitudes. But these were not always boarding houses. Literary and other associations cluster thickly about them. The high ground on which Bloomsbury is built (for it is a gradual ascent all the way from the river to Russell Square) rendered it–its fogs and soot notwithstanding and despite the old tradition that the victims of the plague were mainly buried here–far more bracing than the more fashionable West End. It had certainly its quota of fogs or, “London particulars” as Sam Weller called them, but so had other parts of London.

Queen Square, laid out in the reign of Queen Anne and adorned with a statue whose figure is still questioned today (a toss-up between Queen Anne or George III’s consort, Queen Charlotte), is a curiously shaped square. Though enclosed, no houses were built at the northern end.This arrangement was made for the sake of the fine view of the hills of Highgate and Hampstead that the square then commanded. In and about Great Ormond Street and Queen Square are many hospitals, large airy and splendidly managed institutions such for instance as the well known Great Ormond Street Hospital for Sick Children, the National Hospital for Epilepsy and Paralysis under the great Dr Ferrier, and the tall newly built Alexandra Hospital for children. In Powis Place, close to Queen Square, Lord Macaulay lived in early manhood with his family. The house is now joined to the Homoeopathic Hospital. In Great Ormond Street also on the northern side is the Working Men’s College the history of which is so deeply associated with Ruskin, Rossetti, Madox Brown and their friends.

Russell Square, a large and orderly square whose gardens were originally designed by Humphry Repton, was named after the earls and dukes of Bedford, who developed the family’s landholdings in the 17th and 18th centuries. This square was created when new streets were laid out by the duke on the site of the gardens of his former London seat, Bedford House. The surrounding streets contained large terraced houses aimed mainly at upper middle class families and the street lamps all carried the Bedford Arms. At No 65 lived the celebrated painter, Thomas Lawrence, where he received the famous and eminent sitters who made his name famous. At No 66 was a curious relic, a silent, palatial, empty house, from Bloomsbury’s fashionable days.

Bedford Square, built between 1775 and 1783, also targeted upper middle class families. The large, spacious terraced Georgian-style houses were called home by many well-known personages. No 48 housed Elizabeth Jesser Reid, anti-slavery activist and founder of Bedford College for Women; No 6 Lord Eldon, England’s longest-reigning and most popular Lord Chancellor; Margot Asquith, Prime Minister H.H. Asquith’s outspoken wife lived at No 44; and Sir Johnston Forbes-Robertson, one of the theatre’s finest Hamlet’s, resided at No 22.

For many years after its construction, Bloomsbury Square and its premiere home, Bedford House, were sights of London. About 1760, the square was so countrified that the Duchess of Bedford used to send out cards to her guests, inviting them to Bedford House to “take tea and walk in the fields.” By the Regency era, the square, shorn of Bedford House, had ceased to be fashionable, and as the century progressed, the square was mainly occupied by middle-class professionals. By the Edwardian era, resident had been ousted by offices of professionals and solicitors.

Gordon Square was developed by Thomas Cubitt in the 1820s, as one of a pair with Tavistock Square, which is a block away and has the same dimensions. The economist John Maynard Keynes lived at 46 Gordon Square, and the same house was used by the Bloomsbury Group before Keynes moved in when Vanessa Bell lived here. Fellow Bloomsburyite, Lytton Strachey, lived at No. 51.

At No 32, Brunswick Square, lived Punch artist John Leech, whose illness was aggravated by the organ grinders and minstrel singers who gravitated to the area from nearby Hatton Garden. Great Coram Street, west of this square, was the home (at No 13) of Thackeray during the early period of his marriage, and where he wrote his Paris Sketch Book. “Highly respectable, but not at all fashionable,” was the cruel sentence pronounced for this square and its neighbor opposite, across the grounds of the Foundling Hospital, Mecklenburgh Square.

Founded in 1739 and built in Bloomsbury in the 1740s, Captain Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital was a children’s home established for the education and maintenance of exposed and deserted young children. Its playing-grounds looked out onto Lamb’s Conduit Street where passers-by could glimpse the children in their uniforms–boys in their brown and red, and girls in brown frocks, white caps, tuckers and aprons–each sex playing on opposing sides. Lamb’s Conduit Street itself was a place of amusement; filled with curio shops, Hindo idols, yellow dragons and the like, glaring from behind grimy shop windows. Secondhand bookstores could also be found in Bloomsbury, with rare gems and old classics piled high in dingy corners.

