There is no other expression of American democracy than the exit of one President for another. Whether the President has served one term or two–or in the case of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, four–the inauguration ceremony is one of excitement, triumph and the bittersweet. The first inauguration was held on April 30, 1789, in New York City. The day was originally set for March 4, which gave electors from each state just about four months after Election Day to cast their ballots for president. This was changed in 1937 by the 20th Amendment, which changed Inauguration Day to noon on January 20, in time for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s second term. Thomas Jefferson became the first president to be sworn in at our nation’s capital, though D.C. did not official become the federal capital until 1801.

There is no other expression of American democracy than the exit of one President for another. Whether the President has served one term or two–or in the case of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, four–the inauguration ceremony is one of excitement, triumph and the bittersweet. The first inauguration was held on April 30, 1789, in New York City. The day was originally set for March 4, which gave electors from each state just about four months after Election Day to cast their ballots for president. This was changed in 1937 by the 20th Amendment, which changed Inauguration Day to noon on January 20, in time for Franklin D. Roosevelt’s second term. Thomas Jefferson became the first president to be sworn in at our nation’s capital, though D.C. did not official become the federal capital until 1801.

All inaugural ceremonies at the Capitol have been organized by the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies since 1901, and the U.S. military has participated in Inauguration Day ceremonies from the first president, as the president is commander-in-chief of the armed forces. Naturally, the proceedings for the inauguration of a new or continuing president were strictly regulated by etiquette.

It was customary for the President-elect to arrive in the city one or two days before the time designated for his formal induction into office. Upon the arrival of the President-elect at the Capital the national colors would be floated from all public buildings during each day between sunrise and sunset until after the inaugural ceremonies. As soon as practicable after his arrival the President-elect would call upon the President, having previously sent a messenger to ascertain his convenience as to time, to pay his respects and to exchange views with reference to the ceremonies attendant upon his succession and taking possession of the Executive office. The President returned the call of the President-elect on the same day. The President then invited the President-elect and members of his Cabinet and ladies to dinner before the expiration of his term of office. He also held a levee at a convenient time before his retirement.

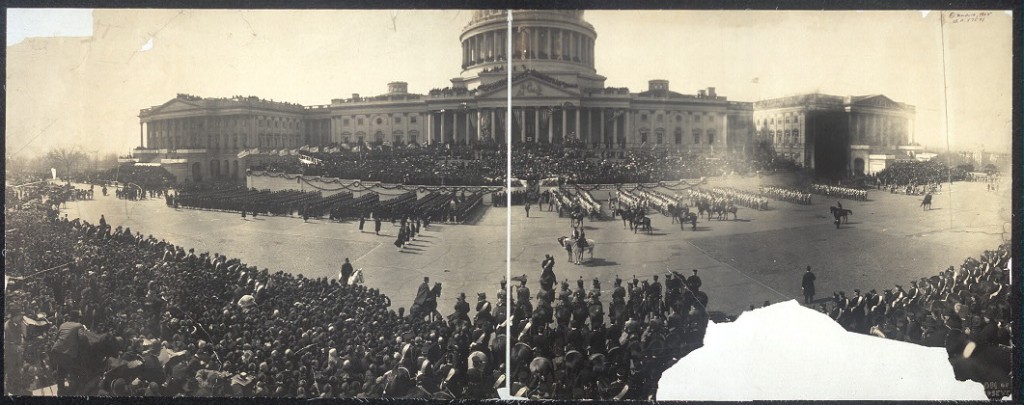

The inauguration of the President was attended by more or less pomp. The order of arrangements for the inaugural procession was assigned to a military officer. The following is the official program adopted and promulgated for the inaugural ceremonies of March 4, 1881, from which point it was free to elaborate upon:

The inauguration of the President was attended by more or less pomp. The order of arrangements for the inaugural procession was assigned to a military officer. The following is the official program adopted and promulgated for the inaugural ceremonies of March 4, 1881, from which point it was free to elaborate upon:

Two platoons of City Police (mounted)

Grand Marshal and Aids

First Division: Chief Officers, Aids, U.S. Artillery, Marine Battalion, Troops (if any) which accompany the President-elect to the seat of Government; The President and President-elect and party in carriages, attended by three aids; Calvary, Portion of the visiting military organizations

Second Division: the Chief Officer and Staff, Visiting Military designated

Third Division: the Chief Officer, Staff, Grand Army of the Republic, Misc military organizations from different states

Fourth Division: the Chief Officer, Staff, Misc military organizations

Fifth Division: the CO, Staff or Aids, Civic Societies, Political Organizations, Fire Department, etc

Salutes: The artillery will post a gun and detachment in the mall south of the Treasury, and another in the Capitol grounds to fire the signal guns when so required

The procession moved towards the Capitol at 10:15 am. At that hour, Pennsylvania Ave would be cleared of vehicles.

