The Cakewalk had its origins in slavery. Peering through the windows at the spectacles hosted by white planters, enslaved blacks would then prance and preen in imitation of whites at their own dances, using exaggerated movements, curtsys and bows to and adopting “high-toned” clothing to mock. In performance, couples would line up to form an aisle, down which each pair would take a turn at a high-stepping promenade through the others. The irony was extended when white planters began to host and judge Cakewalk competitions, awarding a cake of some kind to the winning couple.

The meaning of the dance was lost on white minstrel performers, who added the exaggerated, over-the-top dance to their repertoire to portray the bumbling attempts of poor blacks to mimic the manners of whites. No longer was the Cakewalk a dance of satire; minstrels and their audience genuinely thought it signified blacks wanting to be like whites. By the turn of the century, the Cakewalk was used by both black and white minstrel performers far from its original intentions, and when the musical comedy gained prominence in theatre, the Cakewalk was transferred from the circuit theatre to Broadway.

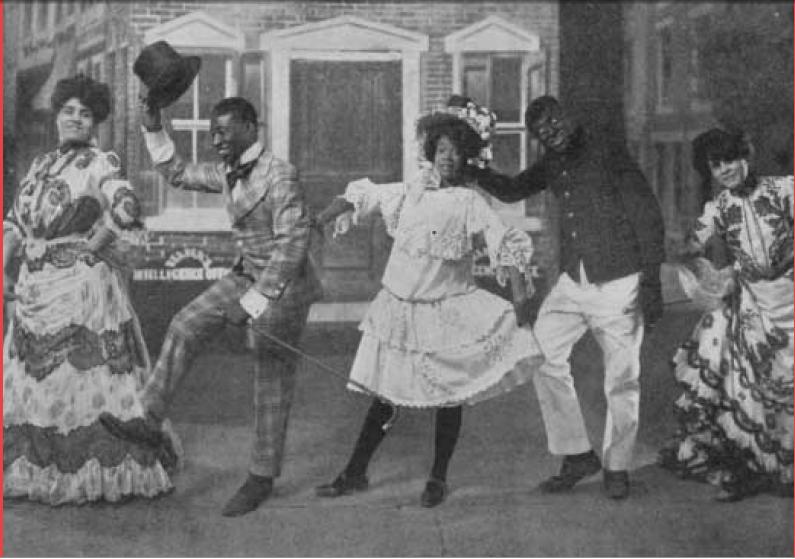

Dora Dean and her husband Charles E. Johnson brought the dance to the Great White Way in the 1893 production of The Creole Show. Their performance was a sensation. Not only did Dean, Johnson and the entirely black cast dispense with blackface, but the partner dancing on stage was a novelty. This success was followed by the musical comedy Clorindy The Origin of the Cakewalk (1898), an hour-long sketch that was the first all-black show to play in a prestigious Broadway house, Casino Theatre’s Roof Garden, whose ragtime music was scored by Will Marion Cook and whose cast of black dancers and white act

Dora Dean and her husband Charles E. Johnson brought the dance to the Great White Way in the 1893 production of The Creole Show. Their performance was a sensation. Not only did Dean, Johnson and the entirely black cast dispense with blackface, but the partner dancing on stage was a novelty. This success was followed by the musical comedy Clorindy The Origin of the Cakewalk (1898), an hour-long sketch that was the first all-black show to play in a prestigious Broadway house, Casino Theatre’s Roof Garden, whose ragtime music was scored by Will Marion Cook and whose cast of black dancers and white act ors became the first instance of integration on stage in New York. The comedy also introduced the actors most associated with the dance, George Walker and Bert Williams.

ors became the first instance of integration on stage in New York. The comedy also introduced the actors most associated with the dance, George Walker and Bert Williams.

