When stationed abroad–or sent away for some nefarious reason or other–the English imported the manners and mores of Home to their new locale. As the British Empire grew, spreading across Asia, Africa and Down Under, it was imperative to maintain ‘civilization’ and ‘culture’ in the midst of ‘brutish’ nations. Though the leading official of Britain’s colonies, and later, commonwealths, were referred to as “Viceroys,” their accurate title was that of either Governor-General or Lord Lieutenant. Of the Viceroyalty, India, that jewel in the crown of the Empire, was the most coveted position.

When stationed abroad–or sent away for some nefarious reason or other–the English imported the manners and mores of Home to their new locale. As the British Empire grew, spreading across Asia, Africa and Down Under, it was imperative to maintain ‘civilization’ and ‘culture’ in the midst of ‘brutish’ nations. Though the leading official of Britain’s colonies, and later, commonwealths, were referred to as “Viceroys,” their accurate title was that of either Governor-General or Lord Lieutenant. Of the Viceroyalty, India, that jewel in the crown of the Empire, was the most coveted position.

In these territories, society revolved around the Government House. Though an invitation to Government House was considered no more exclusive than attending a Court ball in London, it was coveted as a symbol of at least hovering on the fringes of society. In Melbourne, Australia, the scattered position of the suburbs created a number of elite circles, but there remained but one creme de la creme–and in Sydney, the same thing occurred. However in Adelaide, there was but one society, and they were considered the most English and exclusive. However exclusive these circles may be, class was a fluid concept because of the skewed ration of men versus women. Australian writers describing their country bemoaned the frequency of mesalliances, and detailed stories abounded of being invited to dine at the home of a cultured man and discovering the man’s wife dropped her h’s and ate her peas with a knife. Richard Twopeny, in his book “Town Life in Australia” noted that the rule of Australian society was to avoid asking questions about or making reference to the early days of a colonist–it was likely that a society leader and her husband were formerly a scullery maid and shop-keeper, respectively.

This melding of various classes and socio-economic backgrounds led to a startling informality. The man-about-town would dress down rather than up for his Sunday stroll (a top hat, gloves and waistcoat would bring jeers), and the dearth of servants–for people emigrated to start anew!–induced many Australian ladies to pitch in and clean their homes and cook themselves.

This melding of various classes and socio-economic backgrounds led to a startling informality. The man-about-town would dress down rather than up for his Sunday stroll (a top hat, gloves and waistcoat would bring jeers), and the dearth of servants–for people emigrated to start anew!–induced many Australian ladies to pitch in and clean their homes and cook themselves.

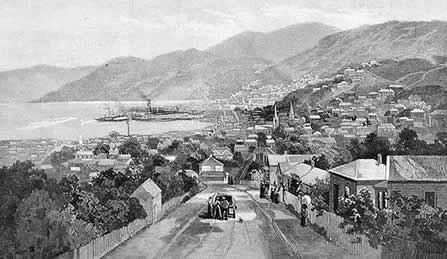

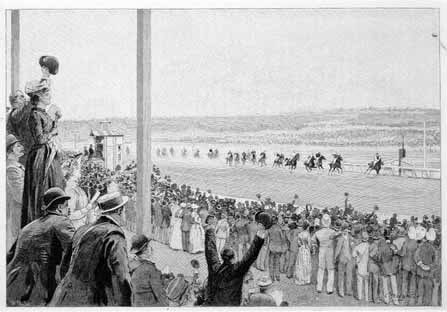

New Zealand society was just as informal, if not more so. They had their Government House in Wellington, and to receive an invitation to a ball, one had only to sign their name to the Visitor’s Book and await the square of pasteboard to arrive. New Zealand ladies thought nothing of setting out to pay formal calls on foot–though with a pistol handy in case of emergency. Because of the great distances between settlers and cities, social gatherings went on for days: one dance lasted for a day, a night, and another night. Of other amusements and entertainments, the opera was very popular, and there was a mania for gambling. Not surprisingly, long after the fad for rinking (roller skating) was introduced to England and America, it became a craze in Australia, and it was noted that there was no set hour for the fashionable to use the rinking rings; a maid could sail past her employer and even link arms with the daughter of the house. Sports were a given past-time, with pony races and dingo hunts indulged in by the men.