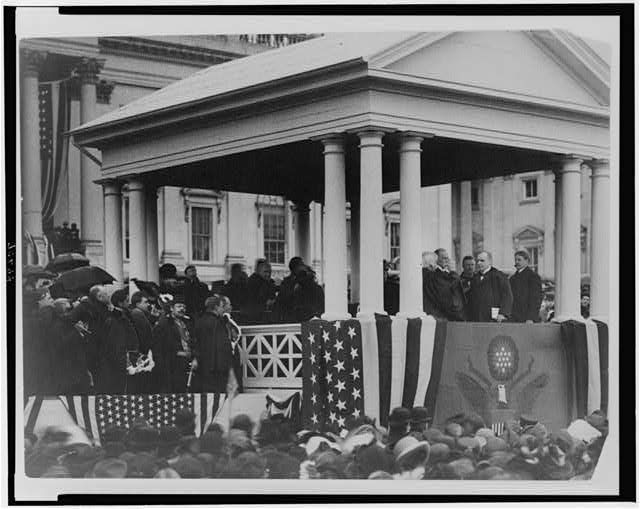

After arriving at the Capitol, the President and President-elect were escorted to the Senate Chamber, while the troops and civic organizations massed in front of the building. The ceremonies attending the administration of the oath of office to the President-elect were under the direction of the Senate. After the conclusion of the inauguration ceremony in the Senate, the President was conducted to his carriage and attended by the guard of honor, who drove him to the reviewing stand erected for the purpose on Pennsylvania Ave north of the White House. If the new President chose to take immediate possession of the White House, the retired President and his First Lady awaited his arrival there to welcome him into the mansion, and formally yielded up its possession. A lunch was usually prepared by the direction of the retired President, at which the new President presides. After this, the retired President and the First Lady withdrew from the mansion to their temporary residence in the city.

After arriving at the Capitol, the President and President-elect were escorted to the Senate Chamber, while the troops and civic organizations massed in front of the building. The ceremonies attending the administration of the oath of office to the President-elect were under the direction of the Senate. After the conclusion of the inauguration ceremony in the Senate, the President was conducted to his carriage and attended by the guard of honor, who drove him to the reviewing stand erected for the purpose on Pennsylvania Ave north of the White House. If the new President chose to take immediate possession of the White House, the retired President and his First Lady awaited his arrival there to welcome him into the mansion, and formally yielded up its possession. A lunch was usually prepared by the direction of the retired President, at which the new President presides. After this, the retired President and the First Lady withdrew from the mansion to their temporary residence in the city.

President Washington set the precedent for retiring from the Presidential office, when he published a farewell address, reviewing some of features of his administration. It then became customary for the retiring President to review principal acts of his administration in his last annual message to Congress, preceding the expiration of his term of office. His departure from the Capital was attended with no ceremony, other than the members of his late Cabinet and a few officials and personal friends. The President left the Capital as soon as practical after the inauguration.

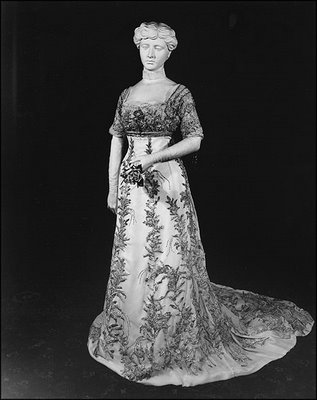

The excitement of the day didn’t end there. It was customary to close the ceremonies of Inauguration with a grand ball, which was generally conducted under the auspices of a citizens committee of arrangements, appointed at a public meeting. Arousing much comment and curiosity was the costliness of the ball and more importantly, what the new First Lady was to wear. Mrs. McKinley dazzled with a gown made of silver cloth. The groundwork was of white satin, heavily woven with silver thread in a lily design. The full, sweeping train was plain, but measured two and a half yards in length. The left side was open over a panel of seed pearls, embroidered on satin, and at the bottom, a flounce of Venetian point lace cascaded, partially concealed beneath the train. The right side of the skirt was also slashed open half way up and under that was also am embroidered petticoat of pearls. Special silk was woven for Mrs Roosevelt’s inaugural gown, and it was shipped from New Jersey to Washington days before March 4. Of heavy brocade, with a background of blue, through which, at intervals, was woven the figure of a dove. The filling was of gold tinsel. Appropriately, given the occasion and the wearer, the pattern was destroyed, allowing Edith Roosevelt a one-of-a-kind ballgown. 1909 saw Mrs. Helen Taft in “one of the handsomest models ever seen in Washington.” A severely plain underdress of heavy white satin formed the foundation. Over this was draped with white chiffon, on which a pattern of goldenrod, the National flower, was embroidered in silver. The design was repeated in the embroidery of the long Court train, and point lace formed the sleeves and served to trim the decolletage. In her hair was a diamond aigrette, and around her neck, a pearl dog collar.