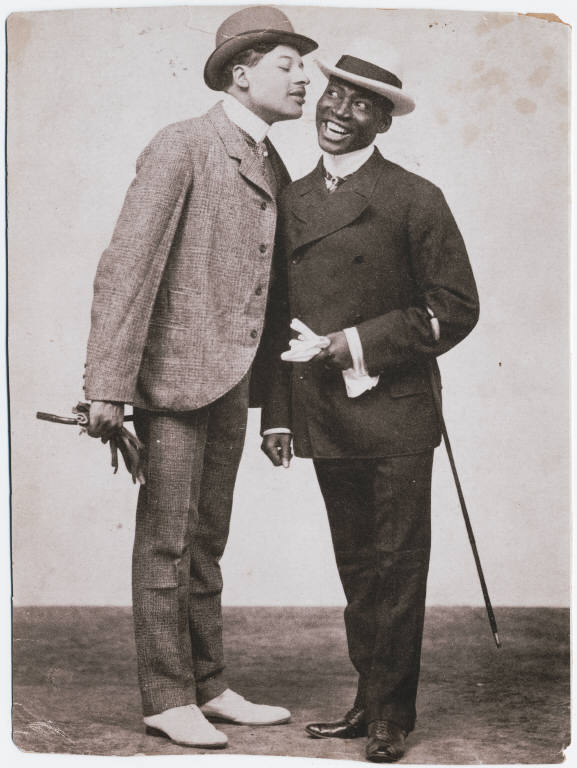

Walker and Williams teamed up in the early 1890s after meeting in San Francisco. They performed the typical song-and-dance numbers, comic dialogues, skits and humorous songs of the vaudeville oeuvre, but found fame when they discovered, after portraying the stereotypical vaudevillian roles of con-man and victim (Williams and Walker, respectively), that they got a better reaction by switching roles. The slender Walker eventually developed a persona as a strutting dandy, while the stocky Williams played the languorous oaf. Their performance in the musical farce The Gold Bug electrified audiences when the duo’s performance of the cakewalk so captured the audience’s attention, they soon became so closely associated with this dance that many people still think of them as its originators.

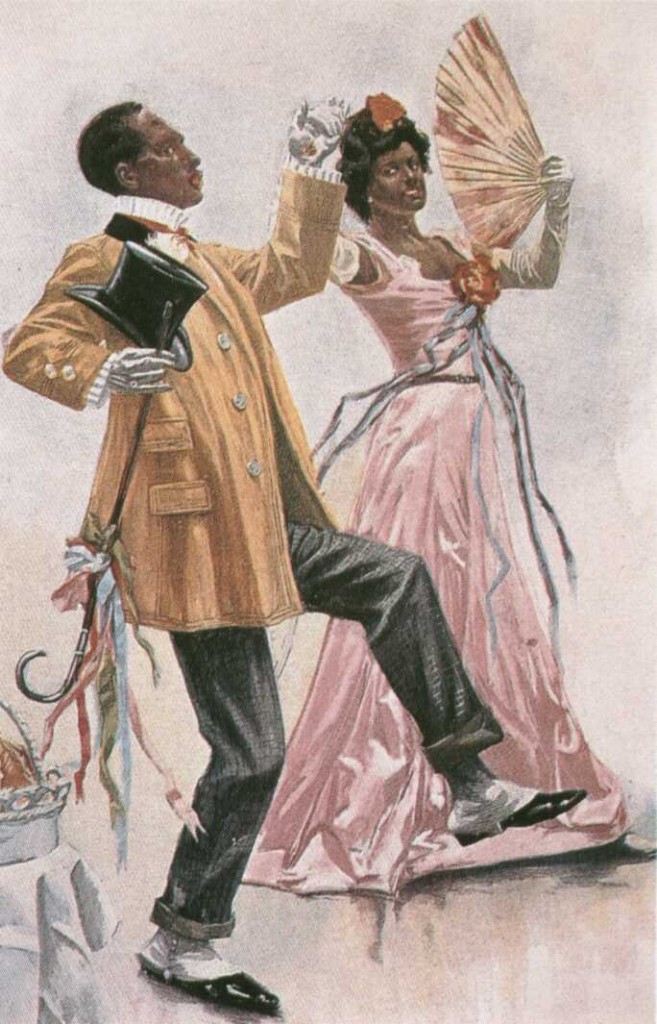

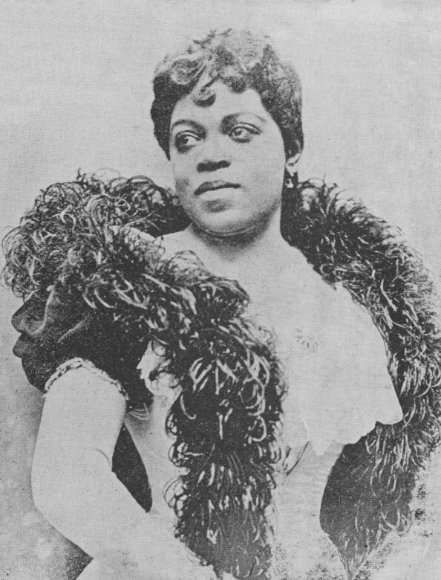

This success was followed by a booking at Koster and Bial’s Music Hall in New York. Playing this well-known venue was a step up for them, and many doors opened as a result. Joining them was Walker’s wife, Ada (or Aida) Overton, whom George met in 1898 after they posed for a cigarette advertisement. They married the following year and she became the leading lady and soubrette in the Williams and Walker Company, soon after becoming famous in her own right as a performer of the Cakewalk.