Bloomsbury’s smaller squares include Woburn Square, Torrington Square (both made from pieces of the Duke of Bedford’s demolished London house, Red Lion Square, Regent Square and Argyle Square. Mrs Siddons, Lord Eldon, and Millais at No 87, once lived in Gower Street, and Woburn Square holds in Christ Church a memorial of Burne Jones design to Christina Rossetti who, however; lived in Torrington Square No 80. Red Lion Square, laid out in 1698 taking its name from the Red Lion Inn, is intimately connected with nineteenth century art and literature, for William Morris practiced his various crafts at No 9, and at No 17 once lived Burne Jones and Rossetti. According to some sources the body of Oliver Cromwell and two other regicides was placed in a pit on the site of the Square. In Theobald’s Road near by, at No 28 Benjamin Disraeli was born in 1804. By Lamb’s Conduit you come to Great Ormond Street, once a home of Macaulay at No 50, as also of Chancellor Thurlow at No 44. In Hunter Street, leading from Brunswick Square, at No 54 John Ruskin was born, and at 48 Doughty Street, Mecklenburg Square was once a home of Dickens, as No 14 was of Sydney Smith.

Adjoining organ-grinders and minstrel-singers, were “pavement artists”, who camped out in the squares and streets of the district with pastels, paints and canvas, to render the scenery or passers-by who consented to being sketched at the rate of a few shillings. Residents and visitors to the area could find a number of amusements to engage in and catch their eye, in particularly the British Museum. The stranger having satisfied the Cerberus at the wicket gate that he or she is over twenty-one, a warm atmosphere, a comfortable seat, and a luxurious leather desk awaited the jaded wayfarer with further polite attendants in the innermost circle to assist, if necessary his researches; and should he be hungry, a further possibility of a cheap lunch of sausage and mashed potatoes sandwiched between slices of crusty bread, could be found in the refreshment rooms. The British Museum gradually absorbed all the houses near it, and in 1906, plans were made to amalgamate the eastern side of Bedford Square and part of the western side of Russell Square.

Posterity has coupled The Bloomsbury Group with this district of London. An English collectivity of loving friends and relatives who lived in or near London during the first half of the twentieth century, their work deeply influenced literature, aesthetics, criticism, and economics as well as modern attitudes towards feminism, pacifism, and sexuality. Coming mostly from upper middle-class professional families, several members of the Group (E. M. Forster, Virginia Woolf and Vanessa Bell) had small independent incomes. Others such as Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, the MacCarthys, Duncan Grant, and Roger Fry needed to work for their livings. Only Clive Bell could be called wealthy. All the male members of the early Bloomsbury Group except Duncan Grant were educated at the Cambridge colleges of Trinity College or King’s College. At Trinity in 1899 Lytton Strachey, Leonard Woolf, Saxon Sydney-Turner and Clive Bell became good friends with Thoby Stephen, who introduced them to his sisters Vanessa and Virginia in London, and in this way the Bloomsbury Group came into being.

The district has had its ups and downs: from ultra-fashionable residence in the 17th and 18th centuries to professional, medical and slightly nefarious, it nonetheless retained its draw for the Bohemian aspects of society–the artists, authors and theatrical groups–who have granted us, and generations to come, the gifts of aesthetic and literary masterpieces.

Further Reading:

Virginia Woolf’s London: A Guide to Bloomsbury and Beyond by Jean Moorcroft Wilson

What an awesome new look! I adore it. Thanks for the linkage and have a happy New Year!

What a lovely site to stumble upon during my family tree searching. My grt grt grandparents lived in Hunter Street, Bloomsbury between 1891 and 1901. This site gives me some insight into how they lived. My gr grt grandfather was a Solicitor and I know that they lived a rather rich life.

Kerry (in Australia)

Interesting to read about Thoms Cubitt’s work for the Russells in Bloomsbury.

At the same time he was doing the same up the road in Pimlico. The works his family firm did in the 1820s and 30s were on a staggering scale. It’s hard to imagine private industry doing the same today on a speculative basis – I suppose Canary Wharf is the closest in modern times, but that had massive stock market money behind it.

Thoroughly enjoyed this – thank you.