The excitement of the day didn’t end there. It was customary to close the ceremonies of Inauguration with a grand ball, which was generally conducted under the auspices of a citizens committee of arrangements, appointed at a public meeting. Arousing much comment and curiosity was the costliness of the ball and more importantly, what the new First Lady was to wear. Mrs. McKinley dazzled with a gown made of silver cloth. The groundwork was of white satin, heavily woven with silver thread in a lily design. The full, sweeping train was plain, but measured two and a half yards in length. The left side was open over a panel of seed pearls, embroidered on satin, and at the bottom, a flounce of Venetian point lace cascaded, partially concealed beneath the train. The right side of the skirt was also slashed open half way up and under that was also am embroidered petticoat of pearls. Special silk was woven for Mrs Roosevelt’s inaugural gown, and it was shipped from New Jersey to Washington days before March 4. Of heavy brocade, with a background of blue, through which, at intervals, was woven the figure of a dove. The filling was of gold tinsel. Appropriately, given the occasion and the wearer, the pattern was destroyed, allowing Edith Roosevelt a one-of-a-kind ballgown. 1909 saw Mrs. Helen Taft in “one of the handsomest models ever seen in Washington.” A severely plain underdress of heavy white satin formed the foundation. Over this was draped with white chiffon, on which a pattern of goldenrod, the National flower, was embroidered in silver. The design was repeated in the embroidery of the long Court train, and point lace formed the sleeves and served to trim the decolletage. In her hair was a diamond aigrette, and around her neck, a pearl dog collar.

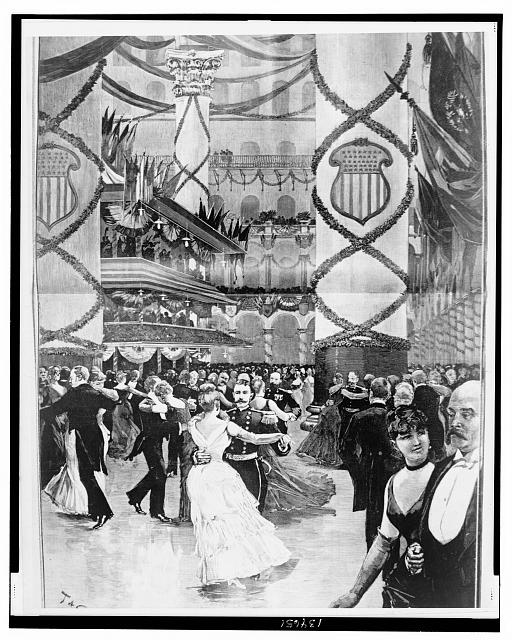

The inaugural ball was considered by many the quadrennial tribute paid by politics to society. There had only been but two intermission in the series of inaugural balls to commemorate the accession of a newly-elected President. The earlier balls were held on sites then deemed fashionable. Martin Van Buren had two balls given in his honor, William Henry Harrison gave three, James K. Polk had two, one of which was charged $10 a ticket and the other $2, Zachary Taylor had three balls given in his honor, and President Pierce would up being inaugurated in a snowstorm, and had no ball given him. By the 1880s, the Pension Building was staked as the official ballroom for the inauguration ball. Tickets to President Cleveland’s ball cost $5 apiece, and fully 12,000 guests were provided for in the committees plans. The ball was catered to meet vigorous appetites: over 60,000 oysters, 10,000 chicken croquettes, 7,000 sandwiches, 150 gallons of lobster salad, 300 gallons of stewed terrapin, 150 boned turkeys, 300 gallons of chicken salad, 1,300 quarts of ice cream and hundreds of pounds of pate de foie gras.

The inaugural ball was considered by many the quadrennial tribute paid by politics to society. There had only been but two intermission in the series of inaugural balls to commemorate the accession of a newly-elected President. The earlier balls were held on sites then deemed fashionable. Martin Van Buren had two balls given in his honor, William Henry Harrison gave three, James K. Polk had two, one of which was charged $10 a ticket and the other $2, Zachary Taylor had three balls given in his honor, and President Pierce would up being inaugurated in a snowstorm, and had no ball given him. By the 1880s, the Pension Building was staked as the official ballroom for the inauguration ball. Tickets to President Cleveland’s ball cost $5 apiece, and fully 12,000 guests were provided for in the committees plans. The ball was catered to meet vigorous appetites: over 60,000 oysters, 10,000 chicken croquettes, 7,000 sandwiches, 150 gallons of lobster salad, 300 gallons of stewed terrapin, 150 boned turkeys, 300 gallons of chicken salad, 1,300 quarts of ice cream and hundreds of pounds of pate de foie gras.

With all this hustle and bustle, one can imagine the sentiments of the day when President Woodrow Wilson canceled plans for an inaugural ball in 1913. In the midst of societal outrage, the milliners, caterers, dressmakers, tailors, chauffeurs, and any other person who provided services and goods for ball attendees were devastated. The New York Times reported a glut of white gloves on the market, citing their obscenely cheap prices as a result of glovers overstocking their wares in anticipation of the inauguration. After the frenzy died down, it was revealed that President Wilson canceled the ball fearing the dancing of the turkey trot! He instead opted for a safe, turkey-trot-free reception.

Read the Inaugural Addresses of America’s Presidents from George Washington to George W. Bush

Watch:

The Inauguration of President McKinley, 1897

President McKinley’s Second Inauguration, 1901

President Roosevelt’s Inauguration, 1905

First Lady Fashion: 200 Years

Photographs courtesy of Library of Congress

More photos of First Lady inaugural gowns: Past Perfect