She dazzled early-twentieth-century theater audiences with her original dance routines, her enchanting singing voice, and her penchant for elegant costumes. Her interpretation of the Cakewalk was to rewrite the bodily gestures of the dance in ways that appealed to white elites and black Americans, and make the dance “respectable.” Her elegant cakewalking opened the door for the Four Hundred to pick up the dance and Ada was hired frequently by New York’s renowned hostesses to teach guests how to Cakewalk at fancy balls and tableaux.

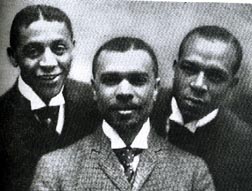

This success was fine, but the ultimate goal the Williams and Walker Company of was to produce and star in their own Broadway musical. From their original meeting, the men wanted to introduce African themes on Broadway and rid the theatre of the limitations placed on black actors. In 1902, the duo teamed with Will Marion Cook, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, and Jesse Shipp to produce In Dahomey, the first musical to open on Broadway written and performed entirely by African-Americans.

This success was fine, but the ultimate goal the Williams and Walker Company of was to produce and star in their own Broadway musical. From their original meeting, the men wanted to introduce African themes on Broadway and rid the theatre of the limitations placed on black actors. In 1902, the duo teamed with Will Marion Cook, Paul Lawrence Dunbar, and Jesse Shipp to produce In Dahomey, the first musical to open on Broadway written and performed entirely by African-Americans.

The musical was a resounding smash hit, and the company took In Dahomey to England the following year. Initially met with tepid response, the play picked up after the Royal Family requested a special performance at Buckingham Palace, where King Edward sent a courtier to inquire whether the cakewalk just performed was the most absolute form of the dance, and of course, the company said it was. In Dahomey ran for four years, and broke all records: it helped make its composer, lyricist and leading performers house-hold names, and its score was the first black musical that had its score published (in England, not America).

The musical was a resounding smash hit, and the company took In Dahomey to England the following year. Initially met with tepid response, the play picked up after the Royal Family requested a special performance at Buckingham Palace, where King Edward sent a courtier to inquire whether the cakewalk just performed was the most absolute form of the dance, and of course, the company said it was. In Dahomey ran for four years, and broke all records: it helped make its composer, lyricist and leading performers house-hold names, and its score was the first black musical that had its score published (in England, not America).

The Cakewalk became the first black dance to be accepted by white society, which paved the way for the acceptance of other dances of African-American origin, such as the turkey trot or bunny hug, and later, the Black Bottom, the Charleston, all the way to the Electric Slide. As for the Walkers and Bert Williams, the trio continued their success despite George dying of syphilis in 1908, and Ada succumbing to kidney failure in 1914. Bert Williams continued as a solo artist, become a star performer with Ziegfeld’s Follies, and recording songs to much acclaim. He died in 1922. Despite their early deaths, George and Ada Walker, and Bert Williams proved the talent and dedication of black actors, and their successes pushed a recalcitrant Broadway (and society) to accept the presence of a black performer, or a black star, on the stage.

The Cakewalk became the first black dance to be accepted by white society, which paved the way for the acceptance of other dances of African-American origin, such as the turkey trot or bunny hug, and later, the Black Bottom, the Charleston, all the way to the Electric Slide. As for the Walkers and Bert Williams, the trio continued their success despite George dying of syphilis in 1908, and Ada succumbing to kidney failure in 1914. Bert Williams continued as a solo artist, become a star performer with Ziegfeld’s Follies, and recording songs to much acclaim. He died in 1922. Despite their early deaths, George and Ada Walker, and Bert Williams proved the talent and dedication of black actors, and their successes pushed a recalcitrant Broadway (and society) to accept the presence of a black performer, or a black star, on the stage.

Further Reading:

Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance by Marshall Winslow Stearns & Jean Stearns

Staging Race: Black Performers in Turn of the Century America by Karen Sotiropoulos

A History of African American Theatre by Errol Hill & James Vernon Hatch

Swing Along: The Musical Life of Will Marion Cook by Marva Carter

The Cambridge Companion to African American Theatre by Harvey Young

Cross the Water Blues: African American Music in Europe by Neil A. Wynn

Introducing Bert Williams: Burnt Cork, Broadway, and the Story of America’s First Black Star by Camille Forbes

This is an excellent and educational article. Thanks for sharing it.

Thanks for the article. I would like to know if there are Cake Walk and Two Steps classes in NYC.

Thanks.

Marie

Hi Marie, you should search the web to see if there are any historical dance societies in your area. I can’t guarantee they’ll have Ragtime dances (most tend to focus on the social dances like the waltz, the polonaise, the cotillion, etc), but Dancetime Publications does have a video series that teaches historical dances through time. Here’s their Ragtime Era video.