The delightful informality of society in New Zealand and Australia ended there. Society in places like India, Hong Kong and Shanghai centered around Government House, but the presence of the military in other British colonies and dominions reinforced English social patterns–though the elite of Hong Kong and Shanghai society were more likely to derive from the merchant classes.

The delightful informality of society in New Zealand and Australia ended there. Society in places like India, Hong Kong and Shanghai centered around Government House, but the presence of the military in other British colonies and dominions reinforced English social patterns–though the elite of Hong Kong and Shanghai society were more likely to derive from the merchant classes.

The seasons–cold, hot or wet–dictated the pattern of British society in India, and the club did the rest. Every center except the smallest had a club, whether it be called a club or were actually a polo or gymkhana club, and joining it was the most important step in becoming accepted in that area’s society. The cold season, lasting from November to April, was marked by the arrival of the “fishing fleet”–the collective name given to girls with family connections in India who came out to snare a husband. Christmas, with pea fowl rather than turkey, and presents ordered from Home in October, was the climax of this portion of the season, and after that, the Viceroy’s Ball at Delhi carried he message that the hot weather, with its temperatures of 130 degrees in the shade, would shortly begin. Society decamped to hill stations like Simla (Shimla), Musoori (Mussoorie) and Darjeeling to escape the heat, and left the men behind to their employment and masculine pursuits. The hills were very much the woman’s world, and was organized along the lines of the London season. This “hot” season ended in October, when the memsahibs and their families once more returned to the Plains for the “cold” season.

Society in Hong Kong and Shanghai was unlike any other. Here, merchants ruled supreme, though to outsiders, the hierarchy was extremely puzzling: why should Mrs. X whose spouse exports tea be “haut ton,” while Mrs. Y whose husband imports cigars is not to be called on? A further source of surprise was that officers in the Indian Army were not considered eligible dancing partners for the daughters of the Hong Kong elite. The firm of Jardine Matheson was the “Princely Hong” since the founder, William Jardine, a ship’s surgeon, could claim to have “discovered” the island of Hong Kong. A Crown Colony ruled by a Governor-General and a Council, society was less formal than India, though not as informal as Down Under. Because of its position as a major port, the British mingled with a bevy of nationalities and occasionally the very wealthy Chinese. However, the stench of opium trading hung over both Hong Kong and Shanghai, lending the two trading ports a sinister air.

Society in Hong Kong and Shanghai was unlike any other. Here, merchants ruled supreme, though to outsiders, the hierarchy was extremely puzzling: why should Mrs. X whose spouse exports tea be “haut ton,” while Mrs. Y whose husband imports cigars is not to be called on? A further source of surprise was that officers in the Indian Army were not considered eligible dancing partners for the daughters of the Hong Kong elite. The firm of Jardine Matheson was the “Princely Hong” since the founder, William Jardine, a ship’s surgeon, could claim to have “discovered” the island of Hong Kong. A Crown Colony ruled by a Governor-General and a Council, society was less formal than India, though not as informal as Down Under. Because of its position as a major port, the British mingled with a bevy of nationalities and occasionally the very wealthy Chinese. However, the stench of opium trading hung over both Hong Kong and Shanghai, lending the two trading ports a sinister air.

Like India, Hong Kong society was dictated by its season: for six months out of the year the island was extremely hot, and that was alleviated only by a southwest monsoon. To escape the summer heat, society built houses on the Peak–though this was little better for it was extremely wet and foggy. Fog would sometimes envelop the Peak for days and drown everything in moisture–books became moldy and dropped from their covers, shoes turned green with a single night’s experience, and clothes were so saturated with the clammy touch of the mist that they could not be worn. To combat this, every house had a drying room, where fires burned all day long, and where bed-clothes and garments were dried. Shanghai was divided into three settlements–English, French, and American–and the Chinese city of Shanghai proper was two miles distant and walled, for the Chinese were forbidden to move freely without permission. The best weather occurred between September and May, and after that, it was frequently described as “hell.” It was a bit more sophisticated and cosmopolitan than Hong Kong, influenced by the lavishness of the American element, and many considered it a rival to the best cities in Europe.

