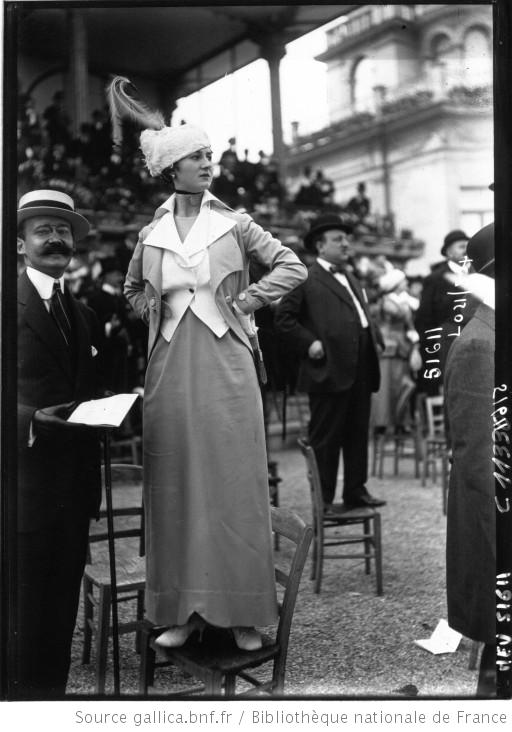

Ladies’ fashions had pretty much settled by the Edwardian era. The days when Charles Worth would wreak sensation and havoc upon the lives of his female clients had passed, and for the most part, the silhouettes of the 1880s, 1890s and early 1900s flowed neatly with one another; only minor bumps like the brief fashion for leg-o-mutton sleeves, bloomers for cycling and trousers beneath riding skirts for the slow, but growing number of women who rode astride, caused consternation. But a schism formed around 1907, when the elegant, oh-so-feminine and decorous colors and shapes of the turn of the century shifted to a streamlined, athletic look. Women were straining at their tethers—suffragettes, more positions opened for them, exciting artistic developments, and a greater voice in their roles in society—and it was a given that clothing mirrored this movement. The mood also carried a whiff of youth, a whiff that while not fully blossomed until the 1920s, had its origins in the pre-War period and heralded one of the largest changes in society since the Industrial Revolution.

Into the fray came Mariano Fortuny and his Delphos gown of 1907, that “creation which clung to the form in long crinkled lines and shimmered like the skin of a snake”. Born in Granada, the ancient Moorish capital of Spain to a family of Spanish artists, Mariano—named after his painter father—was to be forever influenced by the faded, slightly oriental opulence of the land of his birth. His father died when Mariano was three, and his newly widowed mother took her young son to Paris, where she hosted a salon comprised of her husband’s associates and other artists who flocked to France’s capital in the closing decades of the 19th century. Mariano was encouraged by his mother to take up painting, and he showed considerable skill at an early age. However, his mother moved yet again, but this time to Venice. Ten years later, Mariano moved to the Palazzo Pesaro Orfei, a magnificent 13th century palace whose large, open spaces were an idea work place where he could give full rein to his talents. It eventually became the Palazzo Fortuny, “the house of the magician.”

Fortuny produced his legendary textiles in the early 1900s, and they were immediately touted as incredibly durable, with an almost mystical appearance, and became widely popular due to their inimitable beauty and versatility. He found inspiration in 15th century Florence, 17th century Venice, Persia, Asia, South America, Egypt, China and Greece, and he had a particular interest in the Arabic Empire during the era of its greatest expansion, when it extended from Morocco to India, passing through Persia and the Near East. Another source of inspiration was the German composer Wagner. Fortuny utilized the images garnered from the legends upon which Wagner’s operas were based for his paintings and engravings, and his own formulations of dyes and pigments based on the ancient techniques of the masters gave his materials the appearance of authentic antiquity.

Further inspired by Wagner, Fortuny went on to do much work in the theater, specifically related to lighting and set design.  This theater work led him, during the course of research, to his first serious contact with the art of costume. He began as a designer of costumes for several theatrical productions, but his first purely fashion garment was the Knossos scarf. The scarf, made of silk and rectangular in shape, was printed with geometric, asymmetrical patterns and motifs inspired by Cycladic art. They could be used in a number of ways, allowing great freedom of expression and movement to the human body. It was from these simple scarves, which showed him how to fuse form and fabric, that Fortuny developed his entire production of dresses.

This theater work led him, during the course of research, to his first serious contact with the art of costume. He began as a designer of costumes for several theatrical productions, but his first purely fashion garment was the Knossos scarf. The scarf, made of silk and rectangular in shape, was printed with geometric, asymmetrical patterns and motifs inspired by Cycladic art. They could be used in a number of ways, allowing great freedom of expression and movement to the human body. It was from these simple scarves, which showed him how to fuse form and fabric, that Fortuny developed his entire production of dresses.

