Decadence was the word frequently used to describe fin de siècle Europe. Boulangism, the Panama Scandal, the Dreyfus Affair and the anarchist bombings shattered the complaisance of 1890s France, while the trial of Oscar Wilde, the Royal Baccarat Scandal and the continued tug-of-war over Home Rule between the Conservatives and the Liberals, combined with a distressing agricultural slump left over from the 1880s, plagued the shores of Great Britain. Society was desperate for escape, and when the stunning new technological advances and the penny presses failed to divert attention away from social ills, many turned to drugs and alcohol.

The 1870s had seen an increase in the use of drugs as they became more available, and though chloral (prescribed to combat insomnia after 1869) and barbiturates such as veronal or gardenal were popular, the great favorite of the epoch was opium, and its derivative, morphine. Opium was used in therapy as a sedative, a cure for insomnia and a solution to various pains and aches, for dysentery and for diarrhea. Laudanum, the alcoholic tincture of opium, could be purchased at the drug store and prepared at home to remedy the same symptoms, while the practice of smoking opium was introduced by naval officers returning from the colonies in the 1840s and 1850s. However, it wasn’t until morphine was introduced to the market that society took to a drug habit.

“Morphine,” said Dumas fils, “is the absinthe of women.” So prevalent was the habit amongst upper-crust ladies of the highest circles, in 1902 the British Medical Journal expressed dismay over the existence of morphine tea parties:

“Morphine,” said Dumas fils, “is the absinthe of women.” So prevalent was the habit amongst upper-crust ladies of the highest circles, in 1902 the British Medical Journal expressed dismay over the existence of morphine tea parties:

which is said to have originated in Paris, [and] consists of the formation of what may be termed a morphine club. A number of ladies meet about 4 O’clock every afternoon, tea is served, servants are sent out of the room, the door is locked, the guests bare their arms, and the hostess produces a small hypodermic syringe with which she administers an injection to each person in turn. If one injection is not sufficient to satisfy any particular guest, a second or even a third is given.

To satisfy this trend, jewelers did a brisk trade in silver-gilt or gold-plated syringes, but by the early half of the 1890s, addiction had become a plague, and many well-known socialites ended their lives “a bit morphinomane“–ostensibly to calm their stomachs.

Many others retained the old-fashioned habit of hashish, while the use of ether, introduced by Guy de Maupassant, nearly replaced morphine, some consuming ether-soaked strawberries and others swilling as much as half a liter a day between swallows of water, or taken with brandy, when the ordinary dose was but five to six grams!

When cocaine was introduced in the 1880s, it caught on almost at once. Though the South American cocoa plant was brought to Europe in the 16th century, cocaine was not chemically isolated until 1844. Commercial manufacture of the plant began in 1862, and its medicinal propertieswere discussed in 1883 when a Bavarian army doctor uncovered its usefulness as an anti-fatigue agent. The following year, it began to be used as a local anesthetic in ophthalmology and dentistry, but it was Sigmund Freud who defended the “wonder drug” in the face of cautions in medical journals, praising it and prescribing it for a variety of ailments, ranging from sea-sickness to melancholia to ironically, rehabilitating morphine addicts.

When cocaine was introduced in the 1880s, it caught on almost at once. Though the South American cocoa plant was brought to Europe in the 16th century, cocaine was not chemically isolated until 1844. Commercial manufacture of the plant began in 1862, and its medicinal propertieswere discussed in 1883 when a Bavarian army doctor uncovered its usefulness as an anti-fatigue agent. The following year, it began to be used as a local anesthetic in ophthalmology and dentistry, but it was Sigmund Freud who defended the “wonder drug” in the face of cautions in medical journals, praising it and prescribing it for a variety of ailments, ranging from sea-sickness to melancholia to ironically, rehabilitating morphine addicts.

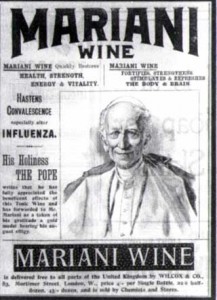

For its stimulating properties, cocaine was consumed in the guise of Vin Mariani, a medicinal wine containing an infusion of coca leaves (endorsed by no less than Pope Leo XIII!), or, in the United States, Coca-Cola, which was conceived in 1886 by an Atlanta-based cough syrup manufacturer hoping to cash in on the coca-beverage market. Medicinally, cocaine was taken either orally, or subcutaneously via hypodermic needle.

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, cocaine remained unrestricted by law or custom. It was available in an extraordinary number of forms–snuff, candy, coca-leaf cigarettes, ointments, pills, gargles, “chewing pastes,” and even suppositories–by anyone with enough money to purchase the items. Even fictional characters like Sherlock Holmes indulged in the practice (though Dr. Watson rightly disapproved). While there was some social stigma attached to drug addiction, it never occurred to 19th century legislatures to create laws against drug use to restrict the burgeoning pharmaceuticals industry. However, it was the use of cocaine more than any other factor that brought about public outcry against drug addiction. The morphine or opium addict was able to live a relatively normal life as long as their access to the drug was unhampered, but cocaine, with its capacity to create bizarre behavior patterns, caused society to focus on the side effects of drug use.

Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, cocaine remained unrestricted by law or custom. It was available in an extraordinary number of forms–snuff, candy, coca-leaf cigarettes, ointments, pills, gargles, “chewing pastes,” and even suppositories–by anyone with enough money to purchase the items. Even fictional characters like Sherlock Holmes indulged in the practice (though Dr. Watson rightly disapproved). While there was some social stigma attached to drug addiction, it never occurred to 19th century legislatures to create laws against drug use to restrict the burgeoning pharmaceuticals industry. However, it was the use of cocaine more than any other factor that brought about public outcry against drug addiction. The morphine or opium addict was able to live a relatively normal life as long as their access to the drug was unhampered, but cocaine, with its capacity to create bizarre behavior patterns, caused society to focus on the side effects of drug use.

By the 1910s, nearly all Western nations passed laws to regulate the drug trade and the manufacture of patent medicines, and restricting cocaine, morphine, and opium, among others, to a doctor’s prescription.

Further Reading:

Subcutaneously, My Dear Watson by Jack Tracy and Jim Berkey

France, Fin de Siècle by Eugen Weber

nice story,unfortunatelly,nowadays people can find cocaine everywhere

Very interesting post. I knew that Coca-Cola originally had had coke in it but I had no idea that they were mixing it into candy!

I always find it très amusant that one hundred years+ ago, things we know to be terrible were just new products to try.

Great post! Also to be noted is the use and abuse of laudanum, an opium and alcohol mix.