Like India, Hong Kong society was dictated by its season: for six months out of the year the island was extremely hot, and that was alleviated only by a southwest monsoon. To escape the summer heat, society built houses on the Peak–though this was little better for it was extremely wet and foggy. Fog would sometimes envelop the Peak for days and drown everything in moisture–books became moldy and dropped from their covers, shoes turned green with a single night’s experience, and clothes were so saturated with the clammy touch of the mist that they could not be worn. To combat this, every house had a drying room, where fires burned all day long, and where bed-clothes and garments were dried. Shanghai was divided into three settlements–English, French, and American–and the Chinese city of Shanghai proper was two miles distant and walled, for the Chinese were forbidden to move freely without permission. The best weather occurred between September and May, and after that, it was frequently described as “hell.” It was a bit more sophisticated and cosmopolitan than Hong Kong, influenced by the lavishness of the American element, and many considered it a rival to the best cities in Europe.

Regardless of how far away they were from England, most colonist considered that to be “Home.” After the turn of the century, colonists in places like Canada, Australia and South Africa were the settlers began to see themselves as anything other than British, and began to develop unique identities as “Canadian” or “Australian.” However, despite the strict adherence to British social customs in colonized countries, the influence went both ways, with the countries adopting certain aspects of British culture, and British culture absorbing the customs of the other country.

Regardless of how far away they were from England, most colonist considered that to be “Home.” After the turn of the century, colonists in places like Canada, Australia and South Africa were the settlers began to see themselves as anything other than British, and began to develop unique identities as “Canadian” or “Australian.” However, despite the strict adherence to British social customs in colonized countries, the influence went both ways, with the countries adopting certain aspects of British culture, and British culture absorbing the customs of the other country.

Further Reading:

Australia from a Woman’s Point of View by Jessie Ackermann

The scenery, life and manners of Australians in town and country by Percy Clarke

Australia and the Islands of the Sea by Eva Mary Crosby Kellogg & Larkin Dunton

Town Life in Australia by Richard Twopeny

The Real Australia by Alfred Buchanan

Diary of a lady’s maid: Government House in colonial Australia by Emma Southgate, Helen Vellacott

Pictures of Southern China by John Macgowan

China, the Long-lived Empire: The Long-lived Empire by Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore

Personal Reminiscences of Thirty Years’ Residence in Shanghai by Charles M. Dyce

Out in the Noonday Sun by Valerie Pakenham

Women In Great Social Positions:

- The Wife Of The Governor-general Of Australia

- The Vicereine Of India

- The Vicereine Of Ireland

- Wife Of The Governor-General Of South Africa

- The Wife Of The Governor-General Of Canada

I didn’t realise that you’d written this post, Evangeline! I love to read about Australian society in Edwardian times – unfortunately, there’s not much information about it! The heat, the long distances, and the backgrounds of people would have made it rather fraught. I must look up all of the books that you’ve mentioned.

Hi Lisa! I’d been meaning to write about society abroad, but it wasn’t until a commenter asked me about life Down Under that I sat down and wrote the post! I’ve found a few titles online (forgotten one of them), but here are two you could probably find for cheap on amazon: Ladies Didn’t: Recollections of an Edwardian Girlhood by Eugenie Mcneil by Eugenie Crawford and A Bunyip Close Behind Me : Recollections of the Nineties by Eugenie McNeil. Retold by Her Daughter, Eugenie Crawford.

Another fascinating post. Thanks for the effort you put into each and every blog post.

Thank you Marg. It’s only because of all the wonderful visitors EP receives that I can continue to deliver consistent quality.