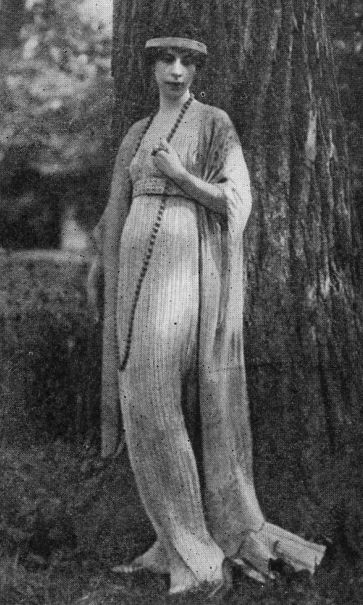

For their full effect, Knossos scarves needed to be worn as embellishments to a particular type of dress. This dress appeared around 1907 and was called the Delphos robe. Working closely with his wife, Henriette, their work combined the ideals of the Aesthetic Movement and Modernism. Henriette assisted Fortuny in the manufacture of his unusual dyes and pigments and also made up the garments. They devised unique printing and stenciling techniques for the exquisite silks and velvets. Delphos gowns were dyed individually in a wide range of unusual colors, and the delicate silk was processed on porcelain rollers to create fine, uneven pleats, one of his many innovations. The early Delphos gowns had short bat-wing sleeves, laced along their tops. Because of the elastic quality of the pleating, Fortuny weighted his dresses by sewing cords strung with hand-blown Venetian glass beads down the sides. To keep their pleats, the dresses were twisted like skeins of yarn and packed into a small cream-colored box.

The dress was a revolution for the tightly corseted women of 1907.

The dress was a revolution for the tightly corseted women of 1907.

The tenets of both the Modern and the Aesthetic Movements aimed for the creation of a style freed from the restraints of convention. Followers of the Aesthetic Movement looked nostalgically to Classical Greek and medieval dress for their models. Dress, they felt, should be artistic, hygienic and functional, and not subject to the whims of fashion, which created a kind of clothing that imprisoned the body like a rigid shell. Though the soft, gentle colors favored by the Aesthetes predominated in Fortuny’s designs, in his hands they gained a special richness and brilliance. The silk was dipped several times, each application enriching the color which, due to the transparency of the dye, possessed an ambiguous and living quality that made it change according to light and movement. He never used the same design or identical color combination in any two pieces of fabric.

According to Emily Burbank’s Woman As Decoration,

“These Fortuny tea gowns slip over the head with no opening but the neck, with its silk shirring cord by means of which it can be made high or low, at will; they come in black gold and the tones of old Venetian dyes. One could use a dozen of them and be a picture each time, in any setting, though for the epicure they are at their best when chosen with relation to a special background. The black Fortunys are extraordinarily chic and look well when worn with long Oriental earrings and neck chains of links or beads which reach at least one strand of them half way to the knees.”

Parisian society welcomed Fortuny’s fashions with open arms. In Remembrance of Things Past, Proust’s fictionalized peek into the intimate society of France’s gratin, or, upper crust, there are at least sixteen references to Fortuny or to his dresses.

“Of all the indoor and outdoor gowns that Mme de Guermantes wore, those which seemed most to respond to a definite intention, to be endowed with a special significance, were the garments made by Fortuny y Madrazo from old Venetian models. Is it their historical character, is it rather the fact that each one of them is unique that gives them so special a significance that the pose of the woman who is wearing one while she waits for you to appear or while she talks to you assumes an exceptional importance…?”

A particular velvet is described as:

“being of an intense blue which, as my gaze extended over it, was changed into malleable gold, by those same transmutations which, before the advancing gondolas, change into flaming metal the azure of the Grand Canal.”

All Delphos gowns were produced in his studio. Each was made individually by hand, as were all the materials that went into them: the pleated and printed silk, the velvets, the cords used to gather them or unite the different parts, the linings which were of satin , silk, wool, the belts, the labels. Everything was made on the premises (only the tiny Venetian glass beads threaded onto silk cord at the neck and armholes were made elsewhere), including accessories. Since the dresses had no pockets and their wearers needed bags, Fortuny obliged his clients and constructed handbags from his own multicolored velvet in very simple designs.

All Delphos gowns were produced in his studio. Each was made individually by hand, as were all the materials that went into them: the pleated and printed silk, the velvets, the cords used to gather them or unite the different parts, the linings which were of satin , silk, wool, the belts, the labels. Everything was made on the premises (only the tiny Venetian glass beads threaded onto silk cord at the neck and armholes were made elsewhere), including accessories. Since the dresses had no pockets and their wearers needed bags, Fortuny obliged his clients and constructed handbags from his own multicolored velvet in very simple designs.

In 1909 Fortuny opened his own salon on rue Marignan selling not only his pleated silk and velvet gowns, but also cushion covers, wall hangings, lampshades, etc. In 1912, he showed his textiles in the Spanish pavilion at the International Exhibition of Decorative Arts in Paris. In the years preceding WWI, Fortuny moved from strength to strength, and his fashions retained preeminence well into the 1920s, whereas his pre-War contemporaries—Poiret, Doucet, Callot Soeurs—faltered and failed with the rise of designers like Gabrielle Chanel.

Today, Mariano Fortuny is remembered as a Renaissance man for his versatile mosaic of talents, but particularly for his mastery in his textiles and garments. Though the secret pleat-setting process used by Fortuny is little understood to this day, this website details the process of faking Fortuny’s famous pleats.

Sources: 1, 2, 3

Further Reading:

Fortuny by Anne-Marie Deschodt

Mariano Fortuny, His Life and Work by Guillermo De Osma

I tried to visit the Fortuny museum when I was in Venice but it was closed. I love Fortuny and Mary MacFadden wouldn’t have a career as a designer if it weren’t for him.

Is there a pattern for the delphos dress? Thank you for your Mariano Fortuny article!

Hi Catherine,

Thanks for stopping by! I don’t think there are any patterns, but here is the link I provided at the end of the article, where a costume designer recreated the Delphos Gown: Faking Fortuny’s Pleats.